Cobbett the Body-Snatcher, or What Happened to Thomas Paine’s Corpse

October 27, 2014 in American History, general history, History

Even before Thomas Paine had died, at least one of his “friends” had designs on acquiring his skull.

John Wesley Jarvis, an artist who was a close associate of the author of “Common Sense,” asked Paine once, in a rather morbid but friendly mood, if he would permit him to have his skull to study when he was dead, considering Jarvis had a “thing” for the study of craniology, and, being a younger man, would likely survive the American Revolution’s firebrand author. Paine replied “No, let me alone when I am dead; I should not like my bones to be disturbed.” However, Paine got only a decade of repose in the grave before his bones went rambling, and it is likely today those same remains are yet above ground, thanks to another “friend” who dug him up in the fall of 1819.

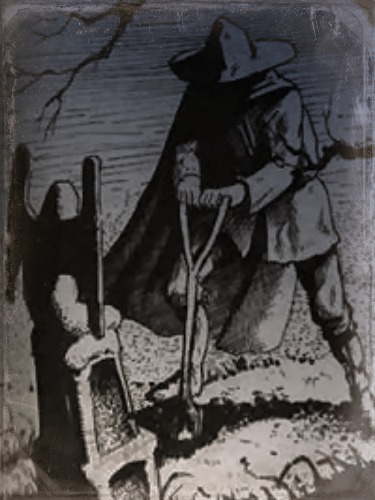

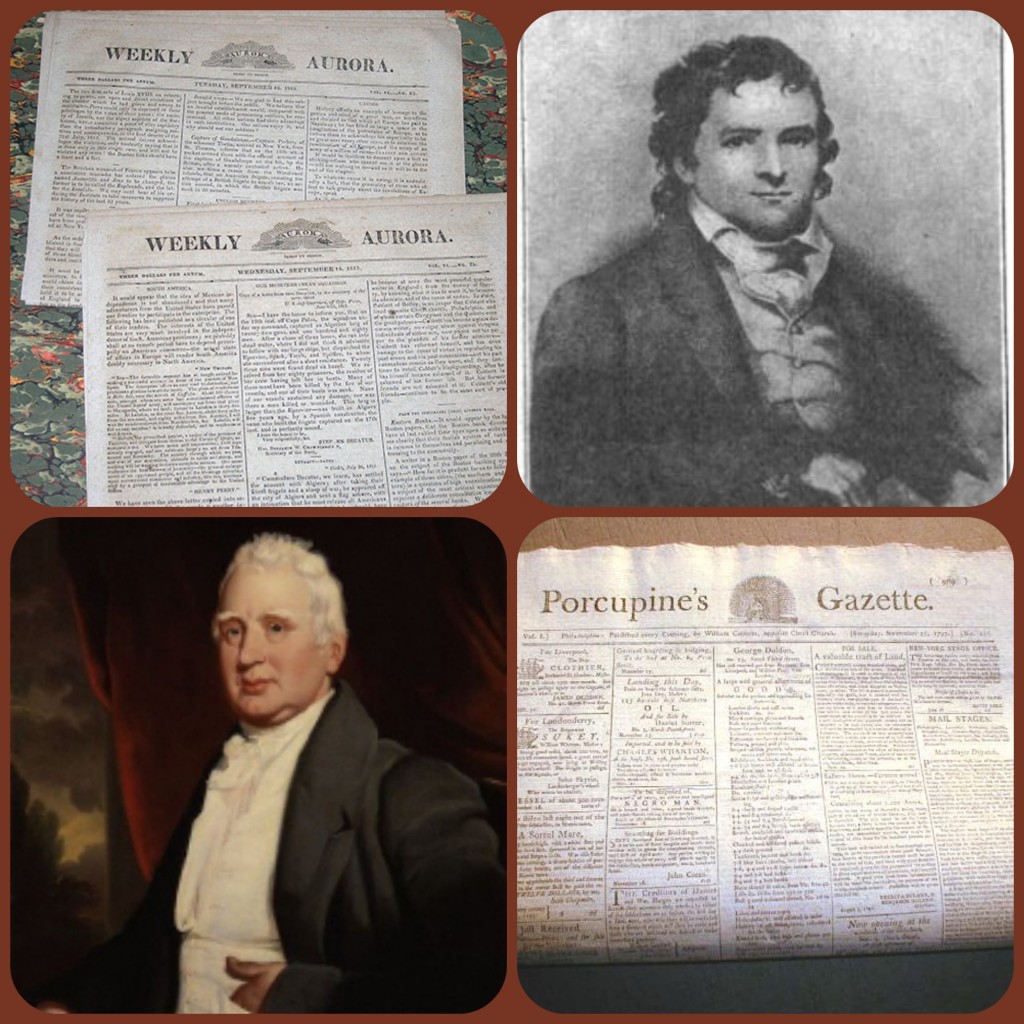

Radical newspaper editor William Cobbett, an on-again, off-again British resident of the United States, decided Paine’s forlorn final residence beneath a walnut tree on his New Rochelle, N.Y., farm was greatly ill-suited to someone he considered a fellow countryman, plus a revolutionary patriot, and all around “great man.” So the best thing to do, in Cobbett’s eyes, was to hire his printshop man Benbow plus a couple of others to head out with a covered wagon one night, and dig Paine up by lantern light so they could body-snatch the corpse and smuggle it away by ship to the country of his birth, where a suitable interment and ceremony would be held on sacred ground at St. Paul’s Church. Yet another friend of Paine’s happened to be riding by around that time, saw them in their nefarious act of grave-robbery, and alerted the local constables, but Cobbett’s men succeeded in dashing away with the coffin and mouldering contents. Cobbett, with Paine’s body packed in a probably musty-smelling large trunk, then left quickly for England by the ship Hercules as newspapers both bemoaned and applauded the act in America.

Radical newspaper editor William Cobbett, an on-again, off-again British resident of the United States, decided Paine’s forlorn final residence beneath a walnut tree on his New Rochelle, N.Y., farm was greatly ill-suited to someone he considered a fellow countryman, plus a revolutionary patriot, and all around “great man.” So the best thing to do, in Cobbett’s eyes, was to hire his printshop man Benbow plus a couple of others to head out with a covered wagon one night, and dig Paine up by lantern light so they could body-snatch the corpse and smuggle it away by ship to the country of his birth, where a suitable interment and ceremony would be held on sacred ground at St. Paul’s Church. Yet another friend of Paine’s happened to be riding by around that time, saw them in their nefarious act of grave-robbery, and alerted the local constables, but Cobbett’s men succeeded in dashing away with the coffin and mouldering contents. Cobbett, with Paine’s body packed in a probably musty-smelling large trunk, then left quickly for England by the ship Hercules as newspapers both bemoaned and applauded the act in America.

“Tom Paine has of late become literally a ‘bone of contention.’ Mr. Cobbett, it was reported, had formed a determination to ship off the rotting carcass of his fellow countryman, that it might finish the process of putrefication in the land where it germinated. Upon this, a very respectable writer observes_‘It is as it should be__let England be the sepulcher of her own blasphemy.’ The Democratic Press, and the National Advocate, take offence at such sentiments; and aver that Mr. Cobbett, if he has done the foul and ‘sacriligious’ deed, ought to be sent to the state prison,” wrote the editor of the Northern Whig of Hudson, N.Y. on Oct. 19, 1819.

The National Advocate of New York opined that they hoped the report of Paine being disinterred “is not true: we cannot bring ourselves to believe, that an act of sacrilege, so daring__so repugnant to every feeling of patriotism, has been committed by William Cobbett..remove the bones of a revolutionary patriot, from the soil which he eminently assisted in liberating, and send them to moulder in a land of slavery? What could have induced such an act? ….Whatever the errors of Paine may have been on the subject of religion, he is to be judged by a Higher Tribunal, whose rights no earthly power can usurp. As a patriot, he laboured indefatigably and successfully in achieving the Independence of America, and America is deeply indebted to him: let his errors be forgotten, and his good deeds, alone, remembered__and let no sacrilegious hand disturb his bones.”

Meanwhile, Cobbett’s “Igor” grave-robber, Benbow, sought to defend his actions at the New Rochelle farm by penning a letter to the National Advocate newspaper:

“Sir, In answer to numerous questions relative to the removal of the bones of the greatest man of the age, in which he lived, who lay in a state of degradation, and whom, as an Englishman, I claim as my countryman, I have to say we mean to raise a colossal statue in his memory, which will prove to you, in the first place, the value we as Englishmen set upon the merits of Mr. Paine; and on the other hand, will prove to you, as Americans, your ingratitude, neglecting, as you have done, the man, who had done more, ten times told, than any other person, towards emancipating America from British slavery. However, Mr. Paine’s remains are gone to the land where they will be honored; and, being instrumental in the removal, forms one of the happiest periods of my life.”

(Benbow appears to have had a very mean life indeed if he counts thieving a corpse from a grave at night like the resurrectionists of the period as the happiest time he had experienced.)

The editor of the City of Washington Gazette in November, 1819, wrote that “It must be admitted that Mr. Paine, with a few honorable exceptions, has been treated very scurvily in the United States…..Mr. Paine believed in a future state…in his treatise on dreams & c. (he) expressly states that he expected to exist hereafter. In truth, he was of too philosophical a turn of mind, and had too logical an intellect, to believe anything else. His infidelity extended no farther than to an unbelief in the Divinity of the Christian system. “

The editor of the City of Washington Gazette in November, 1819, wrote that “It must be admitted that Mr. Paine, with a few honorable exceptions, has been treated very scurvily in the United States…..Mr. Paine believed in a future state…in his treatise on dreams & c. (he) expressly states that he expected to exist hereafter. In truth, he was of too philosophical a turn of mind, and had too logical an intellect, to believe anything else. His infidelity extended no farther than to an unbelief in the Divinity of the Christian system. “

Paine had thought he would be buried in the Quaker church cemetery near his New Rochelle farm, but upon his death in 1809, that congregation refused him from being interred in their consecrated ground due to his unconventional religious beliefs, or lack thereof.

The public was so enthralled by the story of Tom Paine’s travels after death, one unknown author even wrote a witty and dark poem about it, which appeared in the New York Daily Advertiser. Some sample verses include what happened once Cobbett arrived in England with his moldy cargo:

“He grasps the atheist’s skull and cries—

Here are the bones of mighty Paine,

Bro’t in this box across the main—

His dreary grave I search’d and found,

And dug these reliques from the ground—

A spot neglected, wrapp’d in gloom,

A dismal, cheerless, hopeless tomb,

With briars and nettles overspread,

And covered with the hemlock’s shade.”

One wonders what Edgar Allan Poe would have done with this sort of inspiration: perhaps Paine would have quoth “Nevermore!”

Back to Cobbett & co., when he arrived at Liverpool, his luggage was taken from the vessel to the custom house to undergo the usual inspection. When the last trunk was opened, Cobbett observed to the surrounding spectators, who had assembled in great numbers “here are the bones of the late Thos. Paine!” This declaration exacted a sudden and visible sensation, and the crowd pressed forward to see the contents of the package. Cobbett remarked that “great indeed must that man have been, whose very bones attracted such attention.”

The customs officer took out a coffin plate, inscribed “Thomas Paine, aged 74, died 8th June, 1809,” and having lifted up several of the bones, replaced the whole and passed them. The captain of the Hercules did not know the trunk had human remains in it until he arrived in Liverpool.

To welcome the corpse thief Cobbett back home, some of his political friends in Liverpool decided to have a public meeting with a special dinner in his honor (it is not known if Paine was invited also), but the weather turned out to be treacherous with snow and ice, and not many turned out. Cobbett gave a lengthy justification for unearthing and importing Paine, particularly in having once abused the very man whose bones he now intended to honor. This he did by citing he had had immaturity of judgment and want of experience at the time he had attacked Paine in print in Philadelphia years earlier, and because Paine was then supporting the enemies of his country.

In a life he wrote about Paine in the early 1800s, Cobbett ripped him with the following poisonous pen:

“How Tom gets a living now, or what brothel he inhabits, I know not, nor does it much signify. He has done all the mischief he can in the world; and whether his carcass is at last to be suffered to rot on the earth, or to be dried in the air, is of very little consequence. Whenever or wherever he breathes his last, he will excite neither sorrow nor compassion; no friendly hand will close his eyes, not a groan will be uttered, not a tear will be shed. Like Judas, he will be remembered by posterity; men will learn to express all that is base, malignant, treacherous, unnatural, and blasphemous, by the single monosyllable__Paine!”

At the Liverpool dinner, Cobbett said his conscience hurt him about this earlier nastiness, and when he learned how Paine’s bones had been dishonored in America, though he was the founder of her independence, he determined to give his former enemy a more respectful and suitable burial. With respect to his object in bringing the bones to England, Cobbett declared it was to have them exhibited in London to as many people as might choose to see them, thus raising a sufficient sum to create a colossal statue to Paine’s memory.

Later, Cobbett tried to proceed with the plan further by going so far as to try to hawk rings made of locks of hair carefully clipped from Paine’s skull. This last venture appears not to have found many takers.

Within a year of the exhumation, Cobbett had gone bankrupt and had a stay in Newgate Prison, while Paine was exhibited by Benbow. Then the skeleton was stored away in a cellar at Cobbett’s home to enjoy some “quiet time” until Cobbett himself died.

In February 1836, the effects of the late William Cobbett Esq were put up at auction at his farm in the parish of Ash, near Farnham. Towards the end of the sale, a curious large box was brought forward. Auctioneer Piggott opened it, and stepped back quickly, aghast. It was Thomas Paine’s remains, wrapped in several papers. Piggott flatly refused to sell the contents, saying as he had never been a dealer in human flesh, he certainly wasn’t going to now sell human bones. The coffin plate of Thomas Paine was exhibited but went unsold, too.

Thomas Paine’s travels were just beginning, but the mystery of everything that happened to the remains, including his current status, remains a bone to gnaw on for historians.

In the 1870s, the trail of the remains focused mostly on Paine’s skull and right hand, which had stayed in the London area after Cobbett’s death. The second host of the bones was Lord King, a religious and political radical; then they went to a friend of Cobbett’s named Tillett, and disappeared for some years. The next appearance was in the study of the Rev. Mr. Ainslie of Brighton, a conservative Unitarian preacher, who claimed he had the skull.

“As that skull would be invaluable to the admirers of Paine, most of whom are believers in craniology or some kind of cerebral philosophy, Mr. Ainslie has been approached in various ways, but has thus far steadily avoided conversing on the subject. As the Rev. Mr. Ainslie has a good deal of fighting to do with the orthodox of Brighton, there is some ground for a suspicion that he does not wish it to come out that he keeps for secret homage the sacred ashes of St. Tom,” wrote a writer with tongue planted firmly in cheek for the San Francisco Bulletin in 1872.

So where are Thomas Paine’s remains now? Were they sold to a rag and bone recycler in England, as one tale says? Were they made into buttons? Were they dumped in the Thames? Were they kindly reburied? Or does the skull at least still stare out with sightless eyes through a cabinet of curiosities in some macabre collector’s study, the skull that held the mind which one day long ago opined, “These are the times that try men’s souls.”

Recent Comments