Yellow Fever: Napoleon’s Most Formidable Opponent

July 8, 2014 in American History, Caribbean History, general history, Louisiana History, Nautical History

By Pam Keyes

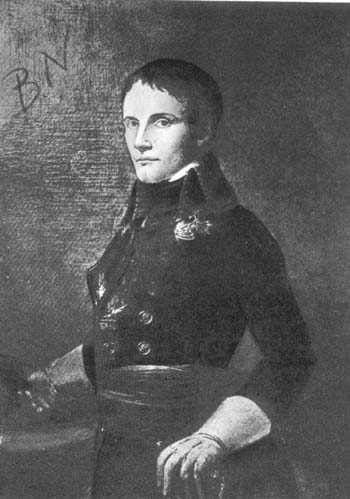

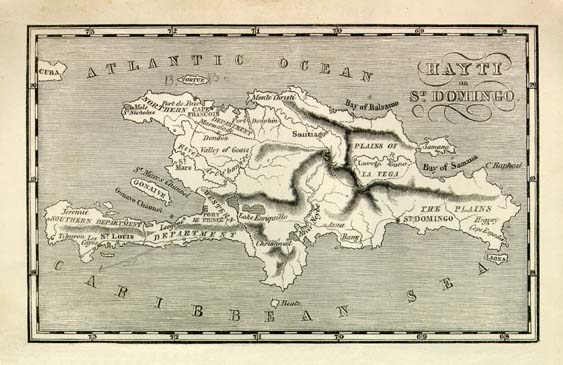

In mid-1802, French general Victor-Emmanuel LeClerc took up his pen to write back to his superior and sighed in the dripping, humid heat of Port-au-Prince. His brother-in-law, Napoleon, thought it would be an easy mission to quash the latest slave uprising on the island of Haiti and French-controlled colony St. Domingue. After all, he had sent 20,000 seasoned French troops to supplement the St. Domingue garrison and assist LeClerc in ending the terror on French planters and colonists caused by marauding black slaves and maroons hiding in the mountains around Port-au-Prince and elsewhere in the country. LeClerc himself had believed they would have the rebellion ended in a few months, but there was one factor they had failed to take into account, an infinitesimally small enemy that would kill more Frenchmen than all of the black rebels could ever have slain: the dreaded virus of yellow fever.

From 1802-1803, yellow fever at St. Domingue ravaged almost 50,000 French soldiers due to their lack of immunity to the disease, plus the medical ignorance of their doctors in ways to successfully treat a fever. The ports of St. Domingue, particularly the main one at Port-au-Prince, were surrounded by quagmires and swamps, prime breeding grounds for mosquitoes during hot and humid times of spring and summer. After being bitten by an Aedes aegypti mosquito carrying yellow fever, the victim would get either a mild or a severe form of the disease a week later. Symptoms included headaches, fever, muscle cramps, nausea, a black vomit, and in the worst cases, delirium, coma and death. At one point in early summer 1802, the men were dying at the rate of as many as 50 a day. LeClerc himself fell victim to the disease late in 1802. Children under 18 usually got the mild disease, and once they had had it, were immune for life, so the French planters’ children on the island were mostly safe, as were the natives of the island, and most of the slaves, who had acquired immunity in Africa. Safe also were older residents of the island who had had the mild form in their youths.

Some 20,000 additional French reinforcements were sent to supplement the surviving troops in late 1802, and LeClerc was replaced by General Rochambeau. By November, 1803, Rochambeau retreated to France with only 3,000 survivors. Almost twice as many French troops were felled by yellow fever on the island of Haiti than were slain in the Battle of Waterloo years later.

Napoleon reacted decisively to the slave insurrection victory due to the epidemic sickness of the French troops. He had met his match in a disease he couldn’t conquer, so he abandoned all ideas about expanding the empire into the Louisiana Territory of the US, and offered it for sale to the Americans for $15 million. The purchase agreement was signed in late 1803, doubling the US in size with a penstroke. Haiti declared its independence in 1804, becoming the first independent nation in Latin America.

In the end, the US benefitted greatly from the land, port of New Orleans and Mississippi River waterways additions; the French lost a major sugar-producing colony plus the chance for expansionism; and the slaves of St. Domingue (with the leadership of Toussaint L’Ouverture and Dessalines) accomplished the only successful slave revolt, all due to a microscopic virus that physicians could not properly treat nor understand at that point in history.

Recent Comments