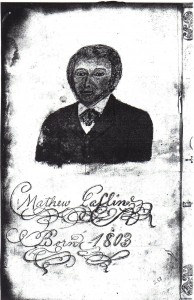

“The Journal of Jean Laffite” is a historical manuscript that surfaced in 1948 when John Andrechyne Laflin presented it to the Missouri Historical Society. He claimed that it was a journal kept by Jean Laffite from 1845 to 1850. The authenticity of “the Journal” has been questioned by many, and while not everyone believes it was written by Jean Laffite, it is an artifact from the latter half of the nineteenth century, is written in a hand that looks like the signature of Jean Laffite on his ship’s manifest, and does tell things from the point of view of Jean Laffite and in his voice, to the extent that we know his point of view and voice from other documents. Some believe that the Journal was not written by Jean Laffite himself, but rather by a close associate, one of his sons or by his second wife. Most, however, cast doubt on John Anderchyne’s role in bringing the “The Journal” to light, and many doubt his claims to be related to Jean Laffite.

“The Journal” is written in French and currently resides at the Sam Houston Regional Library and Research Center in Texas. It is not really a journal. It is much more like a memoir written toward the end of his life by an old man about events that happened much earlier. Not only that, but the journal is also a scrapbook.

Jean Laffite discusses martial law in New Orleans under General Andrew Jackson

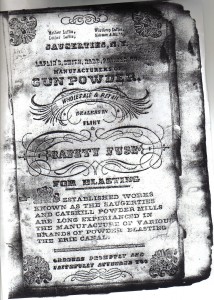

Kept in a memorandum notebook, the hand-scrawled memoirs are also decorated with scraps of newspaper clippings from a number of different years.

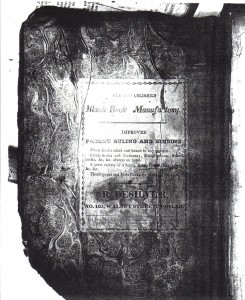

The inside cover of the scrapbook.

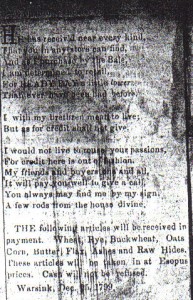

We can learn much about a man from the sorts of things he chooses to record and the types of events he never mentions. But equally revealing is the sort of material he chooses to clip from the newspaper and keep as a memento. Take, for instance, the clipping posted below. Written in rhyme, it tells the terms and conditions under which someone was willing to do business: trade or cash, but no credit.

A poem published in the paper by a merchant who was willing to trade or take cash, but would grant no credit.

In verse, the advertisement runs as follows:

He has received of any kind,

That you in any store can find.

And as I purchase by the Bale,

I am determined to retail

For READY PAY a little lower

Than ever have been had before.

I with my brethren mean to live

But as for credit shall not give.

I would not live to rouse your passions

For credit here is out of fashion.

My friends and buyers one and all

It will pay you well to give a call.

You always may find me by my sign

A few rods from the house divine.

The following articles will be received in payment: Wheat, Rye, Buckwheat, Oats, Corn, Butter, Flax, Ashes and Raw Hides. These articles will be taken in at Esopus prices. Cash will not be refused.

Warsink. December 25, 1799.

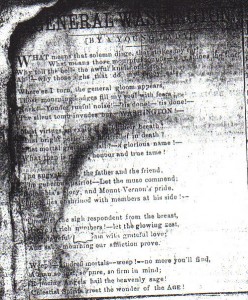

While arguably the reason Laffite kept that ad was not because of the verse, but because of the business arrangement that it describes, another clipping is a poem written by a young lady about the death of George Washington.

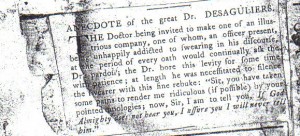

The poem, while not necessarily high art, does have a very solemn patriotic tone. But the journal is not always solemn, and the clippings are sometimes humorous. Here is an anecdote about swearing that was clipped into the scrapbook of Jean Laffite.

The above clipping tells an anecdote about a Dr. Desaguliers. The Doctor was invited to a party with “illustrious” company, one of whom, an officer, kept swearing and then apologizing for having sworn. This went on for some time, until, tired of this, the Doctor said: “If God Almighty does not hear you, I assure you I will never tell him.”

What can we learn from “The Journal of Jean Laffite”? Most of the facts it relates about his life are already well known. Those facts that are under dispute, will probably remain under dispute. But the scrapbook of Jean Laffite is another matter entirely. From it we can learn about the character of the man who kept it, what he found amusing, poignant, funny or worthy of note.

Sometimes it is not what we say about ourselves that matters the most. It’s how we see others and which of their writings we value that reveals our own true character.

Copyright 2013 Aya Katz

Although the “Journal of Jean Laffite” was introduced to the public by John Andrechyne Laflin, a person with a shady past and a reputation as a forger, we cannot entirely discount his claim that there was some connection between the well-established Laflin family and Jean Laffite.

Although the “Journal of Jean Laffite” was introduced to the public by John Andrechyne Laflin, a person with a shady past and a reputation as a forger, we cannot entirely discount his claim that there was some connection between the well-established Laflin family and Jean Laffite.

Recent Comments