Eyewitness Pension Record Testimonies Place Jean Laffite at Battle of New Orleans

February 21, 2018 in American History, general history, History, Legal History, Louisiana History, Nautical History

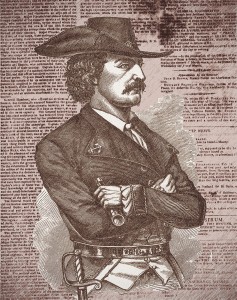

Privateer-smuggler Jean Laffite’s active service at the Battle of New Orleans on Gen. Andrew Jackson’s line is firmly verified by eyewitness testimonies found in newly digitized pension records of the National Archives at Washington, D.C. The documentation is part of the lengthy official correspondence widows of Baratarian veterans of the battle had with authorities of the Pension Office trying to obtain bounty land and monthly pensions in the mid to late 1800s.

The service verification is highly significant as it is the only documentation in the official records that attests to both Pierre and Jean Laffites’ actions at the Battle of New Orleans (BONO), in command of two small companies of their men. Historians had been unable to locate these testaments as the handwritten documents were hidden in pension records, not indexed by content, and oddly the facts of the matter never were a part of the official militia rolls. Thus many have said Jean Laffite in particular wasn’t present at the Battle of New Orleans, as depicted in the two “Buccaneer” movies…..but he was, according to the testimony obtained from five veterans. They testified to help two widows whose husbands both were part of the cannon crews around Battery No. 3 and 4 with Dominique You, Beluche, and fellow Baratarians who had been with Jean Laffite previously at the privateer/smuggling base of Grande Terre.

The women, Adeline Godin Maire and Catherine Looski Joly, were seeking government old age benefits available to veterans of the War of 1812 or their widows, approved by Congress in 1878, and earlier in the 1850s, bounty land grants approved for veterans. Both of their husbands, Lorenzo (Laurent) Maire (aka Meii) and Victor Stanislas Louis Joly, respectively, served as cannoneers, crewing the 24-pounder cannons placed there on the embankment behind the Rodriguez Canal at Chalmette plantation. Those two cannons were the deadliest to the British, and most accurate, according to one British soldier’s later account.

Particularly important to Laffite’s role is the detailed testimony under oath given by BONO veteran Jacques Meffre Rouzan for the case of Mrs. Joly in court at New Orleans on Feb. 16, 1881. According to the justice of the peace account of the testimony, Rouzan said “he remembers Louis Joly as having served in one of the artillery squads under Captain Lafitte, the pirate, at the time of the invasion by the British in 1814-15 and at the battle of New Orleans, Jan. 8, 1815. That there were two of the Lafittes, brothers, Pierre and Jean, and each had charge of a squad of ten or fifteen cannoneers that they commanded ‘at the lines,’ that is at camp Chalmette, and in the battles that were fought there on the 23 of December and 8th of January. That he distinctly remembers Louis Joly, a white man and a Frenchman, as being a member of one of those squads, and as having been on duty therein ‘at the lines.’….that he also remembers one Dominique Yeux who was one of Lafitte’s cannoneers.”

Earlier testimony for a bounty land grant for Mrs. Joly by BONO eyewitness veterans Barthelemy Populas and Jacque David St. Herman strengthens support for evidence of the Laffite Company. On August 13, 1857, they stated under oath that they saw Louis Joly “in active service of the US in the two battles of New Orleans during the British invasion in the company of artillery commanded by Capt. Lafitte…generally known and called by the natives ‘Lafitte le Pirate’ of whom so much has been said in connection to his brave conduct in the defense of New Orleans.” They added that Joly served about 14 days in the battles and was discharged together with Jean Baptiste Latour and Vincent Gambie of the same company in New Orleans on or about the month of March 1815.

The BONO witnesses’ testimonies are crucial confirmation Laffite was actively in place on Jackson’s line at the Battle of New Orleans, documentation of which is not to be found anywhere else in military records, despite research by numerous historians over the years to find such proof. The only documented record of the Laffite brothers’ service of any note came from a couple of Jackson’s military orders and a brief acknowledgement by Jackson of their “courage and fidelity” in a published statement after the victory against the invading British. In 1827 in a letter to a friend, Jackson also said the sole source of the flints for the American side came from the Baratarians, meaning the Laffites. He never specified exactly how the Laffites served. However, the story the two pension applications tells points out that the truth of the Laffite brothers’ service was for some reason absent in the official military records of the volunteer militias that were fighting on Jan. 8, 1815. This is decidedly strange considering the pardon President James Madison offered to any Baratarian who served in the American side of the battles and could provide proof of service from Gov. Claiborne. The pardon named no individuals, but clearly Washington authorities were informed of the Baratarians’ service. Neither the Laffites nor most of the Baratarians ever applied for their pardons.

The book most historians regard as an exhaustive history of the Battle of New Orleans in particular, “A Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana, written by Jackson’s chief engineer Arsene Lacarriere Latour and published in 1816, does not mention this Laffite company as such, which is curious considering Latour was a best friend of Jean Laffite. However, other particulars regarding Jackson’s forces are not to be found in the book, either, some of which were to have been included in a second edition which was never made. Latour did tell Spanish authorities at Cuba in 1817 that his friend, Jean Laffite, had conducted himself with courage at the Battle of New Orleans.

The Laffite participation on the American side of the war against invading British forces was ignored officially. Indeed, as Commissioner of Pensions Wiilliam W. Dudley wrote in Dec. 22, 1882 to Mrs. Maire in response to her pension applications, “There is nothing in history known to this office or in the archives of government which credits Captain Lafitte (sic) with having been in the United States service during the War of 1812.”

In endeavoring to obtain their pensions, the two elderly ladies needed to amass a wide array of proofs, which included locating their husbands’ names on the official military rolls of the various companies. They were stymied in this, as like the Laffites, neither Lorenzo Maire nor Louis Joly was found on any roll, and according to an official letter from the auditor’s office dated Dec. 30, 1856 to Mrs. Joly, “Service is alleged to have been rendered in Capt. Dominique’s Co. La Mil in the War of 1812, but there is no evidence of that command (Dominique’s)” [!] Yes, even though Dominique You was widely revered in New Orleans and received a funeral with honors when he died in 1830, the official roll of his service was NOT in its right place in the military records at Washington….until Mrs. Joly and Mrs. Maire persistently asked someone to look for them, Mrs. Joly, a semi-literate, through her lawyer, and Mrs. Maire, through both a lawyer and her own letters to the Pension Office.

In May 1858, Mrs. Joly received a letter from George Eustis of the Pension office which stated “I have the honor to inform you that the bounty land claim of Mrs. Joly, widow of Victor S. Louis Joly dec’d referred to…has been suspended under repeated reports of the Auditor that there was no evidence of Capt. Dominique’s Command La Mi; War of 1812. But it appeared that rolls have been found within the last month, and the claim is now again referred to that officer for further examination, the result of which will be communicated to you…”

(Mrs. Joly was approved in the 1850s for a bounty land grant which apparently got overtaken in the mails, as she never received it, and had to post an ad in the Picayune newspaper of New Orleans alerting the public not to purchase the land from the holder of her grant. Several documents in the pension files show she also tried to obtain a replacement grant, which did not meet with success.)

To get a snapshot of the two Baratarians involved in these cases, they were described thusly by their respective wives: Maire (also known by the surname Meii) was a native of Italy, 5’7” tall, with dark complexion, black hair and black eyes, about 24 years old at the time of the Battle of New Orleans: Joly was a native of France, about 20 years old at the time of enlistment, 5’6” tall, with fair complexion, gray eyes and dark brown hair. Maire died in 1827; Joly, in 1856.

Adeline Maire’s case for Lorenzo’s pension is particularly significant in relation to both Jean and Pierre Laffite as Lorenzo Maire was known as their brother-in-law although Adeline Godin Maire was not their sister; apparently, Lorenzo had been married earlier to a Laffite sister who had died. Lorenzo was with the Laffites at New Orleans as early as 1812, and had been a privateer captain for them during the time they were at Galveston in 1817-1820. New Orleans Diocese records show that Adeline Godin and Maire were married by Father de Sedella at New Orleans on Dec. 16, 1817, when she was 17 and Lorenzo was 27.

Adeline pursued her widow’s pension intently, concentrating on the fact that Lorenzo had served in the “Lafitte Company.” Her attorney George W. Dearing did his best, writing to Dudley on August 16, 1881, enclosing two affidavits from eyewitness veterans of the Battle of New Orleans in support of her pension case under the Congressional Act of 1878.

Dearing added “I think it strange that there is no record of the men who served under the compact between General Jackson and Capt. Lafitte, for it is a historical fact that all of Lafitte’s men did serve, and did good duty during the siege of the British at New Orleans in 1814 and 1815 during Dec. and Jan. and the efficient and signal service rendered by Dominique You (one of the vessel captains under Lafitte) is well known, every survivor knows that Dominique You’s crew was assigned to a cannon on the US breastwork and that they did yeoman service, and we have heretofore shown by two credible veterans that they saw Maire or Meii under Dominique You doing duty, now Mr. Varion swears to service but only remembers him as one of those who belonged to Lafitte’s crews.”

Dearing’s letters did not elicit a favorable response, so the frustrated Mrs. Maire began deluging Dudley with her own letters.

“The chiefs in Command was (sic) Jean Laffitte and Pierre Laffitte and were pardoned by Gen. Jackson on condition that they would join the American forces_and was (sic) enrolled by Gen, Jackson’s orders in the Louisiana Militia. The officers in chief were Jean Laffitte, Pierre Laffitte, Gambi, Dominique Youx,’ wrote Mrs. Maire in response to a request for officers of her husband’s company.

On May 24, 1882, she wrote the following from New Orleans to Dudley at Washington, D.C.:

“…I will simply state that my husband Lorenzo Maire did serve as one of the Company commanded by Pierre Laffitte and Jean Laffitte as has been stated and sworn to by Francois Varion and Mr. Eugene Ducas whom has served (sic) and are drawing their pensions from this office and who has been well acquainted with my husband before during and after the Battle of New Orleans in 1814 and 1815. Mr. J. M. Lipace also has served in said battle and was also perfectly acquainted with my husband and he is also positive and certain that my husband did serve by referring those gentlemen which are still living and receiving their pensions through this office will I suppose be a sufficient proof of my assertion.”

She added that she had been receiving a Louisiana state veterans’ widows’ pension for a few months but in 1876 that pension was stopped.

On the back of her letter, some official with the Pension Office nastily scribbled: “The Pirate Lafitte does not appear to have been recognized by the US government,” adding that Maire’s witnesses were not considered satisfactory to determining eligibility in the case, but that note remained in the Pension Office files.

When Mrs. Maire did not receive a positive reply from Dudley, she wrote back on Dec. 2, 1882, repeating her claim that Lorenzo did serve in the Company of Artillery commanded by Capt Laffitte, General J.B. Plauche’s Division Louisiana Militia during the War of 1812, Battle of New Orleans in 1814-1815. Frustrated by the bureaucratic stone wall, Adeline wrote “The existence of Capt. Youx Company and the services rendered by said company during the Battle of New Orleans War of 1812 has been clearly furnished and in this company my husband Laurent Maire did serve Furthermore, Capt. Youx died in New Orleans and was buried in the St. Louis Cemetery by charity.”

Mrs. Maire’s case dragged on, unsuccessfully, through 1883, and you can feel her frustration with the Pension Office in her letter of April 25, 1883 to Dudley, who was insistently requesting fellow officer’s testimony from the Laffite Company to verify her claim, even though 68 years had passed since the time of the battle.

“The officers and privates of Capt. Lafitte’s Company of artillery Louisiana Militia Gen. J.B. Plauche’s Division are all dead and buried and therefore it is impossible for me to raise their dead bodies in order to comply with the proofs required by the United States government or the Pension officers. This power is only Given to God the Creator of the United States government and its officers which no one can deny,” wrote Adeline.

Dudley ended the communication in October 1883 with a partial form letter filled in by himself, repeating the there was no evidence of service, so the claim must remain rejected, inasmuch as nothing within the power of his office to complete this case had been left undone, further correspondence would therefore be unheeded.

Neither widow ever received their US pensions. Mrs. Maire died in 1891, and Mrs. Joly, in 1878. Oddly, the Pension Office did reimburse Mrs. Joly’s two daughters for part of her funeral expenses.

The elderly eyewitness veterans of the Battle of New Orleans, Francois Varion, Eugene Ducas, Jacques Meffre Rouzan, Barthelemy Populas and J.D. St. Herman, all had received their pensions at the time of their testimony for the two women. In an intriguing twist to the cases, those eyewitnesses all apparently were members of the “Association of Colored Veterans of 1814 and 1815” at New Orleans, a group chartered in 1853 by free men of color who were Battle of New Orleans veterans. Their goal was to help fellow claimants and survivors qualify for benefits at the state and federal levels, and they assisted black and white families alike. Most of the men had been part of the Lacoste and Daquin battalions who could testify for the Laffite units easily since they were quite close by on Jackson’s line on Jan. 8, 1815, as shown on Latour’s map. The survivors who testified in the 1880s had been young men at the time, and the battle had been indelibly etched in their memories.

It is a mystery why the Pension Office refused to accept the eyewitness testimony from Jackson’s line. Perhaps it may have had something to do with Dudley, who was appointed Commissioner of Pensions in 1881. He was a Union veteran of the Civil War, and no doubt had little sympathy for anyone in the South, considering he had lost part of his right leg and most of the men in his unit at Gettysburg.

Today, the Chalmette battlefield is known as part of the Jean Lafitte National Historical Park, but that name was given to it in the 1980s for regional reasons, not to honor Laffite for the Battle of New Orleans itself. The newly discovered eyewitness testimony proves the name of the park is merited by honorable service long denied.

Related

Commemoration of a Hero: Jean Laffite and the Battle of New Orleans

Recent Comments