The Letter That Tried to Scuttle the Baratarians’ Pardon

October 10, 2015 in American History, general history, History, Louisiana History

If George Poindexter had been Sec. of War or President during the end of the War of 1812, the Laffites and Baratarians would never have been pardoned for their past smuggling offenses even though they had given service and assistance to General Andrew Jackson at New Orleans.

Poindexter, who served as a volunteer aide de camp with Major General Carroll at Chalmette, took time away from his role as a judge at Natchez, Miss., to assist Jackson in defending New Orleans from invading British forces.

As soon as he returned home to Natchez, he wasted no time in firing off a confidential letter about his New Orleans experiences to his friend, Sec. of War James Monroe. The content about the pardon process is interesting as it contains some new information:

“Even a band of pirates was drawn into our ranks who were under prosecution of their crimes, and who had been invited to join the British while they occupied the Island near Lake Barataria. You will I hope sir, pardon me for stating to you, the manner, the circumstances of their transition from piracy to Patriotism, in the notorious Lafitte and his banditti. Edward Livingston, whose character is better known to you than myself, had contrived to attach himself and one or two of his adherents to the staff of Genl Jackson, as Volunteer Aids DeCamp (sic). The pirates had previously engaged him as their counsel to defend them in the District Court of the United States at New Orleans, and were by stipulation to give him the sum of twenty thousand dollars in case he succeeded in acquitting them. Knowing as he did that the evidence against them was conclusive, and that an impartial jury necessarily convict them, he advised the leaders of them to make a tender of their services to Genl Jackson in case he would come under a pledge to recommend them to the clemency of the Executive of the United States. Their services were accepted, and the condition acceeded to. How far the country is indebted to them for its safety it does not become me even to suggest an opinion. It is, however, a fact perfectly well known that their energy has been drawn by Mr. Livingston, their counsel; and there can be but little doubt that everything of an official stamp which is presented by the government respecting them, will emanate from the same source. If they are redeemed from Judicial investigation of their crimes with which they stand charged, his reward will be twenty thousand dollars of their piratical plunderings.

What the practice of Civilized Governments has been on similar occasions I am not fully prepared to say, nor do I remember an instance where pirates falling into the Country and under the power of one belligerent, have been offered protection and pardon of their offences, in case they would take up arms against the other belligerent. They are considered as enemies alike to both belligerents but I have thought it a duty incumbent on me as a good citizen to state the facts which came within my knowledge, as to the motives which led to the employment of these men, without intending them to have any other, than the weight which is your Judgment they merit.

It would seem to be an obvious inference from the past conduct of this band of robbers that if Louisiana should be again invaded, and they are enlarged, they would be restrained by no moral obligation from affording facilities to the Enemy.

I indulge the hope that you will pardon the freedom with which I address you on the present occasion, from a recollection, that when I last had the honor of an interview with you in Washington, you were so good as to allow me the liberty of writing to you confidentially. In that light, I wish you will view this communication, in so far as it may conflict with the wishes and opinions of General Jackson, relative to the grant of a pardon to the pirates, whom he has thought fit to employ in our service.”

Signed, George Poindexter

Poindexter’s rather snippy revelation about Livingston’s fee for representing the Baratarians may or may not have been true. It could have just been battlefield hearsay. If the fee was really $20,000 in 1814 dollars, it would be the close equivalent to $200,000 today.

The letter implies but does not say that Livingston influenced Jackson to accept the Baratarians’ service as a way to ensure he would get his enormous fee. Poindexter hatefully says “it does not become me even to suggest an opinion” relative to the Baratarians’ contribution to the safety of the country. He conveniently forgets the vital contribution of the Laffite flints and powder to Jackson, plus the Baratarian cannoneers’ service. Without them, Poindexter likely would have found himself cooling his heels in a British prison ship on Feb. 5, 1815, instead of comfortably at home in his Natchez mansion.

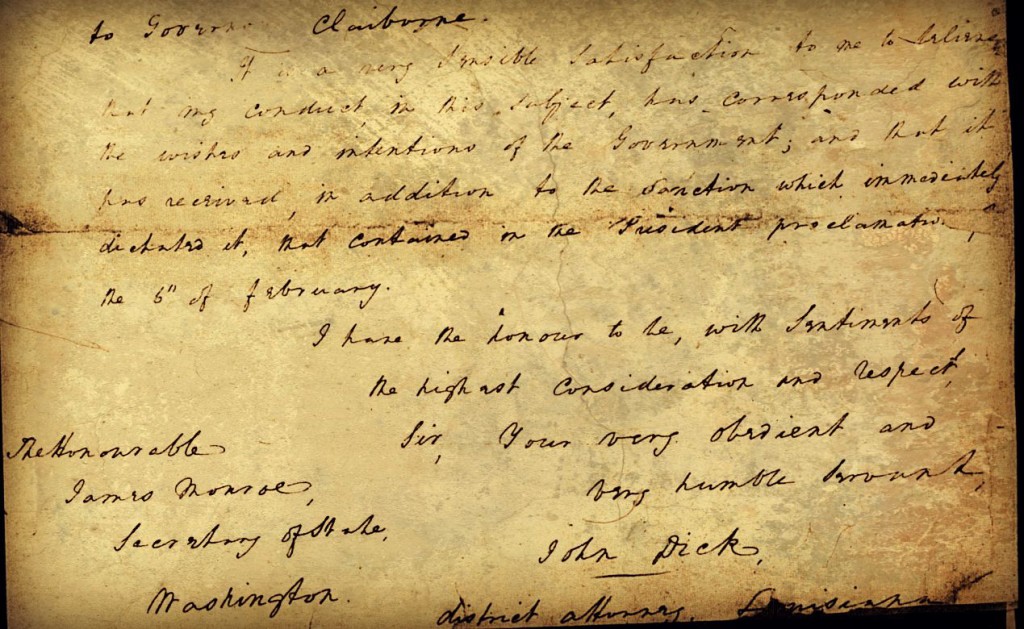

Thankfully, however, Poindexter’s letter was much too late to even have a chance to stop the presidential pardons for the Baratarians. The same day Poindexter wrote his letter, Monroe sent a letter to Gov. Claiborne enclosing the signed pardons. They had been rushed through the pardon process at record speed, especially considering President James Madison and his cabinet were basically dislocated in Washington at the time and conducting business somewhat haphazardly from various houses. By the time Poindexter’s letter was in Washington, the pardons were in Gov. Claiborne’s hands.

There also happened to be another reason the pardons were accelerated: Monroe was secretly something of an ally to the Laffites and their men, through their mutual friend, Fulwar Skipwith, president of the Louisiana State Senate in 1814, and former President of the short-lived Republic of West Florida in 1810.

Along with Magloire Guichard, Speaker of the House of Representatives in the Louisiana state legislature, Skipwith had sponsored a resolution to grant amnesty to “the privateers lately resorting to Barataria, who might be deterred from offering their services for fear of persecution.” This was done around mid December 1814, not long before General Jackson shut the legislature down due to civil unrest within it. Skipwith must have informed Monroe about this very soon after it happened, with Jackson accepting the services of the Baratarians who were freed from prison, plus others who had not been caught in the September 1814 raid on Barataria, like the Laffite brothers. Due to wartime blockades of sea traffic by the British, letters had to be sent by post rider back east, with the time to delivery often being as much as a month or more. The request for presidential pardons from James Madison must have been made before the Battle of New Orleans, given that Monroe enclosed the pardons in his letter to Claiborne on Feb. 5, 1814.

The real reason the presidential pardons were fast-tracked lies in an understanding of the web of influence and political power between the Laffites, Skipwith, and Monroe. Even if Poindexter’s letter trying to defuse any possibility of pardons for the Baratarians had been received in time for consideration, in all probability it would never have been read by President Madison.

Monroe and Skipwith were old friends, from at least their days together in France, where Monroe was ambassador in 1795 when he named Skipwith to be the US Consul-General to France. Both men worked in the Napoleonic court together, fine tuning the Louisiana Purchase. Both men were Masonic brothers. Also, both men shared strong ties to Thomas Jefferson, Skipwith by relation as a distant cousin, and Monroe as a neighbor and very close friend.

There is a question of how Skipwith became associated with the Laffites. The most likely manner occurred not long after the Virginian moved to a plantation in Spanish West Florida in 1809. He started running privateers, at about the same time the Laffites were setting up their own smuggling and privateering business. No paper proof has been found linking them, but the actions of Skipwith in 1814 favorable to the Laffites would seem to indicate that they were, indeed, associates of some kind. Thus the Laffites had friends in some very high places.

Only a handful of Baratarians ever retrieved their pardons. The Laffites never applied or received any. Nor did Dominique Youx, the main gunner at Battery No. 3, or Renato Beluche, also a gunner at Battery No. 3.

As for what happened to George Poindexter, the man who wanted to deny pardons to the Baratarians despite their service to Jackson, he became the second governor of Mississippi and had a moderately successful political career.

Skipwith and Monroe kept up their correspondence for several years and apparently were lifelong friends.

For further reading about the hidden gems of early American history, I heartily recommend perusing Daniel Preston’s fine “A Comprehensive Catalogue of the Correspondence and Papers of James Monroe.” Thanks go to him for providing the Poindexter letter copy from the Monroe Papers. For more about Fulwar Skipwith, the man with the memorable name, and the Republic of West Florida, see William C. Davis’ “The Rogue Republic, How Would-Be Patriots Waged the Shortest Revolution in American History.”

Recent Comments