Pirates, Privateers and Ethics in the New Orleans Courtroom

November 18, 2017 in American History, general history, History, Legal History, Louisiana History, Nautical History

Ethics meant everything to attorney John Dick, an Irish emigrant to New Orleans. He felt compelled in May 1813 to ensure everyone else knew that, too, even if it meant possibly provoking a duel with his nemesis, District Attorney John Randolph Grymes, over a recently completed case involving a French pirate Grymes had represented in New Orleans District Court. So as soon as he was free of his sick bed, Dick proceeded to the offices of the leading newspaper in town, the Louisiana State Gazette, and gave the editor his lengthy exposition of just how badly he thought Grymes had neglected his official duty in order to profit from the purse of a pirate. The case involved the Spanish poleacre San Francisco de Paula versus the captain and crew of the armed French schooner Felix

The editor of the Louisiana State Gazette of May 29, 1813, prefaced Dick’s two page missive with the following:

“Publication of the following statement has been delayed by a variety of causes. At the period of its date, and for sometime afterward, the case to which the facts in the statement have reference, remained undecided. Consequently to have made the facts a subject of newspaper discussion would have been disrespectful and improper. This reason for delay was assigned by the writer through the public prints, early in the month of February (1813); and, at the same time, he pledged himself to a justification of his dispute with Mr. John R. Grymes, as soon as that justification could be made consistently with duty and decorum.

“When the case of the San Francisco de Paula was decided, an important change had taken place in the writer’s situation,_and his life, previously despaired of, was considered out of danger_then, he thought it better to delay his defense until freed from the trammels of a sick bed so he could give it his personal attention; but now, on due reflection, he presents it in its first form as written at the time of its date. This form is chosen by the writer in preference, as it displays his feelings and dispositions at that period, although he is aware of the imperfections necessarily included to so indigested a production….”

(Ed. note: the decision of the court was to restore the San Francisco de Paula and cargo to the libellants, so Dick won the case for his clients, but apparently the questionable ethics of his opponent still nettled him.)

Here, as follows, is most of Dick’s letter:

“New Orleans Jan. 27, 1813

TO THE PUBLIC

An urgent but disagreeable necessity forces me (John Dick), in defense of my own honor, to lay before the world the circumstances of a personal quarrel. Society is so regulated that in proportion as an individual becomes the object of suspicion or the theme of reproach, so if his utility impaired, his capacity to benefit the community or himself is enervated or destroyed. Impressed with this truth, and influenced by the intention of rescuing my character from the [taint] that justly attaches to him who falsely or unnecessarily assails the reputation of another, I have thought it proper thus to address the public.

The following statement …is a history of my own motive and conduct, written in order that, if living when this meets the public eye, I may be justified to the world, and may not lose that utility which the loss of the world’s good opinion would deprive me; or that if dead, my character may rest in peace_unsullied by the malevolence of those who bear me enmity, free from the censure of the ignorant or misinformed.

I have been charged by Mr. John R. Grymes with making a wanton, and unwarrantable attack on his character and reputation. This charge is eminently serious; it involved everything that is dearest to man; and in its consequences, may lead to a catastrophe much to be deprecated. To Mr. Grymes I have no feelings of personal hostility, but I have regard for justice and the truth…feelings that now urge me to repel with vigor an unjust accusation. If I am indeed capable of a wanton aspersion of character_if I am capable of willful injustice, of knowingly perverting what I understand, I no longer deserve to live in the society of those who deem a strict and inviolable adherence to truth, the groundwork of all that is virtuous and honorable among men__I proceed to a development of my alleged offense and to my justification.

It was in the District Court of the Louisiana District on the 19th of (January 1813), in the case of the Spanish poleacre the San Francisco de Paula, that I found it necessary in the course of the argument to advert to the system of piracy practiced in our seas__this system, which mocks all lives human and divine, which banishes all the charities of life and dissolves all the sympathies of nature, which, if countenanced, confounds all the distinctions of morals, and bursts the ties of society asunder by giving a license to power to prey upon weakness__this system, I say, I considered likely to be influenced by the decision in the pending case; on the one hand that it might tend to suppress the evil, or on the other, that it might give increased energy to its aggressions on the morals and happiness of society.

After endeavoring to impress the court with the importance of this subject, and after calling its attention to the alarming influence and progress of piracy and illegal adventures within its immediate jurisdiction I went on to express myself nearly as follows:

“What, indeed, it may be asked, is the condition of the community when he whose duty it is to guard the law from infraction and to enforce it, is found active in giving efficacy to the conduct of its violators? When the sentinel, not content with sleeping on his post, gives security to illicit operations by becoming its defender, we may well say that it is time for the citizen and the neutral to look elsewhere for an enforcer of the laws that afford them security and protection. And where can they look with so much security, with so much certainty of success, as to the enlightened tribunal which I have the honor to address?”

The person alluded to in these observations was Mr. Grymes, the district attorney; and I think the following narrative of facts will demonstrate not only their truth and justice, but their necessity to the subject under discussion.

The Spanish poleacre San Francisco de Paula, from Palmyra in the Island of Minorca bound for Havana, was captured off Matanzas on or about the 21st of last June by the armed schooner Felix, alleged to be a French privateer duly commissioned. The Felix brought her prize into the port of New Orleans, where the captain of the policer instituted a suit in the district court of the US for retribution of vessel and cargo alleging that the armed schooner Felix was not a privateer duly commissioned, that she was illegally fit out, and her force illegally augmented within the waters and jurisdiction of the United States.

I was one of the counsels for the captain of the poleacre libellant, Mr. Grymes, district attorney of the US in and for the Louisiana District, was one of the counsels for the captain and crew of the Felix, claimants.

In the progress of the cause it appeared in evidence that soon after the arrival of the San Francisco de Paula in the port of New Orleans, Captain Patterson of the navy, then commanding officer on this station in the absence of Commodore Shaw, applied to Mr. Grymes, as district attorney of the US, to institute a criminal prosecution against the said schooner stating that an examination of her papers, conducted with attentive scrutiny on his part, led him to consider the said schooner a Pirate. Upon this application, Mr. Grymes did not think proper to act; he saw no sufficient grounds for instituting a prosecution, and the Felix was permitted to go to sea without molestation.

It was further shown, by the testimony of one of the crew of the schooner Felix, that the said schooner had cleared out from Baltimore under the name of the Two Brothers; in ballast, and bound for Boston. That the witness shipped on board of her in the Chesapeake, at which time she was perfectly new, never having been to sea; that on getting to sea some arms and ammunition were produced, the name and character of the schooner were changed__she assuming the style and title of the French privateer Felix from Bayonne__that the Felix proceeded to Charleston, where she received an augmentation in her force of 22 men…These and other circumstances were related, all going to show distinctly and incontestably the character of the Felix, and affording full and satisfactory evidence that prosecution alone was wanting to condemnation of the vessel and punishment of the crew by the laws of the United States.

When the subject of this testimony was under discussion, Mr. Grymes, for the purpose of weakening its credibility and force, stated that it would have been sufficient to sustain a prosecution against the Felix, which would have been the most easy and ready means of obtaining restitution of the Spanish poleacre and cargo. In reply it was told to Mr. Grymes, that evidence struck different minds with different force that, as in the application made by Capt. Patterson, so in this case. He might have considered this evidence insufficient; that at the time of obtaining this testimony Mr. Grymes was counsel for the captain and crew of the Felix; that there was too much at stake (50-70,000 dollars) to risk its exhibition previous to trial for it was impossible to separate Mr. Grymes counsel for the claimants from Mr. Grymes attorney for the United States.

To show how entirely the conduct of the counsel for the claimants corresponded with these observations it is sufficient to state, that the testimony was disclosed to the acting collector of the customs while the Felix was yet in port__but in confidence, under an express injunction not to make it known to Mr. Grymes. Mr. Grymes was the only organ through which the collector could be expected to wage prosecution against the Felix; the conditions under which he obtained this information as a man of honor he could not violate; the district attorney was not consulted, the Felix rose at anchor in the Mississippi unmolested, and proceeded to sea without enquiry or interruption.

What evidence the counsel for the claimant had of the original outfit of the Felix I know not. From a circumstance, however, that occurred pending the case I have reason to believe it was full and conclusive. They were necessarily possessed of every means to obtain a correct knowledge of the facts in relation to the vessel. On our side, testimony was obtained with difficulty under every circumstance of disadvantage combating at every step the contrivances ingenuity had devised to smother enquiry. The result of the cause will show whether the efforts of the counsel were successful. The circumstance I have above alluded to, inducing a belief that Mr. Grymes, with others of counsel, was in full possession of the facts relating to the original outfit and subsequent augmentation of the force of the Felix, is the following. After three or four days had been taken up in examining testimony on the part of the libeling, and while no positive proof had yet been exhibited going to maintain the grounds of the libel, Mr. Grymes, the district attorney and of course for the claimants , in speaking of the case in the clerk’s office previous to the opening of the court, declared distinctly, unhesitantly and without reservation in my presence, and in that of several others, that he had no doubt the Felix was fitted out within the waters and jurisdiction of the United States but that we__the counsel for the libelists_could not prove it! __Here I pause. I rest my case.

I have endeavored to exhibit the truth and have neither time nor inclination to enter into reflections which in a thousand forms the subject presents. I have consulted only my own justifications, and I leave to the impartial and reflecting to say whether in the observations I uttered I was guilty of an unwarrantable attack on the feelings, character, or reputation of Mr. Grymes_No_Not one of all who are capable of comparing the relative situations of Mr. Grymes, counsel for the claimant, and Mr. Grimes, attorney for the US, but will say, that his part in the cause was incompatible with his official station, that it must necessarily conflict with the duties of that station.

I I do not pretend to say that it was the duty of Mr. Grymes to commence prosecution against the Felix upon the application made to him by Capt. Patterson. The evidence that appeared conclusive to Capt. Patterson might, in a legal point of view, have been insufficient. Of this, Mr. Grymes, from his official station and professional habits, was the better judge, and the presumption is, that in declining to prosecute the Felix. I do say the application ought to have awakened suspicion and enquiry on the part of Mr. Grymes, that ethically it ought to have forbidden his occupying the station of an advocate for this very vessel where the charges against her were piracy and infraction of the laws of the United States. Here it became the duty of Mr. Grymes, as counsel for the captain and crew of the Felix, to smother all evidence tending to conviction; and to seek an acquittal from charges, which as attorney for the US it was his duty to strengthen and sustain, by every means in his power. What opposites of reflections must this singular conflict of character naturally suggest to an unbiased mind! It presents a duplicity of situation which nothing can reconcile, which neither propriety nor delicacy can excuse…”

Signed John Dick

Not content to stop there, Dick continued to harp on how Grymes had unethically represented the presumed pirates, whom he should have prosecuted to perhaps end in their being hanged in New Orleans, since, as Dick stressed, “Piracy by the laws of the US is punishable with death.”

It is unknown exactly what response Grymes had to this lengthy public attack on his ethical character, but this was only the opening salvo to a long and sustained enmity between the two men which boiled over sometime in the fall of 1814 with a duel in which Grymes was shot in the calf and Dick got a serious wound to one thigh which left him with a limp for the remainder of his life.

Both Dick and Grymes were close in age, and young in 1813 when the Felix case came about, 25 and 27, respectively. Although Dick was a rising star at the time in the New Orleans community, he was not as popular as the gregarious high stakes gambler Grymes, who seems to have been the friend of everyone else in town except Dick. According to a description in a Louisiana State Bar Association report, “The manner of Grymes was singularly calm, and even in his speeches; betrayals of feeling were rare. His arguments were distinguished by a quiet, logical method of prosecution, and were always free of declaration. His voice was clear and musical, and under the most perfect control. Without appealing to prejudices or passion, he had yet a singular power over juries, rarely failing to gain a verdict.”

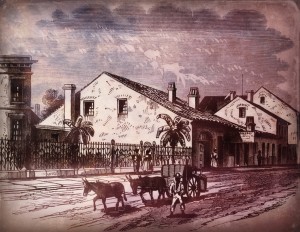

Grymes made something of a career after the Felix case of representing his friends, the privateer brothers Pierre and Jean Laffite, and their associates in court. He often battled legal cases against Dick in the small Spanish stucco style courthouse in the French Quarter. Some of these he won, some he lost. The most notorious Laffite case which Grymes lost was the Le Brave piracy case in 1819, which Dick, who had been District Attorney since February 1815 (assuming the role from Grymes), successfully prosecuted. The captain and men of the Le Brave were hanged, with the exception of two who received a presidential pardon.

For more about John Dick, and how once he himself had advocated for the Baratarian privateers, see my earlier Historia Obscura article “John Dick’s Letter to Monroe Honoring the Baratarians.”

John Dick was nothing if not a mercurial, impassioned individual.

Recent Comments