The True Tale of Mitchell, the Zombie Pirate

March 11, 2016 in American History, Caribbean History, general history, Louisiana History, Nautical History

When notorious Gulf Coast pirate William Mitchell came back from the dead in 1835, he looked like a zombie from Hell.

One-eyed, the man was covered with horrible scars, evidence of many deep and dangerous wounds he had suffered in his life. The worst of these the grey-haired 56-year-old bore in the front of his neck, where it appeared at some time a boarding pike or bayonet had been thrust completely through. According to the Philadelphia Herald of Oct.. 30, 1837, the pirate also “had a wound in the back of his neck, a musketball in his fore shoulder, had lost the calf of his leg from a splinter, and was otherwise marked upon his arms and legs.” Mitchell obviously had led a very hard “second life” after reportedly dying in 1821 on Great Corn Island off the Mosquito Coast in the Caribbean.

Several newspapers carried reports of his death in 1821. The Watchman of Montpelier, Vt. said in its August 7, 1821 edition that Capt. Mitchell had died on the first of May, and that he was “generally known by the term Pirate Mitchell as he has been several years privateering and pirating in the Gulf of Mexico, and on the coasts of South America. He was born at Bath, in England, and was several years an officer in the Spanish [Patriot] service.”

Much of the intervening time between 1821 and 1835 Mitchell had spent in various prisons, including at Norfolk, and the last two years at Philadelphia, where he was convicted on charges claimed by his wife of bigamy and assault and battery. He said he had wanted to keep her as a “Key West wife” since his legal wife (in New York) refused to accompany him, but apparently the second wife resisted. (Nov. 4, 1837, Gloucester Telegraph, Gloucester, Mass.)

Released from prison at Philadelphia on June 23, 1837, the ever-enterprising Mitchell soon got a ship, a long black schooner called the Blooming Youth, and began to try to recoup his treasure, buried on an island in the Bahamas. He was stymied in this effort late in November 1837 when the captain of the Revenue Cutter Dexter captured him and his six man crew on suspicion of piracy. Mitchell was taken to Mobile, but soon released. He had been suspected of having attacked the packet ship Susquehanna near the New Jersey coast earlier, but there was no proof.

By 1838, he was operating off Key West, attacking Spanish shipping in the vicinity, smuggling slaves into the coastal areas. He visited Mobile frequently.

The June 25, 1838 Mobile newspaper said Mitchell had died as the result of a bullet wound suffered in an escape attempt from the city jail.

“Mitchell, well known about our city as ‘The Pirate,” died this morning about 6 o’clock. Several days ago, he was imprisoned for a riot, and by some means made his escape. He was retaken yesterday and bound, but whilst on his way to the prison, he managed to unloose himself. In securing him, he made resistance, and the guard was obliged to shoot him down. He died from the wound received….He was notorious for having been engaged in several acts of piracy and it was supposed that he commanded the much dreaded ‘low, black schooner’ which overhauled the Susquehanna. At the time of his escape, he held a privateering commission in the service of Texas; and his purpose was to get on board of a boat at the wharf, and to reach a vessel lying at the Balize ready for the expedition. He had several companions leagued with him.” (July 2, 1838, Charleston Courier, S.C.)

This second “death” of Mitchell was no more true than the first, as the Charleston newspaper learned to its chagrin via the next day’s paper from Mobile that the obituary was a hoax perpetrated by one of Mitchell’s friends.

“The individual [Mitchell] whom we unceremoniously shot yesterday, is still among the living. There is no death so easy as that perpetrated by a newspaper. One has but to scribble off a few words and presto! an unhappy mortal is whisked off to eternity without having time to change his clothes for the journey. We beg ‘the Pirate’s’ pardon, and hope he may live a thousand years, and each day grow a better man.

“The best of the joke is, some of our enthusiastic phrenologists applied immediately for the head of the deceased,’ reported the Mobile newspaper. The jailer received the men with some consternation, told them to wait, and relayed their request to his prisoner, Mitchell, coming back with the answer “that Mr. Mitchell had use for his head-that he was very sorry to disappoint the gentlemen-hoped that they would not take it ill for refusing such a trifling request-but as they were the first comers, he should be happy to give them the preference, when he could conveniently dispense with the use of a head.” (July 3, 1837, Charleston Courier.)

Of course, newspapers throughout the United States reprinted the story of Mitchell’s death, but very few published the story of the fact that the second death, like the first, was a hoax.

By Oct. 5, 1838, Mitchell was once again active around the Key West area, very much alive, but a bit more physically handicapped as during the Mobile riot he had managed to get one foot partially crushed, so he now walked with a lurching limp. You can’t keep a good pirate down

In late 1840, Mitchell, in a Baltimore clipper, visited the port at Savannah, Ga., and said he and his crew of five men had been at the Bahamas to look for some money he had buried on what he called “Bull Key” about 20 years’ previous. However, as he had overheard the crew resolving to kill him when they had obtained possession of the money and divide it among themselves, he had refused to point out the spot, and they had finally steered for Savannah. The crew then libelled the Blooming Youth, and imprisoned the captain for not paying their wages. (Jan. 11, 1841 Augusta, Ga., reprint of a report from Savannah, Ga., dated Dec. 23, 1840)

Soon out of jail, Mitchell zealously worked to obtain assistance to make another treasure-retrieving voyage. He avowed he was never a pirate, but a privateer, and that he had been engaged in that capacity for many years, chiefly under the authority of the Brazilian flag.

The treasure he sought to reclaim was said to be worth $7.5 million, including $75,000 in Spanish coin, and the bulk of the remainder in bar gold. Mitchell said there also was a cross of pure gold, manufactured for a church in Havana, weighing 17 pounds; a diamond as large as an egg, and two watches made for the Queen of Portugal. (Ibid.)

Mitchell offered all his hidden wealth, one half to any firm in the city if they would advance money to fit him out, and ten thousand dollars to any young men who would accompany him as companions in the voyage.

According to the Savannah article of Dec. 23, 1840, Mitchell’s “endeavors were successful: a firm in good repute, of which the senior member is a communicant of the Baptist church, and the junior a quondam Methodist preacher, (I spare their names for their reputation’s sake, although the transaction is common talk here,) has chartered a fast sailing schooner, hired a captain at seven hundred dollars a month, and prevailed on a clerk of their own (a religious man) and one or two other young men, in addition, to accompany him. In the mean time, Mitchell has joined the Methodist Church, and promises it a share of the spoils_to the amount of seventy-five thousand dollars.”

Before leaving on the voyage, he met a young French girl of 20 years, a Methodist, and married her the next day. He was about 60. The Savannah newspaper writer noted that “she has probably caught the Captain Kidd infection, and fills her imagination with dreams of luxury and wealth.”

“Mitchell is a tall man, with grey hair, and a very sinister and forbidding aspect. He has lost the sight of one eye, and is lame from an injury to one of his feet, in a conflict with a mob at Mobile.” (Ibid.)

“The chartered schooner, Magnet, sailed with seven men and Mitchell on board. Various views are entertained in relation to the enterprise. Some imagine that the old fellow is deranged, and that the whole matter will end in smoke. Others entertain serious fears that he desires to get possession of a vessel, that these men will be surprised by wretches in concealment on the key, or coasting in the vicinity, and that Savannah will never see them more. The captain goes well armed, however, for such a contingency.” (Ibid.)

The Savannah writer editorialized, “The worst aspect of the affair is the connection of church members and a church with this abandoned wretch. Admit that he be nothing worse than a privateer-yet he who takes advantage of a conflict between nations other than his own, to prey upon his fellow men, is no better-no, not a whit_than a pirate; and there is an old and true saying that ‘the partaker is as bad as the thief.’ Such circumstances afford triumphant material for those who are disposed to cavil at religious effort, and look upon professing Christians as hypocrites.”

Mitchell, the Magnet and crew returned to Savannah around Jan. 8, 1841, empty-handed, much to the consternation of the crew, and no doubt the Methodist backers as well. The captain took the Savannah to Boston, where the customs collector libelled her May 7, 1841, for forfeiture of the vessel for having been engaged in a foreign voyage while under a coasting license. (May 10, 1841 Boston Courier, United States District Court report)

“It appeared that while the vessel was lying at Savannah, the captain had been prevailed upon by Mitchell, a distinguished rover or privateer in the last war, to undertake an expedition to Cat Key, an island within the jurisdiction of a foreign power, for the purpose of digging up certain specie deposited there by Mitchell some eighteen or twenty years ago. The vessel was to receive $350 a month, and to draw a handsome proportion of the money to be exhumed.” (Ibid.)

Mitchell and the Magnet crew made several excavations and dug furiously for several days without so much as finding a single sixpence, according to the court report. Mitchell attributed the failure of the expedition to the erosion of that part of the island where he had buried the treasure. He claimed that the right spot was covered by the ocean.

The owner of the Magnet, a Mr. Lothrop of Cohasset, Mass., said the vessel had been out of his control as at the time it was under a charter party for the coasting trade, and that he neither consented nor knew of her illegal occupation. Results of the libel were not found, but the Magnet was back in business within a month after clearing Boston harbor.

As for Mitchell, he still had Methodist backers to pay back, and he seemed to have convinced them to finance yet another venture, possibly the one which failed to materialize with the Methodist Rev. Capt. Daniel De Putron, related in the Historia Obscura article “The Bizarre Case of the Wannabe Pirate.” The large schooner which was reported near the Balize in mid June 1841 may have been captained by Mitchell himself. De Putron had been waiting with his small schooner to join a larger ship when he was arrested and taken to New Orleans along with his Independence ship on suspicion of piracy. Among the possessions in De Putron’s trunk were a pirate flag and a copy of the recently published “A Pirate’s Own Book,” which ironically included a story about Mitchell’s colorful background near New Orleans.

if the top-sailed schooner that sped like the “Flying Dutchman” by the Balize indeed had Mitchell at the helm, he sailed into oblivion. Nothing more was ever published about any of his exploits after 1841, and no third obituary ever appeared. His true last anchorage is unknown.

So who was Mitchell, before he came back from the dead in 1835? He had been a privateer with a Cartagena commission, and had been associated with Jean Laffite at Grande Terre and Barataria for a time. His true nature was related in his own words to an American captain, Jacob Dunham, during Dunham’s visits in 1815 and 1816 to Old Providence Island near the Mosquito Coast of present-day Nicaragua. Mitchell believed in the War to the Death against the Spanish, and boasted that he had personally killed 87 Spaniards by 1816. In short, he was a sociopath, though he treated friends like Dunham well.

During Dunham’s first visit to Old Providence to trade goods, Mitchell invited him to dine at the home of a local planter, John Taylor, whose daughter, Sarah, was Mitchell’s “wife.” The dinner featured roast pig, poultry, and all the accompaniments, with a dish of roasted plantains used for bread as was the native custom.

“The next day, I was invited to dine on board Capt. Mitchell’s vessel. The table was elegantly furnished with silver platters, plates, knives, forks, spoons, pitchers, tumblers and with the exception of the knife-blades, every article on the table was pure silver. He showed me many valuable diamonds and large quantities of old gold and silver; and the least valuable article I saw on board his vessel was the schooner’s ballast, which consisted of brass cannon,” recalled Dunham in his autobiography, Journal of Voyages, published in 1850.

Over dinner, Mitchell told him a few months earlier [in late 1815] he had captured a small trading schooner, armed her for a privateer, and appointed a Capt. Rose to the command, to go on a cruise.

“While laying here [at Old Providence] I made up my mind to sail for New York…sell my vessel and cargo…retire to private life, thinking my means would support me. One morning, while contemplating my future enjoyments when I got settled in New York, I thought it would much disturb my mind to think that old Gonzales should boast that he had frightened Mitchell, who dared not attack him. He had sent me many saucy messages by trading vessels saying I dare not come to St. Andreas (island) to annoy him, as I had the inhabitants of Old Providence, who were afraid to resist me. These reflections so affected my mind that I immediately ordered my boat manned and went on board Rose’s vessel. I told Rose we would never leave these seas until we had made an attack on St. Andreas,” said Mitchell to Dunham.

The next day, Mitchell with Rose and 46 men sailed to attack the island, some 60 miles away, and arrived shortly after 11 at night. They found the guards sleeping and killed the soldiers, then stormed the governor’s house, where they found him still asleep in bed. The governor, along with his slaves, money and plate, were taken on board ship.

Mitchell proceeded to treat the governor politely, dining with him, feeding him the best the island had, and allowing him lots of Spanish cigars. On the 10th day after the governor’s capture, Mitchell said he gave the old man a good dinner, had a glass of wine with him, and then, not skipping a beat, told the governor he was going to hang him that afternoon.

“He laughed,” related Mitchell, “supposing it a joke, and that I had no intention of harming him. He was sitting in an armchair near the cabin door on deck, smoking a cigar, when I ordered one of the seamen to reave a yard-rope from the fore-yard, bring the end of it aft and put it round his neck. He was soon dragged from the chair to the fore-yard arm (of the ship).”

He told Dunham he let Gov. Gonzales hang for about an hour, then cut the rope and “let the old devil go adrift.”

Dunham said Mitchell should have spared the old man as he could never have done him much harm, to which Mitchell coldly replied, “I have served him the same as they will serve me when they catch me.”

This scary story starkly illustrated that Mitchell was a sociopathic killer with no remorse. Dunham managed to get along with him without incident, but noted that although Mitchell had some education and had the appearance of a gentleman, he could be “one of the greatest tyrants to exercise authority over (his men) that I have ever heard of.” Dunham related in his book that one time Mitchell scalded a ship cook to death with boiling water over a simple mistake, and when a crewman remarked that was a harsh thing to do, he shot the sailor dead.

As Dunham prepared to leave for the Mosquito Coast for more trading, Mitchell said he now was bound to New York to make his permanent residence, but needed to stop off at New Orleans first to smuggle some slaves via a pilot at the Balize. On his way, he would proceed along the Cuban coast to search for Spanish vessels to take as a last venture. His arrival at New Orleans after taking a prize would become his main claim to infamy as a very successful pirate who evaded the noose through New Orleans connections and legal shenanigans.

In early April, 1816 as Mitchell was approaching the Balize in his swift-saling Cometa privateer, the US Boxer under the direction of Capt. Porter captured the Cometa, arrested Mitchell, and sent a crew on board to take the ship and crew to New Orleans for adjudication. The Cometa was laden with treasure said to be worth from $50 to $60,000; one small basket contained an estimated $10,000 in jewelry. The captain’s cabin had a great quantity of beautiful china ware, and Mitchell’s wardrobe was extremely elegant, according to naval officer’s letter published in the July 10, 1816 American of Hanover, N.H,

The Cometa’s main gun was a 1648 dated “long tom” 12-pounder on a pivot, with five other guns, from 3 to 6 pounders, all brass.

Mitchell and his crew remained in prison in New Orleans until their piracy trial that June. During the trial, Mitchell freely admitted having killed the governor of St. Andreas, and avowed he was a privateer involved in the Venezuelan War to the Death against Spanish royalists. He claimed to have Carthagenian privateer papers, but the court thought those papers were forged. Nevertheless, Mitchell soon walked out of court a free man, ready to plunder again, thanks to his secret connection to the New Orleans Association. Mitchell happened to be commander of a fleet of privateers working for the New Orleans cartel headed by attorney Edward Livingston, and had garnered prize goods worth at least $100,000 for the association’s benefit. (“Privateersmen of the Gulf and Their Prizes” By Stanley Faye, Louisiana Historical Quarterly 22, 1939) [See more about Livingston in the Historia Obscura article “Edward Livingston: A Famous Man That Few Have Heard Of.“]

Following his piracy trial, Mitchell concerned himself with smuggling like his former partners the Laffites, but along the Lake Ponchartrain shore, rather than Barataria. In 1817, an armed force tried to take him and did shoot him in the shoulder, but he escaped. By early 1818 he was once again sailing in a small schooner around the Florida keys area, but then he decided to return to smuggling in the Barataria area, where he brought down the ire of Customs Collector Beverly Chew. In July 1818, at the Balize, Mitchell managed to steal Chew’s unguarded revenue cutter with her six brass guns, only to lose it to a US naval schooner in October of that year. Mitchell escaped again. [See more about Chew in the Historia Obscura article “Beverly Chew: The Man Behind The Curtain In Early New Orleans.”]

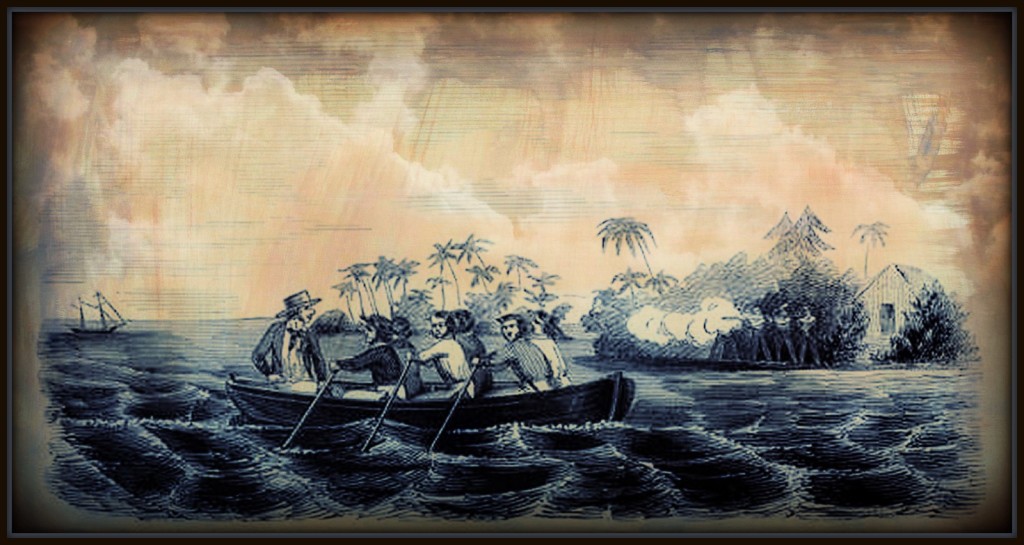

A year later, Mitchell and eight others in an armed boat were doing a series of attacks on small ships approaching the Balize, further nettling Chew and the revenue agents. Finally he tired of that and proceeded to Cuba, where he captured a schooner at Santiago de Cuba, and left to prowl around the Mosquito Coast before dropping out of sight in 1821 when his first death story appeared in the newspapers.

Mitchell had been a very lucky pirate and/or privateer in his time, with more lives than the proverbial cat. He made friends with the right people to avoid the noose, and always managed to elude full vengeance from his enemies. It was almost, one might say, like he had made a bargain with the Devil.

Recent Comments