New Book Reveals Explorer William Clark’s Dubious Past

September 17, 2016 in American History, general history, History, Louisiana History

Spying, smuggling, and possibly abetting treasonous conspirators against the United States are not actions most historians would associate with explorer William Clark of Lewis and Clark 1803-1806 Expedition fame, but a little-known 1798 journal he left behind tells a fascinating tale of an almost completely different side of the man.

“The Unknown Travels and Dubious Pursuits of William Clark” by Jo Ann Trogdon (University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2015) expertly reveals the story behind Clark’s journal of a trip he made on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers from Louisville, Ky. to New Orleans in 1798 by meticulously filling in the concise nature of his entries through research of the people with whom he associated.

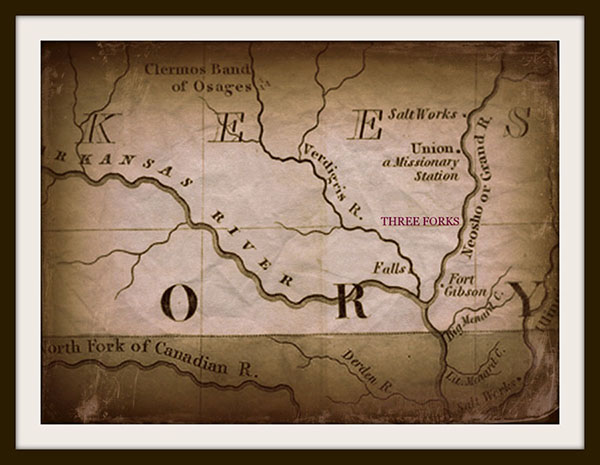

This is a tale of high adventure and smuggling duplicity on a journey Clark charted in a personal logbook which mostly stayed overlooked for some 70 years in the Missouri State Historical Society Archives at Columbia before Trogdon discovered it and began to do meticulous research in such archives as the Archivo General de Indies for the back stories of each entry in that journal. Her book is a richly told, vivid account of the political machinations and economic factors behind what was then Spanish Louisiana, and the players in the Spanish Conspiracy, the plot by traitorous General James Wilkinson and cohorts to get Kentucky and western territories to secede from the US and join Spain.

Famous for his later arduous journeys with Meriwether Lewis across the Louisiana Purchase territory and back in 1803-1806, Clark’s exploits on the lower Mississippi River show he was daring and adventurous by himself in his younger days.

This book is unique in its method of using a courtroom style procedure of point-by-point inquiry and evaluation of evidence presented through letters, documents, and journals to question what Clark’s intentions may have been during his adventure, considering foremost Clark’s almost dogged admiration for General Wilkinson, the American general who was unparalleled at planning covert missions down the Mississippi and into Spanish territory.

Trogdon’s wonderful book is a rich tapestry of life on the lower Mississippi and at New Orleans during the rule of Spanish Louisiana, and the Spanish Conspiracy which the devious General Wilkinson earnestly worked to make a reality while hiding his true colors from US authorities. Trogdon gives all the evidence and players behind the master plot. During his 1798 voyage, Clark played a role in this conspiracy by illegally smuggling Spanish silver coinage upriver to some unknown party. The extent to which Clark knew what was involved with the money, which was a payment from the Spanish to Wilkinson, is the question which is a focus of this book. Was Clark a traitor too? Perhaps. Was he a spy? Maybe. The reader is left to judge and decide.

Although all accounts are true and reported minutely, this book is not a dry-as-dust work of academia but reads more like an historical thriller, particularly in the account of how an incident at the Balisa at the mouth of the Mississippi River with Clark caught in the middle on an American ship almost made an international conflict erupt between Spain and the US.

“The Unknown Travels and Dubious Pursuits of William Clark” is that rare book that entertains and informs both the casual reader and the serious student of history, plus has everything that a professional historian could desire from such a work, particularly with the complete transcript of Clark’s logbook for comparison in the back, footnotes, a bibliography and index. An extra plus is the entertaining tracework history in the addenda about how the Clark journal wound up in the Columbia archives.

Trogdon helpfully gives back stories for all the main players in the book, to aid with fully understanding what went on in 1798. For example, in 1795, Manuel Lisa accompanied Clark from New Madrid on behalf of Wilkinson. Lisa was a courier for the governors of Spanish Louisiana territory at the time, and was trusted to carry Spain’s top-secret correspondence to Wilkinson.

Many major players involved with New Orleans business were associated with Clark, such as Daniel W. Coxe, a Philadelphia merchant, and his protégé, Virginian Beverly Chew, who would soon become a major player in the Crescent City. On the return trip to the East Coast in 1798, Clark sailed with Coxe and Chew and then traveled homeward with Chew, once they had docked. The subtle but pervasive nuances of all these interactions are multilayered. For anyone who loves historical detection, this is truly a stellar read and a worthy addition to the bookshelf for continued reference.

Recent Comments