The Meaning of Treason: United States v. Aaron Burr

February 1, 2014 in American History, general history, History, Legal History

Under the English common law, treason was an inexact and nebulous charge, one that could be leveled at almost anyone by association. Speaking against the government might be treason. Having friends who were traitors might be treason. A person might never have raised a hand in anger against his King or the state and yet still be hanged as a traitor. But under the United States constitution, treason is a well-defined and very limited offense.

Article 3, Section 3 of the United States Constitution defines and limits treason as follows:

Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.

The Congress shall have Power to declare the Punishment of Treason, but no Attainder of Treason shall work Corruption of Blood, or Forfeiture except during the Life of the Person attainted.

Notice that the word “only” is part of the definition of treason. That means that the drafters of this section of the constitution wanted a very strict construction of their words to apply. They realized that case law often adds to or changes a statutory definition, but they did not want this to happen in the case of treason. Treason was to be what they said and no less than that should ever be allowed to pass for treason in an American court, nor could the definition of treason be changed by statute or case law. Only an amendment to the constitution could ever overturn the expressed desires of those who drafted this clause.

Why did the drafters of the Constitution feel so strongly about this? Because each and every one of them, by British law, had been a traitor against Britain, long before ever they levied war against their mother country, and each of them remembered how it felt. They wanted people to be free to rise up against an oppressive government, to speak against it, censure unjust rulers and seek redress for wrongs, before it became necessary to rise up in arms.

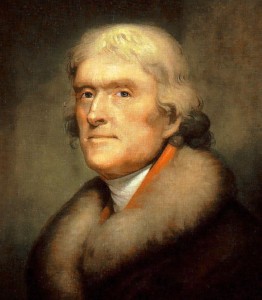

The people who wrote this section of the constitution were still alive at a time when one of their own decided to use a different definition of treason. That man was Thomas Jefferson, and he was at the time the President of the United States. He wanted Aaron Burr found guilty of treason, declared him in public to be a traitor in advance of trial by his peers, ignored the right to habeas corpus and used the military to arrest persons who were material witnesses in the trial and to hold them without access to an attorney until they had confessed.

Here is a brief factual description leading up to the case. In 1800 Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr had been tied for the presidency. They had both run on the same ticket. Eventually Jefferson had become the president, and Aaron Burr was his vice president. However, when Jefferson ran for a second term, he did not choose Aaron Burr as his running mate. Burr then devised a scheme whereby he intended to attack Mexico and acquire land in Texas. His ally in this plan was American General James Wilkinson, but Wilkinson, unbeknownst to Burr, was being paid by Spain to protect its territorial interests. In pursuance of the best interests of Spain, James Wilkinson informed Thomas Jefferson that Aaron Burr was planning to use his army against the Western territories held by the United States. Thomas Jefferson declared Aaron Burr a traitor, and he used the United States army, under the command of General Wilkinson, to arrest various people whom he believed to be aiding and abetting Aaron Burr to commit treason. Among these people were Erich Bollman and Samuel Swartwout. Although they were arrested in Louisiana Territory, they were transported to Washington City, where the president took it upon himself to personally interrogate them.

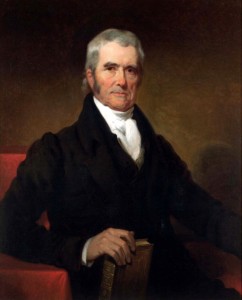

A writ of habeas corpus was eventually ruled upon by John Marshall in the case of Ex Parte Bollman and Ex Parte Swartwout. Although Bollman and Swartwout were set free for want of evidence against them and also because the Federal Court in the District of Columbia was not the Court before which they should have been brought, some of the obiter dicta in his published opinion later came to haunt John Marshall when he was presiding over the treason trial of Aaron Burr.

Namely, it was this part of the opinion that could be argued to expand the constitutional definition of treason beyond what the founders intended and to bring the American law on treason into a closer agreement with English common law:

When war is levied, all those who perform any part, however minute or however remote from the scene of action, and who are actually leagued in the general conspiracy, are traitors.

Aaron Burr had at no time levied war against the United States. Neither had any of the persons who supported his scheme to conquer Mexico and acquire land in Texas. However, at one point, on Blennerhassett’s Island, when a United States officer had come to arrest some of the men who were planning to help Burr with his conquest of Mexico, the men refused to be arrested and pointed their muskets at the poor man, who then backed down. This was the “act of levying war” on the United States that the prosecution and the Jefferson administration were basing their case on. However, when this happened, Aaron Burr had been nowhere near Blennerhassett’s Island and was not a direct participant in this “act of war”, which in fact might more accurately be described as resisting arrest.

The great legal question that had to be resolved by John Marshall in the trial of Aaron Burr was this: which definition of treason holds, the one spelled out clearly in the constitution or the one he himself had set forth in Ex Parte Bollman and Ex Parte Swartwout.

A very nice dramatization of the decision before John Marshall can be found in the video below:

John Marshall’s decision at the time was unpopular. He decided to abide by the constitution, even if it seemed that he was reversing his earlier ruling. Aaron Burr had not levied war against the United States government and no evidence that he had had been presented in court. Marshall instructed the jury on the definition of treason as set forth in the constitution, and the jury found Aaron Burr not guilty.

The Constitution of the United States is still the law of the land. Anyone charged with treason over actions not defined as treason in that document is not a traitor. This is as true today as it was in 1807.

RELATED ARTICLES

http://www.pubwages.com/14/the-character-of-aaron-burr-a-review

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CVnsnLI2I5o

http://historum.com/blogs/aya+katz/1751-gideon-granger-precursor-nsa.html

Recent Comments