The Spy Who Led the British to the Back Door of New Orleans in 1814

January 11, 2015 in American History, general history, History, Louisiana History, Nautical History

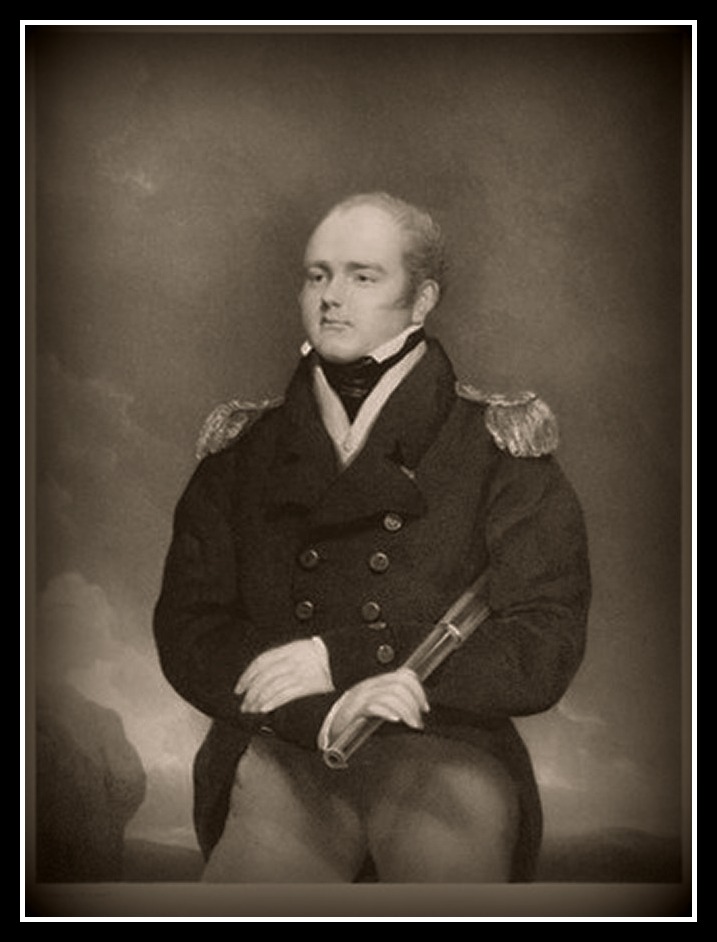

Because he was multilingual and adept at spying, the 23-year-old Capt. Robert Cavendish Spencer, an ancestor of the current British royal family, was one of the most valuable assets the British forces had during their 1814-1815 campaign to take New Orleans during the War of 1812.

“Captain Spencer (of the HMS Carron) was very usefully employed in the expedition against New Orleans. From his knowledge of the French and Spanish languages, he was selected by Sir Alexander Cochrane to obtain information respecting the state of Louisiana, and procure guides, pilots, and c. for the approaching expedition….” according to a biographical entry about Spencer in a British book (The Annual Biography and Obituary) in 1832.

After a mission to Pensacola where he barely escaped being captured by (General Andrew) Jackson’s troops on Nov. 6, 1814, and his participation in the British victory at the Battle of Lake Borgne on Dec. 14, 1814, “Captain Spencer was selected to reconnoitre Lac Borgne (sic), in company with Major (John) Peddie, for the purpose of discovering where a landing could be best effected. Having obtained considerable influence over the emigrated Spaniards and Frenchmen settled as fishermen, & c., he prevailed on one of them to take Major Peddie, himself, and coxswain in a canoe up the creek; and this party actually penetrated to the suburbs of New Orleans, and walked over the very ground afterwards taken up by General Jackson as the position for his formidable line of defense.”

Spencer was said to have bribed the fishermen to guide him and Peddie, and also received from them some clothing to disguise themselves. One thing Spencer could not disguise, though, was his bright red hair.

The two British spies walked around the Villere plantation all the way to the Mississippi River levee, whose waters mapmaker Peddie declared were “sweet and good.” Having discovered an eligible spot for the disembarkation, Spencer undertook, with Colonel Thornton, and about thirty of the 85th and 95th regiments (from the HMS Tonnant), to dislodge a strong picket of the enemy, a service which they performed most efficiently, without a shot being fired, or an alarm given.” (This included the near-capture of Gabriel Villere at his home near Villere Canal. Villere was ordered by Jackson to block the Villere Canal but had not fulfilled the order. He escaped from the British successfully, got a pirogue to cross the river to the West Bank, and proceeded from there quickly to New Orleans to alert Jackson to the British incursion. Denis de La Ronde, whose plantation adjoined Villere’s, also eluded the British and got to New Orleans safely. Latour made a successful spying excursion himself to the area of the LaCoste and Villere plantations to ascertain the strength of the British troops and judged their number to be around 1,800 men, reporting back to Jackson by 1:30 p.m. Dec. 23. The Night Battle of Dec. 2 happened later that same day when Jackson decided to attack the British encampment with ground troops aided by cannon fire from the US Carolina.)

The information about Spencer is confirmed in an 1818 obscure history of the War of 1812, A Full and Correct Account of the Military Occurrences of the Late War Between Great Britain and the United States of America, Vol. 2, by New Orleans campaign veteran William James.

“This point (Villere) had been reconnoitered since the night of the 18th (Dec.) by the honorable Captain Spencer, of the Carron, and Lieut. Peddie, of the quarter-master-general’s department. These officers, with a smuggler as their guide, had pulled up the bayou in a canoe and advanced to the high road, without seeing any person, or preparations.,” wrote James.

According to Arsene Lacarriere Latour’s Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana, fishermen and part-time smugglers living in a makeshift fishing village at the Bayou Bienvenue were responsible for guiding Spencer and Peddie to the entrance from the bayou to the Villere Canal. Once the two British officers had satisfactorily surveyed the path to the Villere plantation, they returned to lead the 85th and 95th regiments, Captain Lane’s rocketeers, one hundred men of the engineer corps, and the 4th regiment by boats from Pea Island on Lake Borgne to Bayou Bienvenue to Villere Canal. The British landed at Villere plantation by 4 a.m. on Dec. 23, at which time they rested for some hours.

American General James Wilkinson, analysing the facts in his published memoir years after General Andrew Jackson’s victory at the Battle of New Orleans, said Spencer’s guidance of the British to Villere Plantation by Dec. 22, 1814, narrowly missed being a crushing blow to Jackson.

“As the enemy had, unperceived, got within two hours’ march of the city, if they had proceeded directly forward, the advantages of General Jackson’s position, which afterwards became all important, could not have availed him, because the enemy would have carried surprise with them, would have found the American corps dispersed__without concert, and unprepared for combat; and, making the attack with a superior numerical force of disciplined troops, against a body composed chiefly of irregulars, under such circumstances, no soldier of experience will pause for a conclusion. The most heroic bravery would have proved unavailing, and the capital of Louisiana, with its millions of property, would have been lost. But, blinded by confidence, beguiled by calculations injurious to the honor of the high-mettled patriot-sons of Louisiana, and considering the game safe, they gave themselves up to security, took repose, and waited for reinforcements,” wrote Wilkinson.

In addition to his participation in the Lake Borgne battle, Spencer and the HMS Carron had been among the British warships who unsuccessfully tried to take Ft. Bowyer in September 1814, and was also involved in the successful seizure of that same fort in 1815, following the Battle of New Orleans. That seizure was declared null following ratification of the Treaty of Ghent by the United States in February 1815. For his valuable assistance, Spencer received special commendation from Cochrane and was awarded the captaincy of the HMS Cydnus in early 1815..

As younger brother of the Earl of Spencer, Prince William and Prince Harry’s direct ancestor, Robert Cavendish Spencer was the princes’ great-great-great uncle.

For related articles, see:

Capt. Percy’s Folly at Fort Bowyer

The British Visit to Laffite: a Study of Events 200 Years Later

Patterson’s Mistake: the Battle of Lake Borgne Revisited

Commemoration of a Hero: Jean Laffite and the Battle of New Orleans

Recent Comments