The British Visit to Laffite: A Study of Events 200 Years Later

August 25, 2014 in American History, general history, History, Louisiana History, Nautical History

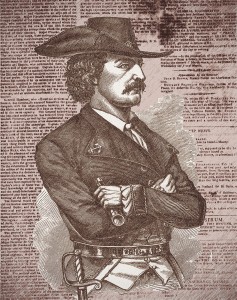

When Commander Nicholas Lockyer sailed in HMS Sophie from Pensacola towards Jean Laffite’s Grande Terre encampment on Sept. 1, 1814, he already knew that the Baratarian privateer base might soon be blown to bits, and that the Sophie would not be the instrument of that destruction, despite his written orders to that effect from his superiors. There was only a modest chance that Laffite would agree to their terms and assist the British by letting them use his light draft schooners that could navigate shallower water in the shoals. Success depended largely on how susceptible the man would be to betray his friends and clientele.

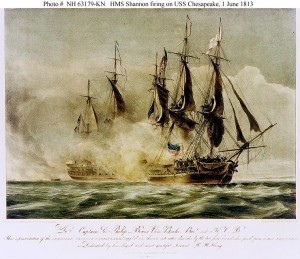

Lockyer was willing to do everything necessary to entice someone he regarded as a pirate, even though he must have felt a modicum of hesitation about approaching the buccaneers’ smuggling stronghold due to the way five Laffite-connected ships had soundly defeated British sailors of boats from HMS Herald near Cat Island and the mouth of Bayou Lafourche in June of 1813.

The Sophie by herself would be no match for the Baratarian ships. Although she carried 18 guns, her gun carriage timbers were rotten, and so shaky the carronades could not fire accurately no matter how skilled the gunners. Thus it was with more than a little trepidation on Lockyer’s part that the Sophie entered Barataria Pass that Saturday morning, Sept. 3, 1814, firing a warning shot at a privateer ship a little too close for comfort.

Jean Laffite saw a British brig in Barataria Pass, and couldn’t immediately discern the captain’s intentions as first the ship fired at one of his privateers, then the British vessel acted friendlier and non-attacking, anchoring at the opposite shore, then setting down a pinnance bearing both British colors and a white flag of truce, with some men onboard.

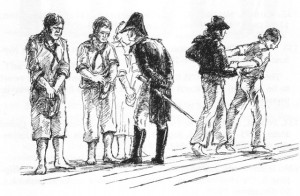

Laffite set off in his boat at once to find out who this was, and what was the meaning of this visit. As he neared the pinnance, the men’s uniforms made it clear at least two high-ranking British officers were on the boat heading to him, and so curious was he at this development that he accidentally let himself get too close to the ship, away from the safety of the shore. The British hailed him and asked to be taken to see Laffite to give him some official communications on paper. Since he was too close to the Sophie to risk being identified, Laffite told them they could find the person they wanted on shore. As soon as they were within the confines of his power, Laffite identified himself and led them to his home while close to 200 very agitated privateer crewmen milled around, voicing intentions to imprison the British and send them to New Orleans as spies. Captain Dominique You was all for seizing the British ship as retaliation for the skirmish between the Baratarians and British at Cat Island the year before, a mini-battle which the Baratarians had won, but not before the British nearly sank two of their fast schooners. Handling a visit from obvious British officers around such a group of mostly Napoleonic sympathizers was going to require finesse, but first Laffite needed to learn the precise purpose of the visit, and what the papers said.

Accompanying Capt. Lockyer was Capt. John M’Williams of the Royal Colonial Marines, most recently stationed at Pensacola. M’Williams was a special envoy from Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Nicolls, commanding officer of the Royal Colonial Marines at Pensacola,. His duty was to present official British letters to Laffite requesting that he join the British, stop harassing Spanish shipping, release any Spanish property he currently had back to its owners, and allow the British the use of his light draft ships. In return at the conclusion of the war, Laffite would receive a captaincy, land in America controlled by the British, have his rights and property protected as a British citizen, and be recompensed for the use of his ships. According to Laffite’s later recollection of the visit, the bribe also included $30,000, payable at New Orleans or Pensacola, but this was not stated in any of the British letters

An interpreter was also with the officers, but his services were not needed as Jean was fluent in English. Lockyer seized the advantage of a common language to earnestly entice Laffite to join the British against the Americans. Apparently Lockyer added the bribe money only as a spoken extra inducement to get Laffite starry-eyed about impending wealth. If Lockyer did verbally commit to a monetary bribe, there could have been little truth to it, since no one else who had helped the British in the Gulf had been paid even a tiny fraction of that amount, plus Nicolls was on a strict budget for his part of the Gulf war campaign, and could not exceed even $1,000 at the time. The only way such a bribe could have been possible is if it was to be paid after the successful conclusion of the campaign, when goods, plantations, etc., had been seized by the British, especially at New Orleans. In that event, $30,000 would have been small reward for assisting accomplishment of such a lucrative and important military goal. Regardless, the monetary bribe was worthless as it had never been commited to paper, and it was somewhat insulting for Lockyer to think Laffite was so naïve as to trust the word of even a British officer.

Lockyer pressed Laffite to join the British, especially to lay at the disposal of his Britannic Majesty the armed vessels he had at Barataria, to aid in the immediate intended attack of the fort (Fort Bowyer) at Mobile. According to Laffite’s later account of Lockyer’s manipulative spiel, he insisted much on the great advantage that would result to Laffite and his crews, and urged him “not let slip this opportunity of acquiring fortune and consideration.” Laffite cautiously demurred, saying he would require a few days to reflect upon these proposals, to which Lockyer bluntly stated “no reflection could be necessary, respecting proposals that obviously precluded hesitation, as he (Laffite) was a Frenchman, and of course now a friend to Great Britain, proscribed by the American government, exposed to infamy, and had a brother (Pierre) at that very time loaded with irons in the jail of New Orleans.” (Obviously, British spies had informed Nicolls and/or Percy about Pierre’s incarceration to use as a leverage tool with Jean.)

Lockyer also added that everything was already prepared for carrying on the war against the American government in that quarter with unusual vigor; that they (the British) were nearly sure of success, expecting to find little or no opposition from the French and Spanish population of Louisiana.

At the end of his recruitment speech to Laffite, Lockyer made a colossal error by telling what the British intended to do to absolutely guarantee success: their chief plan and crushing blow would be to foment an insurrection of the slaves, to whom they would offer freedom. In other words, the British would stir up a slave revolt resulting in brutal murders of innocent civilians at the plantations and New Orleans, given that three-fourths of the population of the New Orleans area at the time was composed of slaves.

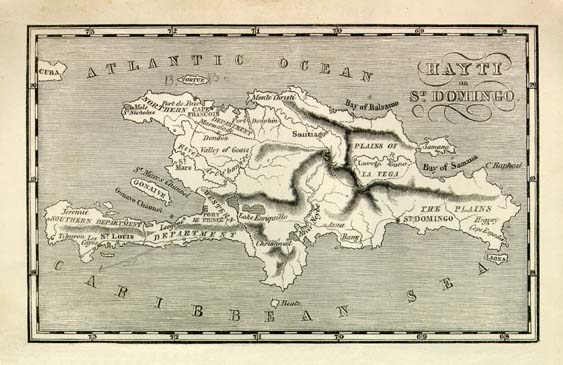

One can only imagine the disgust and horror that Laffite must have felt when he heard Lockyer say the British were going to incite (and probably arm) a slave rebellion. They were wanting him to sell out his friends and other smuggling customers and allow them to be hacked to death like the French planters on Haiti years earlier, or those families that suffered on the German Coast near New Orleans in 1811. No wonder Laffite got up and said he had to leave for a bit, leaving the British group alone snd perplexed. Laffite said in his account he left the officers because he was afraid of his privateers rising up against him, but most likely as soon as he left the house, he told his Baratarian crewmen to imprison the officers and threaten them overnight, but not to physically harm them. Laffite thought more information may have been gained by their intimidated response to the threats, that perhaps they would reveal who their spies were in the New Orleans area. He left the British alone all that night in their uncomfortable and guarded cell, even though they continually demanded to be released from custody.

Early the next morning, Laffite let the officers out of their cell, apologizing profusely for their treatment of the past night, about which he claimed he could do nothing due to the temperament of some of his men. He gave Lockyer a letter of apology in which he asked for a fortnight (15 days) to arrive at a decision about their offer, claiming the delay was necessary to send away “three persons who have alone occasioned all the disturbance” and to “put my affairs in order.”

When the British returned to the Sophie, Lockyer weighed anchor and left Barataria Pass as soon as possible around noon Sept. 4, according to the master’s logbook of the ship. They wanted nothing more to do with Laffite or the Baratarians.

Lockyer was at a loss as to how to save face re his failure to immediately enlist the Baratarians and their ships into British service. He knew Percy had ordered him “in case of refusal, to destroy to the utmost every vessel there as well as to carry destruction over the whole place,” but the Sophie by herself couldn’t do that, plus Laffite had said he couldn’t give a firm decision until a fortnight later. A fortnight later would be too late, Lockyer knew plans were already firm for an attack on Fort Bowyer before then.

The Sophie didn’t arrive back at Pensacola until Sept. 11, taking seven days, five more than necessary, to sail between Barataria Pass and Pensacola. This is odd, as Percy had requested Lockyer to return to him at Pensacola at utmost speed following the visit to Barataria. Something hidden happened in those five extra days of travel. Lockyer may have stopped somewhere along the Louisiana coast and M’Williams may have disembarked on a spy mission, as M’Williams appears not to have been with Lockyer once he returned to Pensacola. M’Williams could have gone to New Orleans, or the rest of the bayou country to reconnoiter.There is no documentation for what happened to him. The Sophie ship logs only record what transpired onboard or with the ship and its crew.

The only British account of the visit to Grande Terre was a letter written by Lockyer to Percy upon his arrival back at Pensacola on Sept. 11. Unwilling to fully admit his failure to gain the schooners quickly, Lockyer said nothing about even meeting Laffite, perfunctorily glossing over that bit entirely. Instead, in a unusually brief, terse note about the visit, he said he and the other British were immediately jailed, the British letters and order he brought to show Laffite were torn before his face plus he was insulted and had his life threatened. He wrote that the following day the Baratarians had a sudden change of mind and released them to return to the Sophie. He reported there were nine schooner privateers with six to sixteen guns each in Barataria Bay.

Lockyer’s letter was enclosed with a later report written Sept. 17 by Percy to his superior, Sir Alexander Cochrane, British commander in chief of the North America station, in which Percy says only of the letter that it acquainted him with the “ill success of his (Lockyer’s) mission (to Laffite).” Oddly, the whole Laffite issue and the matter of acquiring the light draft schooners of Barataria was dropped by Percy and became a non-issue, even though he could not have known that the Americans would destroy Barataria within a few days. Or did he know? Was there a double agent in New Orleans? What was Laffite’s reaction to the British offer?

Before Lockyer and the others had been freed from their Baratarian jail, Laffite wrote a letter Sept. 4 to his friend and Louisiana legislator Jean Blanque of New Orleans, requesting advice about what to do with the British, and enclosed all of the British papers in the packet. (All of the British papers and orders were intact, they had not been torn up like Lockyer claimed to Percy.) A courier delivered the packet by late Sept. 6 to Blanque at his home on Royal Street.

Coincidentally, that same day, Sept. 6, Dominique You, who had threatened the British officers, arrived in New Orleans. Jean’s brother, Pierre Laffite, mysteriously broke out of the Cabildo jail along with three blacks that night. Pierre had been incarcerated since July 1814 on a grand jury indictment. Dominique had been away on a cruise when this occurred, and had only returned to Barataria on Sept. 1. No one knows how Pierre broke out of jail, but both Dominique and jailer J.H. Holland were Masons, so perhaps there was some fortuitous collusion, with Holland just happening to leave the keys temporarily unguarded. At any rate, both Pierre and Dominique were back at Grande Terre within a couple of days. It seems likely Dominique saw to it that neither the British nor Claiborne could use Pierre as a bargaining chip to gain Jean’s help.

Blanque presented the letters packet the next day (Sept. 7) to Gov. Claiborne, who quickly called for an emergency meeting of his informal board of officers, consisting of Commodore Daniel T. Patterson, Col. George Ross, Customs Collector Pierre Dubourg and Jacques Villere, commander of the Louisiana militia. There was some discussion about whether or not the letters were genuine. Apparently no one thought to just hold the paper to the light to see the royal watermarks found on all British naval writing paper of the time. Claiborne worried that the letters perhaps were authentic, plus he decided from Jean’s letter to Blanque that the privateer would take no part with the British. However, he abstained from voting on what to do about the letters. Only Villere, a friend of the Laffites, and a voting member of the group, thought the British documents were genuine. Still, Claiborne vacillated about what if Villere was right.

Patterson was absolutely livid when Claiborne said it might be a good idea to postpone his planned expedition against Barataria in light of the new situation. In August, in response to myriad complaints about Baratarian smuggling against Spanish ships, Patterson had received a direct order to break up the Grande Terre base from Secretary of the Navy William Jones, who had provided him with a schooner, the USS Carolina, to accomplish the mission. A British blockade at the Balize had postponed the raid, but word had been received that British ships had moved off eastward, towards Mobile, and Patterson’s little Navy was ready to pounce. Besides, Patterson told the group his orders to attack Barataria left him no alternative but to do so, and Ross agreed. Claiborne couldn’t argue with an order from the Secretary of the Navy, even though circumstances had dramatically changed.

Ross cinched the vote by saying Laffite’s letter to Lockyer of Sept. 4 showed “Laffite’s acceptation” so for all they knew, the Baratarians were co-operating with the British. (If this were the case, it made no sense to let Blanque or the state officials see the letters, but then Patterson and Ross clearly had their minds made up before they even saw the contents of the packet or entered the governor’s chambers.) The meeting ended with Patterson and Ross announcing they would set off for Grande Terre as soon as possible. On Sept. 8, Claiborne sent copies of the packet of letters to Major General Andrew Jackson.

Meanwhile, Pierre Laffite was apprised at Grande Terre of what had transpired with the British, whereupon he wrote a letter of entreaty to Claiborne, praising the way his brother Jean had handled the situation by sending the letters to the US authorities, and saying in somewhat dramatic fashion for emphasis that he was the “stray sheep wanting to return to the fold,” offering to be of service. Claiborne didn’t get the letter until Sept. 12, and by then it was too late to stop the raid expedition.

Due to the logistics of getting the men of the 44th US infantry together, along with enough sailors, the expedition wasn’t ready to weigh anchor and go until around 1 a.m.on Sept. 11. They left in the middle of the night to ostensibly avoid spies for the Laffites, but by Sept. 13 or 14, the Laffites knew from spies that they were coming. They managed to get a portion of their goods moved to other warehouses away from the island, but a large lot remained, such as a great deal of German linen, glassware, cocoa and spices, silver plate, and some bullion specie.

The Patterson-Ross expedition took the long way to Grande Terre, down the Mississippi River to the Balize, spending nearly five days on the trip. Once at the mouth of the Mississippi, considering they had all of the American forces with them, including all of the gunboats, they could have gone to the aid of the 130 men at Fort Bowyer, but instead, they headed west, toward Grande Terre and the riches to be found there.

It is true that Patterson and Ross didn’t know Fort Bowyer was being attacked at the very moment their US expedition approaching the delta mouth of the Mississippi, but they did know from the British letters that such an attack was imminent. Luckily the men at Fort Bowyer managed to beat back a land and sea attack by the British, and were saved when the lead ship, Percy’s HMS Hermes, managed to get stuck on a sandbar. Percy was forced to set fire to his own ship and retreat. Nicolls had even worse fortune in the fray, getting ill and having to watch his Royal Colonial Marines from the supposed safety of one of the ships, only to lose the sight in one eye permanently after a stray splinter hit him.

Both Jean and Pierre Laffite managed to escape the Patterson-Ross raid that arrived the morning of Sept. 16, taking refuge at a plantation along the German Coast above New Orleans. They would remain there until sometime in mid December, when a deal would be struck with Jackson and Claiborne to provide men and supplies to assist the American forces. Captured in the raid were Dominique You and about 80 other Baratarians, who would spend nearly three months in the Cabildo jail before getting amnesty to serve under Jackson. Per Laffite’s order, Dominique made sure that none of the Baratarians at Grande Terre fired a single shot at the Americans. The raid netted five of the fast privateer schooners the British had so desired, with Patterson ordering another one, the Cometa, burned as it wasn’t ready to sail yet. Those five ships would spend several months at dock in New Orleans, and were not used to fight against the British, so effectively they had been negated. It seems odd how this played into the British scheme for Barataria. It took the men of the 44th a week to thoroughly comb through the wreckage for all the prize goods.

If Jean Laffite had decided, like Lockyer and Percy wished, to hand over the privateer schooners to the British, the first Battle of Fort Bowyer might have been won by the British, who would have proceeded from there to Baton Rouge, and down to New Orleans by the river and land, according to their campaign strategy. If Patterson and Ross had not destroyed Barataria and confiscated those privateer ships, the Baratarians could have assisted the American gunboats to rout the British warships from even approaching Lake Borgne; they also could have woven around and worried the heavy British ships from disembarking troops to attack Fort Bowyer.

The British visit to Laffite set in motion a chain of events, a domino effect, that resulted in the American victory at the Battle of New Orleans. The “what ifs’ of history are myriad: the results are what the true patriots create.

Today, almost exactly 200 years later, the area of Grande Terre where the British sat down with Laffite at his home is under the oily sludge-stained waters of an encroaching Barataria Bay. Soon, the island will be swept over into oblivion as hurricanes and time take their toll, but the memory of what happened there will live on.

FOR FURTHER READING:

Davis, William C. The Pirates Laffite, the Treacherous World of the Corsairs of the Gulf. Harcourt, 2005.

Latour, Arsene Lacarriere. Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana in 1814-15. Expanded edition, The Historic New Orleans Collection and University Press of Florida, 1999.

Recent Comments