Jean Laffite’s Curious Payment of Attorney Fees for the John Andrew Whiteman Defense

November 29, 2013 in American History, general history, Louisiana History

Jean Laffite regularly employed attorneys in the course of his business, and legal fees were a big part of his ordinary expenses. How big a part we may never know, as we don’t have access to his ledger books. He does not usually mention attorney fees in his journal, even when recounting events that involved having Edward Livingston or John Grymes represent him and his interests in court.

One exception appears on p. 151 of the Journal of Jean Laffite, in which he laments having spent $9000 on the defense of “Jn Whitman” who despite all this effort on his behalf was nevertheless found guilty and hanged on March 2, 1818.

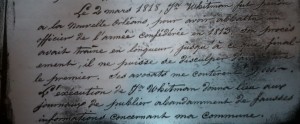

“On the second of March Jn Whitman was hanged at New Orleans for having slain an officer of the confederate [sic] army in 1813. His trial had dragged out at length, until finally he could not acquit himself of the charge of having shot first. His lawyers cost me $9,000. The execution of Jn Whitman gave the newspapers a pretext to publish extensive false information about my commune.”

Who was “Jn Whitman”? What was he hanged for? Why was Jean Laffite willing to spend a small fortune to defend him? (Nine thousand dollars in the currency of the day would be worth well over $100,000 today.) I wanted to know!

When I began investigating, the first question was what given name was the abbreviation in the journal meant to stand for. “Jn” is what Jean Laffite used in his own signature. He used it to stand for his given name, which in French was “Jean”, but could also be spelled “John” in English or “Juan” in Spanish. Later, when Laffite changed his name to Lafflin, he signed it Jn Lafflin, Jn standing for “John”. Being trilingual, it is likely that Jean Laffite used whatever version of the Biblical given name suited him at the moment, and he considered what all three names had in common to be what identified the name: starting with a J and ending with an n. It seemed reasonable that the same abbreviation was used for the name of someone in his employ, and since Whitman sounds like an English name, John Whitman was the name intended.

I consulted with Pam Keyes on this question, and she replied there was no John Whitman among Jean Laffite’s captains. There was an Andrew Whiteman who turned state’s evidence. However, in very short time Pam Keyes was able to locate this article from the April 27, 1818 Issue of the Washington Review and Examiner of Washington, PA, which told of the life, trial and hanging of Andrew Whiteman.

“New Orleans,March 4 (1818).

On Monday last the awful sentence of the law was executed on Andrew Whitman, who had been convicted before the district court of the state of shooting at one M’Key with intent to commit the crime of murder, an offence which is made capital by statute.

Whitman was a native of Philadelphia, where his connections, though not wealthy, are respectable. From the age of fifteen years, when he first went to sea in a merchant vessel, till he committed the crime for which he suffered death, his life has been a series of perilous adventures and moving accidents by flood and field. He served some time in the American squadron which in the year 1805 humbled the pirates of the Mediterranean; after receiving his discharge, he again betook himself to the merchant service, and was impressed into the British frigate La Virginie; being transferred to another vessel, he soon contrived to effect his escape to the United States. About the year 1812 he joined the piratical establishment at Barrataria, and it was under the banners of John Lafitte that he shot a custom house officer in the execution of his duty. In 1814 he deserted these his worthy associates, and betrayed Pierre Lafitte to the marshal. About this time he enlisted in the 44th United States regiment of infantry, and was in all the battles which took place during the invasion of Louisiana. Since the peace and subsequent reduction of the army, his career has been extremely vicious; his associates have commonly been the most abandoned villains who fly to New Orleans in order to escape the hand of justice at home; his residence has been in brothels and catalan shops, those sinks of iniquity and receptacles of plunder, where the experienced malefactors may find patrons and coadjutors and the uninitiated are sure to meet with prompters and instructors.

We hope that the example of Whitman will convince the gang of assassins who infest the city of New Orleans, and whose crimes cry aloud to Heaven for punishment, that Justice, though slow, is sure. and will at last assuredly overtake them, although they may triumph in their wickedness and laugh at the idea of detection; above all, we hope it will convince them that the criminal laws of the states are equally just and terrible in their inflictions, and not a mere cobweb to be evaded by the ingenious or prostrated by the powerful.”

It appears that this Andrew Whitman must be the John Whitman to whom Jean Laffite referred in his journal, and in fact the man’s full legal name was John Andrew Whiteman. But this news item raises many more questions than it answers. If Whiteman, after serving the Laffites, betrayed them and gave information that led to the capture and imprisonment of Pierre Laffite in 1814, why would Jean Laffite spend a fortune on his defense in 1818? Also, if all the Baratarians who served in the Battle of New Orleans were pardoned for any crimes committed in contravention of the Revenue Laws, why would Andrew Whiteman be tried at all for something that happened in 1813 and should have been covered by the pardon?

Could it be that because Whiteman enlisted in 44th United States regiment of infantry prior to fighting in the Battle of New Orleans, he was not eligible for President Madison’s pardon? If he had stayed loyal to his original employers, the Laffites, would he have been immune from prosecution for something that he did in 1813 while in their employ? And if he was in fact a member of the 44th regiment, was he present at the Patterson-Ross raid, on the government’s side? If so, how could Jean Laffite see his way clear to helping such a man in any way?

The answers to these questions may in fact be linked to Daniel T. Patterson’s own double dealings with the British, which are detailed in the article by Pam Keyes:

http://www.historiaobscura.com/daniel-todd-pattersons-secret-visits-to-dauphin-island-in-1814/

Could John Andrew Whiteman have known something that might have implicated Daniel T. Patterson in treason? Was he threatening to tell? Is this why the powers that be decided he must die? Is that why Jean Laffite wanted him kept away from the hangman’s noose?

The matter is currently under investigation by Pam Keyes. I am looking forward to seeing what else may be found to shed light on this mystery.

Pam Keyes said on November 29, 2013

To me, the most shocking thing about the Andrew Whiteman story is that he was executed for having fired a pistol at a customs officer: he apparently didn’t wound or kill the man. All he did was shoot at the man first, but missed him. The law in the early 1800s was quirky like that, however, for at the same time period in New York, a ship’s mate was sentenced to death for supposedly scuttling his own ship for the insurance money. That man obtained a pardon from the President shortly before he was to be executed in New York. Even bilking insurance companies was a hanging offense, it seems.

Aya Katz said on November 29, 2013

Yes, it is pretty shocking that merely shooting at the customs officer was considered a capital offense. I also had not expected that this was a matter for the state district court and not the Federal. I wonder that I have never heard of this incident nor of M’Key, as this did not seem like something newsworthy while Whiteman was still employed by the Laffites. We hear about Stout being shot, but nothing of M’Key. Was this shooting during the same confrontation as the one with Stout? And if he gave evidence before the grand jury about the same incident in the Pierre Laffite case, would Whiteman not have gotten immunity from prosecution?

Pam Keyes said on November 30, 2013

No, the M’Koy shooting happened Oct. 14, 1813, in the incident in which Randall was shot in the thigh after Walker Gilbert shot a Baratarian named Scott in the head with birdshot. Scott shot Randall. Gilbert Walker was in charge of the revenue officer’s keelboat, along with three men who seem to all have been volunteers. Whiteman fired into the cabin where an unnamed Gilbert assistant was (I guess M’Koy), without hitting him. Whiteman testified at both an 1813 hearing, and at the April 25, 1814, grand jury presentation, but this did not, for some reason, grant him immunity. He was probably threatened with imprisonment and hanging if he didn’t give a deposition. It is darkly ironic that apparently his own testimony resulted in the hangman’s noose for him.

Julia said on December 7, 2013

The harsh sentences remind me of what happens currently to drug smugglers in countries like Indonesia, who are usually foolish westerners who do not realize there is a death penalty for doing this. A few have been executed, and Shelby Corby from Australia received a fifteen year sentence for smuggling pot, even though she says someone tampered with her bag and put it there. The judges intimidated her, and kept alluding to how she would be killed by a firing squad, and was lucky to only get fifteen years.

Aya Katz said on December 7, 2013

Yes, in a way, both smuggling and dealing in drugs are victimless crimes, so I can see the analogy. In fact, you might say that drug dealing is just one of many types of smuggling. But the difference is that as far as I know, Whiteman was not hanged for smuggling per se, but for shooting at (and missing) a customs officer. Jean Laffite seems to have believed that if Whiteman could have proved the customs officer shot first, then he would not be found guilty.

Julia said on December 7, 2013

Okay, now I see.