Jean Laffite as a Father

June 16, 2013 in American History, Caribbean History, general history, Louisiana History, Texas History

According to The Journal of Jean Laffite, the famed privateer was the father of five children. He was married when he was seventeen to Christina Levine who bore him two sons and a daughter in close succession: Jean Antoine Laffite, Lucien Jean Laffite and Denise Jeanette Laffite. After Denise’s birth, Christina died, and Jean did not remarry until he was about fifty, By then his three children by Christina were grown.

Jean Laffite’s second marriage was to Emma Hortense Mortimore, and she bore him two sons: Jules Jean and Glenn Henri. But by this time Jean Laffite was in hiding and presumed dead, and he did not go by his real name in public. He may have adopted the name of John Lafflin, and his younger sons may also have gone by that name.

What sort of father was Jean Laffite? And did he treat all his children in the same way? We cannot know for sure, but there are some indications in his journal and in the few letters that were left behind.

Jean Laffite as a Single Father

From the time that Denise was a newborn until all three of his children by Christina were grown, Jean Laffite, according to the Journal that bears his name, was a widower and a single father. If he was involved with other women, he does not mention this. The journal was written for his children and grandchildren, and it was meant to be something they could pass from one generation to the next. As a member of the bourgeoisie, Jean Laffite practiced middle class morality, and he did not discuss anything that would not be appropriate to a general audience.

We know from what is written in the Journal that Denise was nursed by a black servant of her mother’s who had accompanied her to New Orleans from Port-au-Prince. Very little else is known about the early upbrining of the three children of Christina Levine.

We do know a little more about the schooling of his elder sons. Though Jean Laffite was a highly articulate man, both in person and in writing in several different languages, among them Spanish, French and English, his spelling in some of the documents bearing his signature left something to be desired. It seems that he wanted more of an education for his children, for he writes proudly of how at least one of his sons attended a language school in Washington City.

Jean Laffite as a Married Father

An oil painting by Manoel J. de Franca which is said to have been completed in 1842, depicting Emma, Jean, Glenn and Jules, when Jean Laffite was about sixty years old.

(According to Stanley Clisby Arthur in “Jean Laffite, Gentleman Rover”.

According to the Journal of Jean Laffite, following his retirement in 1823, Laffite suffered from a cold that would not go away and a rash all over his body. He was staying in the home of his friend John Mortimore, and that was when he met Emma, who helped to nurse him during his illness. It was, according to the Journal. a very real and deep love that developed between them. They married, and remained happily together for the rest of his life.

Of the two sons that Emma Mortimore bore Jean Laffite, only Jules survived to adulthood. The younger boy, Glenn, died in a freak accident in childhood. The Journal does not directly mention this death, though it is registered in the family Bible. Also, at one point in the Journal, it is mentioned that Jules is the only boy that Jean still has left at home, which would be odd if Glenn, being the younger, had matured and left home before his elder brother.

The narrator of the Journal seems averse to speaking about this loss, but there is a change of tone after the death of the younger son. Some things are too painful to write about.

Instead, at this point in the Journal, the narrator allows us to glimpse random little scenes from his family life. He tells how many teeth a certain Dr. Forbes has recently pulled from his mouth and how many teeth he has left. And he discusses the tutors of his son Jules and of his grandsons, and what subject each of them is responsible for.

The education of his son and grandsons is recorded, but the death of the youngest child is left entirely to the imagination of the reader.

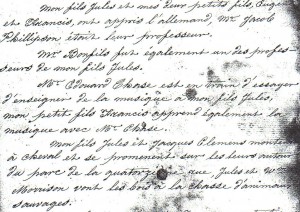

My son Jules and my two grandsons, Eugene and Francis, have learned German. Mr. Jacob Phillipson was their teacher.

Mr. Bonfils was also one of the teachers of my son Jules.

Mr. Edward Chase is in the process of trying to teach music to my son Jules. My grandson Francis is also studying music with Mr. Chase.

My son Jules and Jack Clemens go on horseback and ride in the park on 14th street. Jules and William Morrison go hunting in the woods after wild animals.

These random and somewhat disjointed accounts of Jules’ everyday life show that the father was very much interested in the education and development of the son. The two grandsons mentioned were probably the children of Denise and her husband Francis Little.

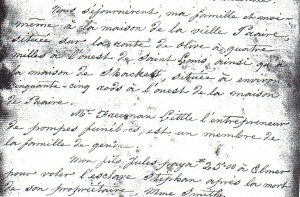

We stayed, my family and I, at the house of the old Prairie [Praire], situated on the olive Route, about four miles west of St. Louis, as well as at the house of Shackett, situated around fifty-five rods to the west of the Praire [?] house.

Mr. Freeman Little, the seller of funeral supplies, is a member of the family by marriage.

My son Jules paid $25.00 to Elmer for stealing the slave Stephen after the death of his owner, Madame Smith.

The subject of slavery is one that comes up randomly throughout the narrative. While Laffite justifies his selling of slaves captured from Spanish and English vessels, he is clearly not happy with the institution of slavery, and he seems proud of his son Jules for trying to free a slave following the death of the slave’s long term owner.

Dividing the Laffite Fortune Per Stirpes

In the passages that were quoted above, we can see that Jean Laffite was able to blend his two families, the children by his first wife, and the children by his second wife, into a harmonious whole. But it was not always that easy. When he first announced his engagement to Emma Mortimore, Denise was very much opposed to it. It was only when both she and Emma had children that Denise softened, and then she and Emma became good friends. One way in which Laffite avoided provoking envy among his children was by a wise division of his fortune among his first and second families.

There are two ways to divide an inheritance. One is per capita — by the head — and the other is per stirpes — by the stock.

People who tend to divide all their property among their heirs equally tend to disregard that some heirs have many children and others have few, and they tend to favor those persons in their family who left many offspring. But a fairer distribution is by the stock, acknowledging the different lines, and treating each progenitor equally, regardless of how many children they had. In most cases, the division takes place after death. But when Jean Laffite retired, he took all his property and divided it into two parts: one part for the children of Christina Levine and the other part for himself and his new wife and young minor children. He distributed the first half equally among Antoine, Lucien and Denise. The second half he kept to live on, and eventually leave to his current wife and her children.

In this way, Jean Laffite honored both of his wives and dealt fairly with each of his children. In the Laffite family, there was no quarreling over inheritance. All were well provided for.

REFERENCES

The Journal of Jean Laffite, a manuscript currently housed at Sam Houston Regional Library and Research Center, Liberty, Texas.

Arthur, Stanley Clisby. 1952 Jean Laffite Gentleman Rover. New Orleans: Harmanson.

J-Hanna said on June 16, 2013

Jean Laffite not being the best speller in the world was quite common for the time period he lived in. Andrew Jackson also spelled many of the same words different ways, and American spelling of the English language was not standardized until Webster came out with his dictionary. When I was reading first hand documents of Captain Bligh and Fryer from Mutiny on the Bounty fame, they also had issues with spelling, and were considered very educated men for their time period. I think Jean Laffite sounds like an interesting man and father.

Aya Katz said on June 16, 2013

Yes, Julia, I think you are right. It was quite common for men with a certain amount of education to be unable to spell consistently, and it may be due in part to a lack of standardization. Andrew Jackson came from a less than privileged background and had to struggle for his education. But I must also note that Aaron Burr, who was a classics scholar, was constantly correcting Theodosia’s spelling in her letters, so there must have been some standards. When Jean Laffite spelled sentiment with a “c”, I think that went beyond ordinary fluctuations in accepted spelling, as it implied stemming from a completely different root — one hundred instead of feeling. This is not a mistake a well educated Frehch speaker would be expected to make.

I think there was a class distinction involved here, with the poorer spellers betraying their ignorance of the classics and grammar, not just a question of memorizing arbitrary spellings. That’s why in my novel I had Theodosia mortified by the mistakes Jean made in his letter to President Madison.

J-Hanna said on June 17, 2013

I think among the highly educated there were more standards, but consistency was not abundant. In Britain, Fryer studied the classics, and was considered quite educated, but his spelling was not the most consistent. However, he was probably not as educated as say Burr. I have read quite a bit about the history of the dictionary, and the reason it was created is because there was such a great disparity with spelling words various ways. Even paragraph writing as we know it today did not really become consistent in books until the 1850’s.

Aya Katz said on June 17, 2013

I tend to agree, Julia. There were degrees of education, and Burr was unusual in his erudition. Even so, many things were not standardized until much later, and, of course, some of the spelling conventions changed in the process.

Stephen Formel said on December 13, 2013

Spelling in those days was all over the park. William Clark (of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Corps of Discovery) spelled the SOUIX Indian tribe thirteen (13) different ways!

Governor said on December 13, 2013

Well, at least Sioux is not an English word and was a recent borrowing from Algonquian Nadoüessioüak into French in the 17th century. That’s not at all the same as English words borrowed from Norman French and standardized much earlier.