Beverly Chew at the height of his power in New Orleans

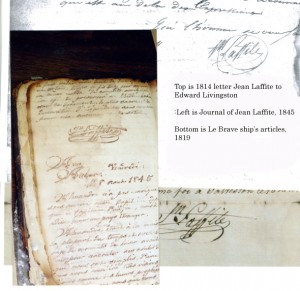

Life was good for the New Orleans business firm of Chew & Relf in the early 1800s: young partners Beverly Chew and Richard Relf controlled a virtual monopoly of the banking, shipping, trading, insurance, and smuggling business in the port city until around 1809, when the Laffite brothers came to town, quickly and systematically cutting into the profits of Chew & Relf’s Gulf Coast network empire.

Jean and Pierre Laffite successfully snatched away the market share of the smuggling business from Chew, Relf and their cohorts Daniel Clark, mainly because since they were getting their goods and slaves from privateers’ captured Spanish prizes, they paid nothing for their wares and consequently could sell them much cheaper because there was no middleman to pay.

The Laffites made an enemy for life of Chew in particular, and he would strike back like a snake when a prime opportunity presented itself eight years later. He wielded much more power in New Orleans than most people realized, and could carry a grudge for years. Along with his partner and other backers, he controlled business in the city for more than 30 years in the early 1800s. Through study of his business connections, deals, and political machinations it is evident that Chew, not Edward Livingston as commonly supposed, was the true power monger behind the curtain of New Orleans, with the help of Relf. Moreover, Chew stayed at the top of the exclusive business elite in New Orleans through the 1830s.

Historian John G. Clark said “The elite which emerged in New Orleans between 1803 and the War of 1812 possessed power and responsibilities unprecedented in the almost 100-year existence of the city.’ (The Business Elite of New Orleans Before 1815)

Born in Virginia in 1773, Chew moved to New Orleans in 1797 from Philadelphia, where he had been an apprentice for prominent merchant Daniel William Coxe and associates, and also had learned financial finagling from Natchez plantation owner William Dunbar, who had traded cotton through Coxe.

According to historian Arthur H. DeRosier Jr., Dunbar used Chew and Relf in the early 1800s to ship bales of cotton through New Orleans, for pre-negotiated prices to Liverpool, seldom taking specie alone for the transactions. Every shipment of cotton included a list of goods Dunbar wanted, which Dunbar would resell for more in the American markets. He floated the real money (gold and silver specie) like so many chess pieces among his agents to make purchases as needed, or to stall payment until goods were delivered from England. Knowing exactly where all the specie, cotton, and goods were took a very careful system of bookkeeping, which Dunbar did well. His protégé, Chew, implemented this system himself upon Dunbar’s death in 1810. (William Dunbar: Scientific Pioneer of the Old Southwest)

Chew and Relf both came to Louisiana about the same time shortly before the turn of the 19th century, in league with the well-known Irish land speculator and businessman Daniel Clark, believed to be one of the wealthiest men in America, and the notorious double-dealing General James Wilkinson, who often was complicit with Spanish authorities.

Chew counted among his personal and confidential close friends the adventurer Philip Nolan, clandestine agent of Wilkinson re Spanish land grant schemes in Louisiana territory. In 1797, before moving to New Orleans, Chew wrote Nolan that he could draw from the Spanish king’s coffers at New Orleans any sum he would have named on account of the General, and it was reported and pretty generally credited then that Nolan had indeed received as much as $5,000. In 1798, Chew wrote to Nolan that he was departing on a voyage to Bilbao, Spain, saying “respecting the connection we have so long contemplated, you will find my wishes for it undiminished, and will be able to make it much more advantageous on my part than when I last saw you.” Details about Chew’s dealings with the Spanish authorities have not been found.

In mid 1804, as President Thomas Jefferson sought input about who to recommend for positions in New Orleans, an unknown letter writer advised that “Beverly Chew of Virginia, connected with M.D. Clark, is a man of very respectable standing and most deservedly so_He loves his Country and is a zealot in its support__He has served Gov. Claiborne essentially.” One wonders if the writer happened to know that Jefferson was a distant cousin of Chew’s. Chew also was a kinsman of Mississippi territorial governor William C. C. Claiborne. Letters of the late 1700s and early 1800s between Jefferson, Coxe, and Dunbar make it look like Jefferson was at least partially responsible for placing Chew in New Orleans to assist Claiborne and learn about Spanish and French plans for the port city.

Claiborne named Chew a justice of the Court of Common Pleas at New Orleans in 1805, and a short time later, appointed him as first postmaster of New Orleans, a temporary position of a few months. This came after an incident in 1803 when the New Orleans City Council had barred Chew and Relf from importing West Indian slaves into the US, largely because when his own slaves were arrested for theft of some whiskey and tobacco from someone named Bond, Chew had admitted in court to accompanying the slaves that night. In 1805, Chew simply skirted the law by having slaves smuggled up the Bayou LaFourche to be sold there, out of the court’s jurisdiction. The Laffites would later use the same bayou to transport both slaves and goods for smuggling into New Orleans, and may have studied the methods Chew had earlier employed.

“The firm of Chew & Relf …engaged in enterprises that circumvented the law. After the importation of African slaves was outlawed by federal law in 1808, they often acted as middlemen for other firms, some as distant as Charleston, S.C., that wished to import slaves….They used their business contacts with Spanish officials in West Florida to facilitate the landing of slave ships and the distribution of their cargoes at Mobile,” according to Junius P. Rodriguez, in The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia.

Chew counted among his close business associates John Forbes of West Florida, an internationally known trader of long-standing with the British. Forbes was a loyalist who had been with the well-entrenched West Florida frontier firm of Panton, Leslie & Co., earlier. He sold mostly trade goods which came from Britain, including guns, lead and gunpowder. He had a post at Mobile, from which goods could be sold to avoid the New Orleans duties. He was associated with Chew as both a personal friend and merchant through at least 1816.

Despite their often illegal smuggling and other questionable business activities, Chew and Relf never were charged with any crimes as they had their hands in almost every major New Orleans business: they were originators, original shareholders, and members of the board of directors of the New Orleans Insurance Co., insuring vessels, cargoes and specie. Plus they were exclusive agents of the London-based Phoenix Fire Insurance Co. Banking interests formed a major part of their portfolios: Chew was on the board of directors of the Bank of the United States New Orleans branch as well as major stockholder of the Bank of Louisiana. Additionally, in 1805, Chew was on the board of directors of the US Bank of Philadelphia branch at New Orleans along with his good friend Thomas Callender.

Chew and Relf had started their New Orleans Anglo-American empire quite early, in 1801, when they joined with land speculator and business dynamo Clark. They dealt in goods for Reed and Forde of Philadelphia, freighted and leased vessels to St. Domingue, Bordeaux and London; received English goods on consignment, and bought and sold staples and groceries on their own account. In one deal, William Dunbar forwarded 3,000 pounds sterling in notes on London endorsed by Chew and Relf to a Charleston, S.C. slave trader as half down, with the balance paid to Chew and Relf. They had a store on St. Louis Street, between Royal and Chartres streets, which served as a “one-stop” shop for a myriad of needs.

According to historian Ernest Obadele-starks in Freebooters and Smugglers: The Foreign Slave Trade in the United States, “Chew and Relf were part of a solidly entrenched business circle that dominated the town (New Orleans) politically, set its social tempo, and controlled economic development by legal, extralegal or illicit means.”

Chew’s British business connections remained solid through all of the War of 1812, but oddly no one in New Orleans ever questioned his loyalties. When almost every other trader was financially hard hit by embargoes and British blockades of US seaports, Chew & Relf did not suffer major losses, not even when their financial backer, Daniel Clark, unexpectedly died in 1813.

In 1810, Chew had increased his political power in the city by marrying Maria Theodore Duer, a relative of the immensely powerful Livingston family of New York, and a cousin to Edward Livingston of New Orleans.

President James Madison appointed Chew as vice consul for Russia at New Orleans in July, 1812, to handle commercial reciprocity between US and Russia since Russia was said to take a favorable view of the American effort to defend neutral shipping rights. Madison either overlooked or was unaware of Chew’s ties to British concerns.

Sensing that the war between the US and England might prove problematic to his business interests, Chew tried to hedge his bets by pushing westward with land speculation in Louisiana. Rapides Parish records files of Oct. 24, 1812, show that Beverly Chew claimed a tract of four hundred acres of land on the left bank of Bayou Rapides, sold to him by a man named Fulton, with the land having been inhabited and cultivated as required by law of the time. No records are available regarding what use Chew made of this property, nor if he later sold it to someone else.

In the summer of 1813, and while his backer Clark was ill, Chew decided to make a trip back east to visit relatives and business concerns in the Philadelphia and Virginia areas. On July 24, 1813, Chew, his wife, and their daughter arrived at Philadelphia from New Orleans on board the brig Astra, making the voyage following a stop in Havana in only eight days. They passed the British blockading squadron around the Cape Henlopen side, without incident as the ship was in ballast.

While Chew was gone from New Orleans, Relf took care of Clark, who died suddenly after appearing to be getting better. A second will which Clark had made disappeared immediately after his death, leaving his original 1811 will, which named Chew and Relf as his co-executors. Clark’s mother, Mary, was named sole inheritor in the original will, but she never received a penny of the estate. Chew and Relf claimed after paying debts and expenses due to wartime, there was no money left, but their business did not suffer any such losses, and no formal accounting of the estate expenses was ever made. The second, missing, will had named different executors and had given a major bequest to Daniel’s sole heir, a daughter named Myra. The controversy over the Clark estate and what happened to all the money would be the focus of an extended and famous Supreme Court battle waged by the Clark daughter, Myra Clark Gaines, in later years.

During the British invasion of Louisiana in 1814-1815 and subsequent Battle of New Orleans, Chew served as a volunteer rifleman under General Andrew Jackson in Beale’s Rifles.

In late 1816, Chew was appointed customs collector for the Mississippi River port at New Orleans following the resignation of P.L. B. Duplessis. He set to his new role with a special fervor against smuggling interests other than the ones which boosted his own bottom line.

Chew must have felt elated in August 1817 that finally he could do something to strike back at the Laffite brothers, considering they had interfered with his business concens for years in the New Orleans and Gulf Coast area. Now that they had set up a privateering enterprise just outside US territory at Galveston, Chew saw a way to convince Secretary of Treasury William H. Crawford to get rid of the Laffite threat to commercial shipping heading to and from New Orleans.

The customs collector felt confidant he could sway Washington politicos to his wishes because for several years, he had been the top leader among the handful of business elite that controlled New Orleans and all the trade that plied the Gulf Coast of Louisiana. His new role as customs collector was only the tip of the iceberg in terms of what he manipulated directly or indirectly through banking, insurance, shipping, and trade interests.

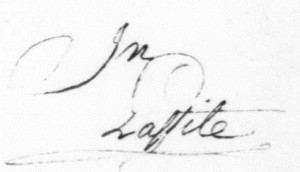

In his lengthy letter to Crawford of August 1817, Chew pointed out, “I deem it my duty to state that the most shameful violations of the slave act, as well as our revenue laws, continue to be practiced, with impunity, by a motley mixture of freebooters and smugglers, at Galveston, under the Mexican flag; and being, in reality, little else than the re-establishment of the Barrataria (sic) band, removed somewhat more out of the reach of justice.…Among the most conspicuous characters…at Galveston, were many of the notorious offenders against our laws, who had so lately been indulged with a remission of the punishment, who so far from gratefully availing themselves of the lenity of the government to return to, or commence an orderly and honest life, seem to have regarded its indulgence almost as an encouragement to the renewal of their offences. You will readily perceive I allude to the Baratarians, among whom the Lafittes may be classed foremost, and most actively engaged in the Galveston trade, and owners of several cruisers under the Mexican flag. Many of our citizens are equally guilty, and are universally known to be owners of the same kind of vessels.”

(The Baratarians had been given presidential pardons for their aid and service to General Andrew Jackson in the concluding battles of the War of 1812, culminating with the Jan. 8, 1815, Battle of New Orleans, a decisive victory against the British forces, due in no small part to the skill of the Baratarian gunners and the flints and powder provided by the Laffites.)

Chew proceeded to go on at length about the supposed crimes and revenue avoidance perpetrated by the Galveston parties, which is ironic, as it is a case of the pot calling the kettle black. No one in Washington knew it, but Chew himself had long been a very successful coordinator of smuggling slaves and goods in the New Orleans area, West Florida territory, and southern seaboard. He had started early: between 1804 and 1807, he and his longtime business partner Relf had sold around 430 slaves, many of which were obtained via illegal channels. Almost all had been smuggled.

As a customs agent, Chew benefitted from the fees collected at customs, while at the same time he also participated in his own smuggling operations. He frequently overlooked slave importations any time he could profit personally. Although he ordered that all ships arriving from the Laffites’ base at Galveston be searched, it was not because they were importing goods into New Orleans, but because he suspected that they were not authorized by the Mexican government as privateers. Without a valid letter of marque or commission, the ship and cargoes could be seized by the customs agents, and Chew, of course, would profit.

Secretary of Treasury William Crawford outlined specific instructions for the conduct of US revenue officers which Chew zealously overstepped whenever it suited him. Crawford wrote “While I recommend, in the strongest terms, to the respective officers, activity, vigilance, and firmness, I feel no less solicitude that their department may be marked in prudence, moderation and good temper. Upon these last qualities, not less than the former, must depend the success, usefulness, and consequently, the continuance of the establishment, in which they are included. They will always remember to keep in mind, that their countrymen are freemen and, as such, are impatient of every thing that bears the mark of the domineering spirit. They will, therefore, refrain, with the most guarded circumspection, from whatever has the semblance of haughtiness, rudeness, or insult…They will endeavor to overcome difficulties, if any are experienced, by a cool and temperate perserverance in their duty__by address and moderation rather than by vehemence or violence.” Crawford’s express intent that smugglers be treated in a gentlemanly manner was blithely ignored by Chew.

Chew’s series of letters to Crawford about the Laffite problem at Galveston went on to discussion at Washington, with Congress reviewing documents in January 1818 consisting mostly of Chew’s complaints about Jean Laffite’s occupation of Galveston Island and how he was using it as a base to launch attacks against shipping in the Gulf of Mexico, plus the “pirates” were engaged in smuggling slaves into the United States. John Quincy Adams followed Chew’s invective avidly, agreeing that after Louis Aury left, Galveston became, “indisputedly” piratical in nature. Adams further went on to publish diatribes in the press under his pen name Phocion in which he called Galveston an “association of adventurers, renegades and desperadoes from the four corners of the earth, whose sole aim was the indiscriminate plunder of commercial shipping.” Adams asserted the right of the US to “constitute itself the protector of its own seas and protest the renewal of the scenes of horror such as when ‘Lafitte’ held Barataria.”

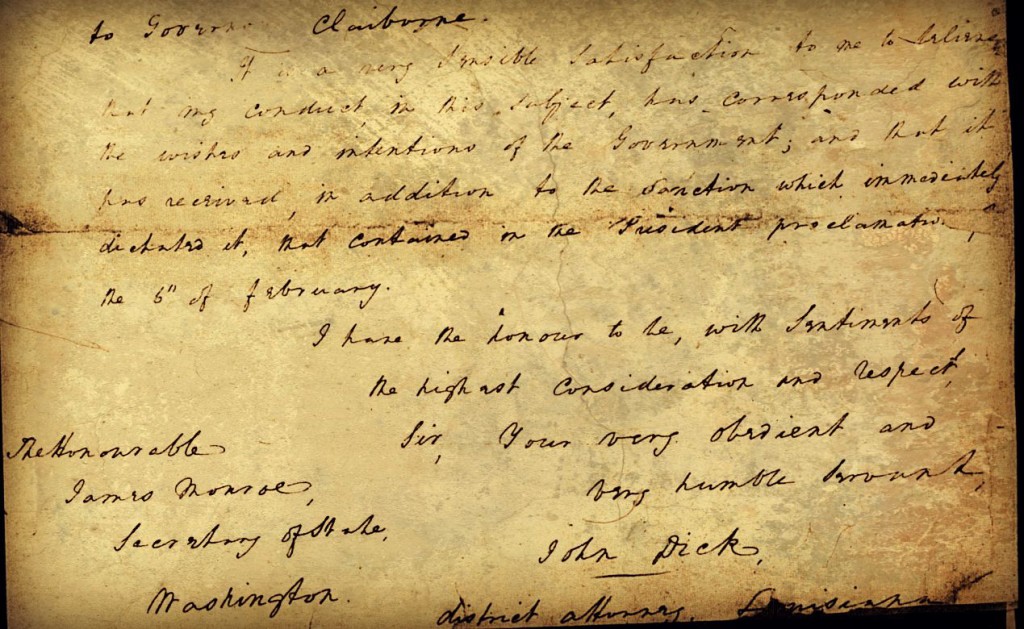

Monroe came out with a presidential proclamation about Galveston and Aury’s new base at Amelia Island, but he repeatedly suspended orders to seize Galveston, which must have made Chew apoplectic with anger.

When US authorities finally did move against Galveston in early 1820, it was not with warships, but diplomacy through Commodore Daniel T. Patterson of New Orleans, with encouragement to end the privateering establishment there. Beset by turmoils within and without Galveston from others, the Laffites left voluntarily, with a safe conduct pass from Patterson. They didn’t leave because the US wanted them to go: they went because privateering was becoming much less profitable and the captains who served them were turning more unmanageable.

Chew’s friends back in New Orleans, however, took the news as a sign of their custom agent’s political clout to get things done. Even two years later, in 1822, his friends were still crowing about how Chew had almost single-handedly vanquished Galveston, as evidenced in this editorial in the Louisiana Advertiser:

“The banditti who infested Galvestown (sic), and the coast of Western Louisiana have been driven away by the vigilance of our officers and, we do not believe, there is at this moment a piratical rendezvous from the Cape of Florida to the Isthmus of Darien…They have been totally expelled from the American shore by the vigilance of our collector, his subordinate officers, and our small naval force. As resulting from the prostration of the ancient system of smuggling and the breaking up of the haunts of the villains who were engaged in it, the principles of an honourable and legitimate commerce begin to flourish. We have thus traced the progress of this improvement in our character, and amelioration of our commercial morality; and for their instrumentality in producing such results we openly affirm that Beverly Chew, and the officers under the control of his department, are eminently entitled to the lasting gratitude of the citizens of New Orleans, and of every honest inhabitant of the Gulf of Mexico.”

Chew did not stop engaging in illegal activities just because he had become a well-respected port collector. According to Obadele-starks, “In June 1824 Chew authorized the ship Ceres to enter New Orleans with slaves despite the fact its crew presented no manifest. In 1825, he informed the New Orleans major of his intent to allow a free African family from Port au Prince into Louisiana although they lacked the legal documents to enter the country.” Additionally, Chew turned a blind eye to some other slave cargoes in that time, especially when the owners were friends and fellow church members of his.

Chew had served as collector for over 12 years when new President Andrew Jackson refused to re-appoint him, naming another New Orleanian in his place in 1829. Jackson’s chief of surgery during the campaign against the British, New Orleans physician Dr. David C. Kerr, recalled that “So virulent was Chew in his opposition to Jackson, that he even refused permission to hoist a flag on the church of which he was vestryman or to have bells rung on the 8th of January” in honor of Jackson’s great victory. The antipathy between the men could possibly be explained by the fact that in 1828 while still customs collector, Chew had been unanimously elected president of the United States Bank of New Orleans. Jackson was extremely opposed to the US Bank.

Even though Chew was employed as a bank president after his dismissal, his cronies lamented Jackson’s cruelty in casting him aside in his old age. According to the May 18, 1829 issue of the Courrier de la Louisiane, a group of Chew’s friends gathered together at the Exchange Coffeehouse to express their “regrets at the removal of that gentleman as collector” with Thomas Urquhart acting as chairman and John Hagan, secretary. They lauded Chew to the highest degree, saying he was a skillful, able and efficient officer as collector at the port of New Orleans; that he always had at heart the interest of the government, and the punctual observance of the laws; and that he had endeared himself to the public by his constant and strict attention to these interests; and by his gentlemanly deportment.

The friends said “we sympathize with him that after so many years devoted to the public service, he retires into private life without fortune, and with a large family, dependent upon everyone, that at his late period of life, must find new channels, through which to earn them a support,” and agreed to gather subscriptions from the public sufficient to offer Chew a suitable present upon which shall be inscribed “what their hearts may dictate as our feeling and their judgment.”

Chew stayed in the banking industry, resigning from the Second Bank of the U.S. to become cashier of Canal and Banking Co. of Louisiana in 1831. A year later, in 1832, he assumed the presidency of that financial institution.

He still kept his old ways about meddling in land speculation while he had some money and power, as in 1836, he was a member of the Texas filibusters group called the Native American Association, involved in the Texas revolution to seize lands from Spain.

From 1834 until the end of his life, in 1851, Chew would be plagued with lawsuits and trials over the Daniel Clark will and the unsettled rights of Daniel’s daughter, Myra Clark Gaines, to her inheritance. The tangle of legal testimony and lawyers would reach all the way to the Supreme Court and become one of the longest running cases in history (it ended in 1891), but neither Chew nor Relf would ever present a word of testimony in court, letting their attorneys handle it all.

The collective attorney fees and court expenses ate through whatever financial gains Chew had had, so that by his death, he had hardly anything in his estate to leave his heirs. Probate records show that Chew died with no funds to afford his children a “liberal education,” and advised them to sell ten lots of land in Lafayette, Jefferson Parish. The land speculator who had once held the purse-strings of New Orleans and ruled the city’s business for over 30 years died virtually broke.

In a coda to this story, Chew’s remains are not still at rest in the Girod Street Cemetery in New Orleans where he was entombed. Due to severe vandalism, in 1957 that cemetery was deconsecrated and all the remains were relocated in an anonymous mass tomb at Hope Mausoleum in New Orleans. The site of Chew’s first tomb is now beneath the Superdome parking garage.

Recent Comments