The Saga of Melita and the Patterson-Ross Raid at Barataria

December 15, 2014 in American History, general history, History, Louisiana History, Nautical History

A series of unfortunate events plagued Joseph Martinot, supercargo of the Carthagenian merchant schooner Melita. First, he had been stymied in his attempt to enter the Mississippi and arrive at New Orleans by the presence of the British blockade near the Balize; then, off the coast of Louisiana to the westward of the Balize, he had been caught in a storm while trying to slip by the British: his ship had been damaged by the squall, so he made for the closest place for repairs, which happened to be Jean Laffite’s smuggling base at Grande Terre; next, he had endured hassles trying to lawfully bring his goods to New Orleans, and now, back at Grande Terre to oversee ship repairs, he found himself fleeing for his life in a pirogue paddled by frantic Baratarians as men on a US Navy barge fired musketry and an occasional cannon shot their way.

The Navy barge soon closed the distance between the vessels, and Martinot found his lot cast in with Dominique You and the Baratarians in the Sept. 16, 1814, raid of Grande Terre by Commodore Daniel T. Patterson of the New Orleans Naval Station and Col. George Ross of the 44th US Infantry.

At least, thought Martinot, he had covered himself by declaring his goods and paying the appropriate duties at the New Orleans customhouse some days earlier. There was proof of that with Notary John Lynd in town, so he believed Patterson would treat him with the appropriate consideration. Martinot and his ship had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time. Patterson and company, however, did not see it that way.

Martinot and the others were conducted onboard the gunboat of Comm. Patterson, who made the supercargo open a trunk he had taken with him in his flight from the raid. Then Patterson somewhat belligerently searched through the trunk himself, confiscated a telescope and a poignard (type of Spanish knife) , then directed Acting Lieut. Isaac McKeever, to proceed with a modified strip search of Martinot.

According to Martinot’s later deposition to Lynd, he took off his vest and laid it on the deck of the gunboat, then opened his pantaloons, and McKeever raised up the supercargo’s shirt to see whether he had any money or valuables concealed on his person, but none were found. Then Martinot was ordered to take off his boots, and they too were searched, with nothing found concealed in them, either. Frustrated in their endeavors to find valuables, Patterson then went through the pockets of the vest which was on the deck, and in the corner of a handkerchief he probably smiled as he pulled out a folded batch of bank notes, which must have made him quite happy, considering there was a total of $700, or the equivalent of over $9,000 in today’s currency. Martinot had been carrying a small fortune in that vest.

Patterson demanded that Martinot tell him how much money was in the handkerchief, to which the supercargo replied he did not know, so Patterson proceeded to count out the notes and told Martinot to count the amount as well. Martinot thought this demonstration might mean he would get the money returned to him as his own property over which they (the naval authorities) had no right, and said the same to Patterson, whereupon McKeever likely laughed as he said there was little chance of the prisoner recovering it. Patterson would not give him a receipt, just told Martinot brusquely to see him at his office in New Orleans later.

Alarmed at the loss of his money, Martinot explained the nature of his business at Grande Terre, and that he had been there but two days, repairing his vessel (the Melita), and pointed out the ship which was moored to the shore as she had been half full of water and had only recently been pumped out dry to start repairs. Martinot continued by saying the Melita had been regularly reported to the customhouse, and the duties of her cargo paid, that he had brought provisions for her repairs from town, and had deposited them in Msr. Lafitte’s (sic) store, with the ship’s rigging, sails, anchor, cables, and five barrels of bread. Patterson turned a deaf ear to Martinot’s account.

Worse was to come for Martinot. On the evening previous to his departure from Grande Terre, Patterson demanded of Martinot a list of the sails, and said he had no knowledge of any other articles. Then the next day shortly before he left (and after the officers and soldiers had thoroughly scavenged and retrieved anything of value on the island), the commander ordered the dry-docked schooner burned. Martinot was allowed to go on shore to see if he could find anything belonging to his ship, but of course nothing was left to find.

Patterson and Ross, with their men, had claimed and seized all the “booty” and ships that they could, and destroyed the rest. All told, they had seized close to half a million dollars’ worth in the raid.

Martinot was not jailed for very long, as by Sept. 29, he was back in the office of Notary John Lynd, deposing his protest against “Commodore Patterson, his officers, and all others who may concern (sic) for the loss and damage done by him and them, or by his order to the said vessel (Melita) and her stores and materials, for the value of which he holds him and them responsible, and which he will endeavor to recover of him or them by all lawful ways and means.” Records show that Martinot did pursue them in the court system, but due to rapidly transpiring events with the British invasion, nothing was resolved, and although Patterson told him to see him at his office for a recipt for the $700, etc., that, too, must not have transpired, considering Martinot filed the protest. The man’s telescope must have remained part of Patterson’s seizures, too, and it was a valuable instrument in itself.

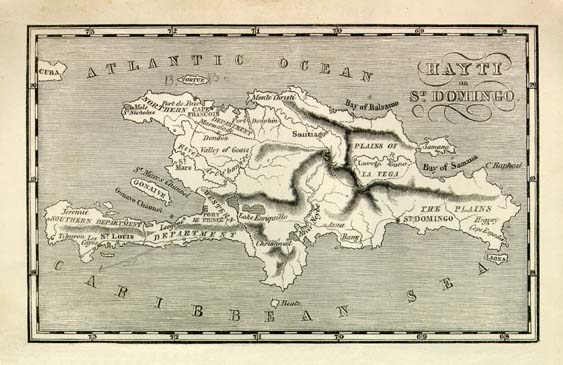

The saga of the Melita’s and Martinot’s troubles began in July 9, 1814, when the schooner left Cartagena bound for New Orleans. During the voyage, as well as previous to their departure, the master and supercargo of the Melita were repeatedly warned by various captains of other ships in the Gulf not to attempt to enter the Mississippi River by way of the Balize as they would run a great risk of being captured by the British warships blockading off the bar there. The Carthagenian privateer General Bolivar , owned by Laffite associate Renato Beluche, had recently attempted to enter the Balize only to be chased off by the British.

Martinot said in his testimony to Lynd in a sea protest filed August 4, 1814, that due to the warnings about the British, they therefore endeavored to fall in with Grande Terre, to westward of the Balize, and came to anchor on the coast in five fathoms of water: while there, a storm arrived from the south so heavy that it parted their cable, and they lost part of it along with the anchor. The ship limped to Grande Terre, where Martinot in his role of supercargo took the goods off the ship, loaded them on some pirogues, and proceeded up the bayous to the Customhouse at New Orleans to make a good faith declaration to the Revenue Department so that even though the Melita could not arrive at New Orleans the regular way, her cargo would be lawfully entered at the port.

Martinot made sure to attest that it was only due to fear of the superior force of the British off the Balize that the Melita had diverted to Grande Terre, where she went by necessity, and self-preservation, and not any sinister view, nor intent to defraud the revenue of the United States.

Accordingly, P.L. Dubourg, clerk of the New Orleans Customhouse, then gave Martinot written permission on August 5 to bring the goods, consisting of four trunks and fourteen boxes of dry goods, marked “Mt” through the lakes to the landing opposite the Custom house, then to make report, and wait a regular permit for landing.

Martinot brought his goods to the Customhouse, where two city merchants, Francis Ayme and J.S. David, estimated the value to arrive at the duties payable. Martinot paid same to the collector, then faced a new hurdle. Although Dubourg gave permission for Martinot to take the goods to his friend and fellow agent Joseph L. Carpentier’s store in New Orleans, as they were repacking the trunks, naval officer Edwin Sequin abruptly stepped in and declared he would seize the goods, and did so.

Martinot immediately went to get Lynd to come to the Customhouse and speak to Seguin about the matter to demand the goods be delivered up to Martinot, to which Seguin probably blithely replied he would not do so then, but only after he had had the quantities and qualities of the goods verified, and their value estimated by two other merchants. This resulted in Martinot filing a protest on August 11 with Lynd against the naval officer and all others for any losses and damages suffered by the unwarrantable detention and seizure of the Melita’s goods. (He must have wondered at this point why he had even bothered to try to do the right thing in not smuggling the items into New Orleans.)

By the 10th of September, Martinot had settled the lengthy matter of dispersal of the goods and purchased the necessary items to repair the Melita, so he left New Orleans for Grande Terre, taking the speedy bayou route and arriving on Sept. 14. To his dismay, he found the schooner moored to the shore, half full of water, and was told by the officer left in charge of her that he had been obliged to run her on shore as he had been fearful she might sink otherwise. On the 15th, the Melita was pumped dry, and Martinot told the Baratarian carpenters to begin the repairs immediately in order to get the ship to New Orleans as soon as possible. He decided to store the ship’s sails, rigging and provisions in Laffite’s warehouse. Martinot probably breathed a sigh of relief, but then the hurricane of the US Navy descended early on the morrow.

Around 8 a.m. on Sept. 16, Patterson and Ross made the island of Grande Terre after a five day journey of the US Carolina, barges and gunboats down the Mississippi River. In a letter to the Secretary of the Navy William Jones, Patterson recounted that they discovered “a number of vessels in the harbor, some of which shewed Carthaginian colors.” Within an hour, the “pirates” formed a “line of battle near the entrance making every preparation to offer me battle,” so Patterson and Ross formed an order of battle themselves, then found the Carolina drew too much water to cross the bar and enter the harbor. The closest she could approach, wrote Patterson later, was two miles from the bar, as otherwise she would ground.

The Baratarians then made signals to each other with smoke along the coast, and Patterson said at the same time, “A white flag was hoisted onboard a schooner at the fore, an American flag at the main masthead, and a Carthagenian flag below.” As Patterson replied with a white flag, he saw that the Baratarians had set fire to two of their best schooners, so then he made the signal for battle, and the chase began, with the Baratarians dispersing rapidly without firing on the Americans, or offering any resistance, other than setting fire to their own ships. This unexpected response irritated Patterson greatly, as he was spoiling for a glorious battle, and later he stated in his letter to Jones , “I have no doubt the appearance of the Carolina in the squadron had great effect on the pirates.” As soon as he left Barataria, while he was at the Balize, Patterson dispatched a letter to Louisiana governor William C.C. Claiborne, crowing about his success, and boasting that “From the number of the enemy’s vessels, and their advantageous position, I had anticipated a sharp, short contest which must have terminated most fatally to them,” but instead of fighting, the Baratarians had scattered, which Col. Ross ignorantly attributed to their fear of seeing the American flag at the mast of the Carolina…even though the Carolina could barely get near enough to Barataria Pass so the privateers could see her colors.

In addition to the spoils of the raid, Patterson and Ross and their men brought six Baratarian ships to New Orleans, including three which Patterson boasted were “admirably adapted for the public service on this station, being uncommonly fleet sailors and light draught of water, and would be of infinite public utility.” (Those same ships would sit at the New Orleans wharf throughout the time of the British invasion, presumably caught up in legalities to prevent their use until properly adjuticated, even though Jackson’s martial law edict of Dec. 16 would have superceded any bars to their use by American forces. It has never been explained exactly why those ships sat idle, except for the fact that following the Barataria raid Patterson found it almost impossible to obtain any sailors.)

Martinot was only one of more than a few merchants and other visitors to Grande Terre who were accidentally caught up in the Patterson-Ross raid, but he seems to have suffered the most collateral damage from it. He had tried to do everything properly and by the book, only to learn that when greedy naval officers act like the pirates they claim they dispersed in their rush to seize money, ships and goods, the rule books get thrown overboard.

NOTE: Thanks go to Sally Reeves, archivist of the fabulous Notarial Archives of New Orleans, for providing the John Lynd notarial acts involving Joseph Martinot and the Melita. The Notarial Archives is a veritable treasure-trove of historical information, with literally thousands of such stories as Martinot’s waiting to be told.

Also See:

The British Visit To Laffite: A Study of Events 200 Years Later

Commemoration of a Hero: Jean Laffite and the Battle of New Orleans

The Case of the Spanish Prize Ship at Dauphin Island

Recent Comments