Laffite Talk at Battle of New Orleans Historical Symposium Jan. 10, 2015

October 5, 2014 in American History, History, Louisiana History, Native American History, Nautical History

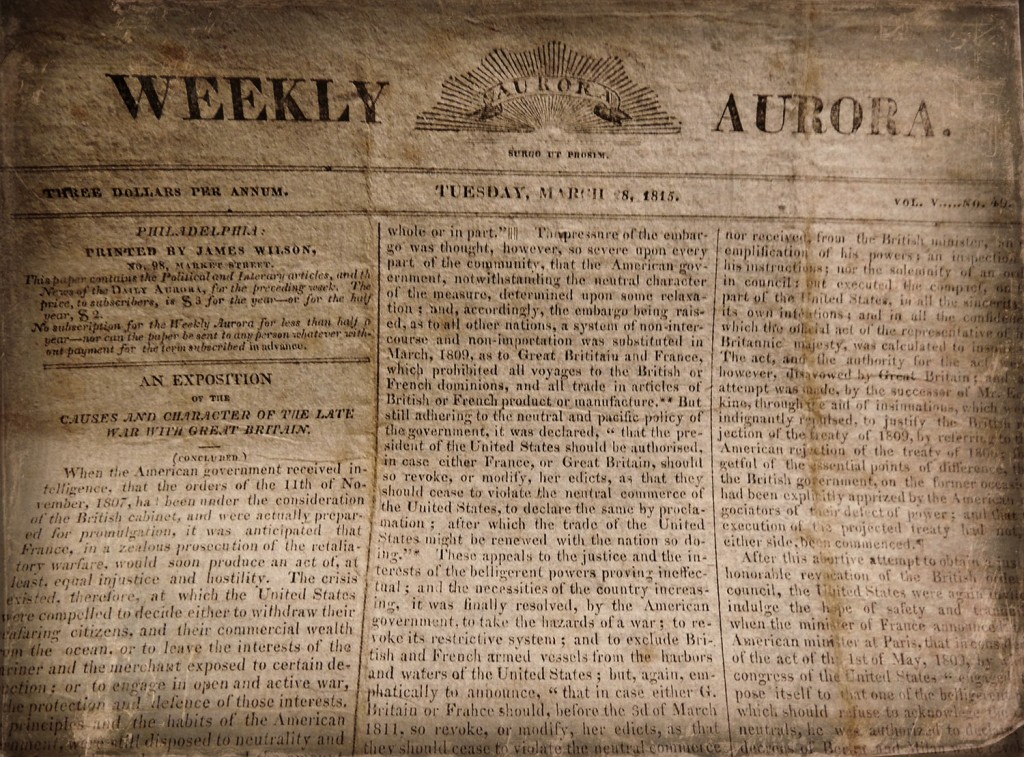

Get your travel plans ready now for the Third Annual Battle of New Orleans Historical Symposium slated Jan. 9 and 10, 2015, at Nunez Community College Auditorium at Chalmette, La., near the Jean Lafitte National Historical Park.

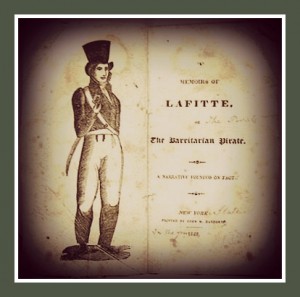

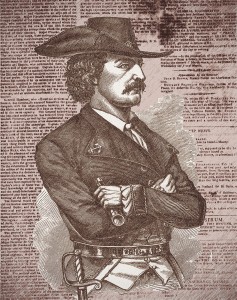

Among featured speakers will be William C. Davis, who will deliver the keynote address about “The Pirates Laffite” at 1:30 p.m. Jan. 10. Davis is the author of The Pirates Laffite, the Treacherous World of the Corsairs of the Gulf, largely regarded as the most definitive biography of the Laffite brothers ever written.

Director of programs for the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Tech before his retirement, Davis is a widely sought speaker who has written over 40 books on Civil War and other Southern US history.

Here is the full schedule for the symposium, which will be presented by The Louisiana Institute of Higher Education:

The Third Annual Battle of New Orleans Historical Symposium

January 9th & 10th, 2015 – at the Nunez Community College Auditorium

(You will hear lectures likely on the very spot that soldiers mustered for the Battle – though some comforts have been added in the last 200 years)

Friday, January 9th, 2015

A British Perspective

10:30 to 10:35 am – Welcome – Dr. Samantha Cavell

10:40 to 11:15 am – The Battle: January 8th, the Fateful Day

Ron Chapman will discuss the Battle, especially the operations on the West Bank.

11:20 to 12:05 pm – Jazz Brunch Demonstrations, exhibits/artifacts, informal interaction

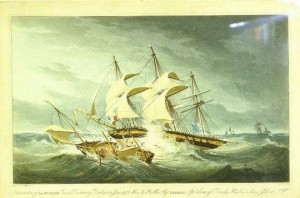

12:10 to 12:45 pm – Cochrane, Tonnant, and the War of 1812: A British Admiral and His French Ship in the American War

William Griffin will deliver a portrait of a dominant yet often dismissed figure in the War of 1812: the honourable Sir Alexander Forester Inglis Cochrane, Knight of the Bath, Vice Admiral of the Red Squadron of His Majesty’s Fleet, Commander in Chief of His Majesty’s Ships & Vessels on the Halifax & Jamaica Sations, as well as of his favourite ship, HMS Tonnant, 80 guns.

12:50 to 1:25 pm – The British Navy – Dr. Samantha Cavell

1:30 to 2:05 pm – What might have happened to America had the British won – Dr. Robert Wettemann, U.S. Air Force Academy Center for Oral History

2:10 to 2:45 pm – Andrew Jackson – Dr. Jason Wiese, Williams Research Center

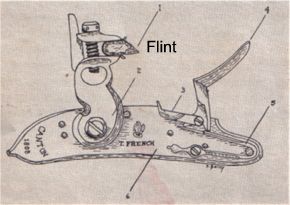

2:50 to 3:25 pm –Weaponry in the Battle-Philip Schreier, National Firearms Museum

3:30 to 4:05 p.m.-History of the 44th Regiment of Infantry from Activation to Consolidation 1812-1815)-Harold Youman

4:10 to 4:15 p.m.-Closing Remarks-Curtis Manning

All events, including the Jazz Brunches, are free and open to the public. At 3710 Paris Rd., Chalmette, LA. Parking is nearby and free. Contact Curtis Manning (504 512 5120 / manning.curtis@gmail.com) for details

Saturday, January 10th, 2015

An American Perspective

10:30 to 10:40 am – Welcome – Martin K. A. Morgan

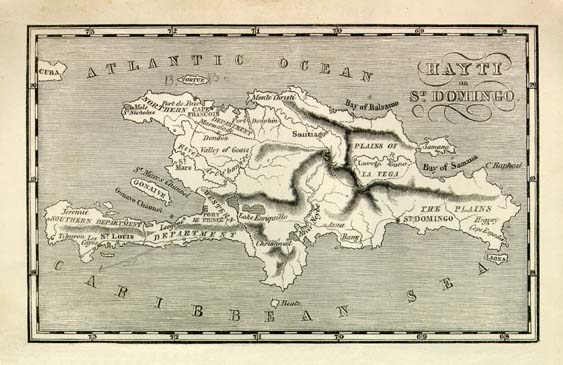

10:40 to 11:15 am – St. Bernard Parish in 1815 – Dr. Christina Vella

11:20 to 12:05 pm – Jazz Brunch Demonstrations, exhibits/artifacts, informal interaction, book-signings

12:10 to 12:45 pm– Locals & the land (Chalmette, Denis de La Ronde and Villere)-William Hyland

12:50 to 1:25 pm – Kentuckians – Eddie Price

1:30 to 2:30 pm –Keynote Address – Pirates Laffite – William Davis

2:35 to 3:10 pm – Free People of Color & Slaves – Dr. Ina Fandrich

3:15 to 3:50 pm – The Experience of Defeat: the Influence of the Battle on Post-War National Defense Planning

Martin K. A. Morgan will compare the construction of the U.S. 3rd System of Fortifications after the War of 1812 to the construction of the French Maginot Line after World War I and argue that, in both cases, the experience of defeat led swiftly to a frontier-oriented defensive posture that was both costly and ineffective

3:55 to 4:00 pm – Closing Remarks – Curtis Manning

Recent Comments