Was the Journal of Jean Laffite an Original, a Copy or a Forgery?

October 19, 2013 in American History, Ancient History, Caribbean History, general history, History, Louisiana History, Texas History

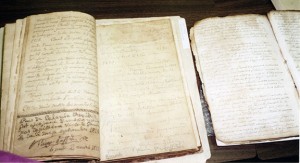

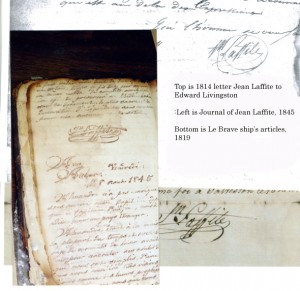

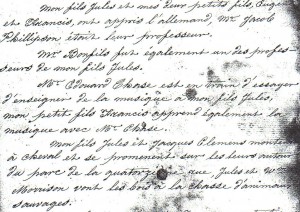

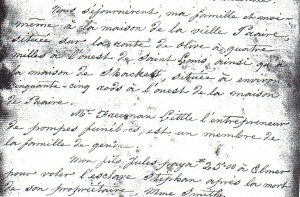

This photo of the Laffite family copybook on the left and the Journal of Jean Laffite n the right was contributed by Pam Keyes. Both documents were acquired by the Sam Houston Regional Library from John A. Laffite.

What is the difference between a forgery and a copy? How can you tell something is a good copy of an original document and has not been altered? And if it is, indeed, a copy, how do you go about recognizing alterations in the copied document? What is the distinction between a facsimile and just a copy, and is every good forgery a facsimile?

These are questions that come up over and over again in life. Sometimes people rely on physical evidence to determine the age of a document, based on the age of the papyrus it is written on or the ink it is written in. If it’s a clay tablet, carbon dating can help establish its age.

But the age of a copy is not conclusive when it comes to the question of when the original might have been written. Here is one example: we have many, many copies of the Old Testament. But we have no original. That does not mean that there was no original; it may have been written so long ago that it would have been destroyed by now, and the only reason we know about it is because of the copies. It is also possible that the original of some or all of the books was not written down but passed orally from one generation to the next, so that the scribe or scribes who first wrote it down were not the authors of the text. The original might have been a sequence of memorized words that passed from one living brain to the next until someone transcibed it. Once transcribed, this text was copied extensively. The copies were not forgeries. They were not meant to pass for originals. They were merely meant to transmit and preserve the text. Copies are all we have.

The copies were made by scribes, and their job was to write down word for word, letter by letter the same things as the scribe who came before them did. But sometimes a scribe made an error. Sometimes the error is so obvious that any modern reader of Hebrew could point it out and correct it, as if it were a typo. But because the scribes were sworn to copy exactly what was written and not add or subtract a jot, when they spotted an error, they just kept copying it word for word, letter for letter. Over the generations, quite a few errors accumulated.

In addition to all this, since the Old Testament is composed of more than one book, written at more than one time, by more than one author, there are arguments about which books are more authentic or which are just something that got inserted much later and really does not belong there. And also, some things have been intentionally altered by later scribes to go along with changing social mores and religion. Biblical scholars often have to use document-internal evidence to try to ferret out what is what. And the discovery of an older copy, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls or the Kaifeng Scrolls, which may have been less open to more modern tampering, can shed some light on what the original is more likely to have been like.

Having established that authorship and scribeship are separate issues, we should also take into account the difference between the copy of a document’s textual content and a facsimile copy which is meant to represent exactly how the original document looked, even though it is not the original.

In the case of the Old Testament, scholars now understand that when the text was first set down in writing, it could not have been in the Assyrian script in which Hebrew is currently written, which was borrowed from Aramaic and imported into use for Hebrew after the Babylonian exile. Instead, early Hebrew was written in letters more nearly resembling the ancient Phoenician alphabet. But as much as the letters were different in appearance, it was still the same alphabet with a one to one correspondence of symbols to symbols. Hence the text has come down to us letter by letter transcribed, though the letters look entirely different from those in the original. The text matters. What it looks like, considering that there is no original, does not matter. Nobody claims that any of the scrolls that we currently have access to, however ancient, is a facsimile copy of an original.

In all these cases, none of the copies are deemed to be forgeries, just because they are not original. Forgery, for the purposes of this discussion, would only occur if a modern person tried to create an older looking scroll and pass it off as something that it is not. But even in the event of such an attempt, most of the text would still be an accurate copy of another copy. The thing that would make it a forgery would be trying to pass a new copy off as an old copy. It would not change the document’s validity as some sort of copy of a very old document that no one currently living has ever seen the original of.

The Old Testament is not the only book to be subject to this kind of scrutiny or to require this type of analysis. Many a copied document can be found which has no original extant, and all can be subjected to the same type of analysis.

Take what is commonly known as “The Journal of Jean Laffite.” Ostensibly this was an original document presented by John A. Laffite, aka John Andrechyne Laflin, aka John Nafsiger or John Matejka, as the original, unaltered one and only journal of the famed privateer. Some have claimed it to be a forgery, created by the man who presented the document to the public. But even if it is a forgery, what exactly would that mean to those who are interested in the text rather than in the artifact in which the text is embedded?

The Journal as an artifact is a kind of notebook written upon by an ink pen, with a number of old newspaper clippings inserted within, and with some drawings and other extraneous matters. To determine its age would allow us to know if it was written at the same time as the text purports to have been written, but it does not tell us who is the author of the text, nor when the text was composed.

Composing a text and writing it down are two very different things. In some cultures, oral texts are passed on from one generation to another until one day someone writes them down. The person who transcribes these oral texts is not the author. That person is merely a scribe. Authentication of the text, in the event the scribe is suspected of having invented it, involves finding other versions of the same text elsewhere, circumstantial evidence of the existence of the text that long predates the writing and also text internal evidence that indicates through linguistic cues just how old the text really is.

In determining whether the Journal of Jean Laffite text is a hoax devised in the twentieth century or a genuine text from the period and by the person it is ascribed to, here are some of the issues that must be addressed:

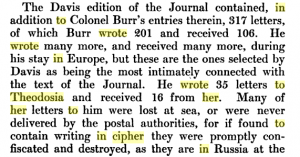

- The language in which it is written: in this case, a Creole French patois common to the Cuba-Haiti islands sprinkled with some hispanicisms. According to linguist Gene Marshall, who studied and translated it, the writing is in a style common before 1850.

- The spelling and other idiosyncracies not common to all writers of the dialect.

- The story it tells in terms of its detail and accuracy.

- Whether it is similar to other such documents, if any are available

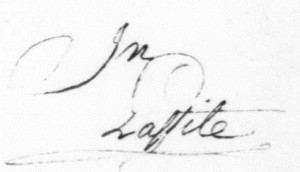

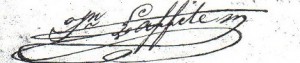

- The voice of the author or narrator, and whether it conforms to the voice of other available documents known or believed to be written by Jean Laffite in the latter part of his career.

- The handwriting, but not necessarily as proof of scribeship or authorship, but as possibly pointing to the author or the scribe of the original document, in the event that it is a forgery.

If the text is genuine, but the particular copy which we have available at the Sam Houston Regional Library and Research Center is not the original or not of concurrent age with the text, then it may well be a financial loss to the institution that purchased it, as its market value would be greatly reduced. But its value as a historical text would in no wise be diminished, if the sequence of words that it enshrines is a genuine and authentic transcription of a text whose author was the privateer Jean Laffite. That is the difference between the value of a forgery and the value of an accurate copy of a text.

It is said that John Andrechyne Laflin, aka John A. Laffite, aka John Nafsiger, did not speak French at all. It is said that those French speakers he had access to were not speakers of that dialect of French used in the Journal. It is known that there was not just one copy of the journal but at least two, as another copy was lent to Madeleine Fabiola Kent, who used it as background information when writing her novel The Corsair. If all these facts are true, and if indeed it were to turn out that John A. Laflin/Laffite/Nafsiger did copy the text of the Journal of Jean Laffite in a hand that looks very much like that of the famous privateer’s, then he could not have been its author, though he may have been a forger. If he was a forger, what did he forge? A copy of an original. But the very existence of the copy tends to corroborate the existence of an original.

How could a man who did not read or write French forge a document in a French Creole? One way is if he was indeed an expert artist, by looking at the original not as a text at all, but as a picture that must be copied line by line, angle by angle, correctly, much in the way a photocopier duplicates a text or a photo without understanding what it is copying. To do this, a forger has to be a great savant or a great artist. There is no evidence that John Andrechyne Laflin/Laffite/Nafsiger had that kind of skill or talent. Even if he did, the Journal of Jean Laffite is probably not a facsimile copy of the original journal, because it incorporates genuine newspaper clippings into the notebook in which the journal is copied.

Even if there was no forgery, and the document known as the Journal of Jean Laffite was actually written by the hand of Jean Laffite himself, it is still a copy. There is nothing blotted out. The text flows without interruption. Clearly this is a composed text whose composition took place elsewhere than in this notebook. The copy we have is just a copy. And there were other copies, for it was Jean Laffite’s stated intention to leave a copy for each of his grandchildren, of whom there were several.

When examining the Journal of Jean Laffite for purposes of proving its authenticity or lack of same, it is also good to keep in mind the following basic rules of thumb:

- Though Jean Laffite may be the author, this does not mean that everything he wrote was true – or for that matter, that anything he wrote was true. People have been known to prevaricate when telling the story of their lives. They have even been known to misremember. Therefore, finding an inaccuracy or historical untruth does not necessarily cast doubt on the authenticity of the text.

- If the language of the text is very different in one or more sections than in the body of the work, it is more likely that those parts are not part of the original document but were added or embellished upon later.

- Suspected alterations should be judged by the four corners rule for document interpretation: the internal consistency of the document will determine what parts must be errors or extraneous.

A forgery is an attempt to create a facsimile copy that passes for an original. A forged signature, for instance, to be effective, needs to duplicate an original signature almost identically. A copy that is not a forgery is merely the transmission of a text through duplication. It need not look the same in its typography or handwriting. Sometimes a copy is also a forgery. But being a forgery does not necessarily prove that a copy is a bad copy. In fact, the better the forgery, the more a copy resembles the original.

REFERENCES

http://www.historiaobscura.com/an-interview-with-pam-keyes-about-jean-laffite/ (For background on Jean Laffite scholarship.)

http://www.bubblews.com/news/1356968-what-is-forgery-and-why-is-it-wrong (About Forgery and the artistry it involves)

http://www.amazon.com/The-Memoirs-Jean-Laffite/dp/0738812536 (Gene Marshall Translation and commentary)

http://www.livescience.com/8008-bible-possibly-written-centuries-earlier-text-suggests.html (For what the Hebrew letters used to look like during the period when the Hebrew Bible was first written down.)

Recent Comments