The mosquito, a deadly foe to mankind.

Despite modern advances in medicine, there is a plague (one of many) that still haunts mankind around the globe and that is malaria. Malaria is a parasite spread by the female mosquito that affects your blood cells. Somewhere in the world, every thirty-five seconds, a child unnecessarily dies from this horrible disease. Of course today, we know that it is spread by the lowly female mosquito — who despite modern technology, modern medicine, and awareness has managed to outwit the humans who live within its many kingdoms. To understand the way that malaria and the mosquito have changed history, a trip down memory lane to Colonial America will yield a good bit of understanding.

Beginning with the first Europeans setting foot in the Americas, the would-be colonists and explorers, quickly became profoundly aware of their own mortality in the face of such diseases as yellow fever, smallpox, and malaria. Thanks to a compatible climate, those living in more Southern and temperate locations, such as Georgia, Louisiana, and the Carolinas would soon face an overwhelming reality exemplified by this quote:

“They who want to die quickly, go to Carolina.”

Along with people in the Louisiana and Georgia, during in the late 18th and 19th centuries in South Carolina, especially around Charleston, had such a high mortality that less than 20% reached their 20th birthday. Most of those who died did so because of malaria, or because of being in a weakened state after a bout of malaria. It’s almost unimaginable that so many mothers and fathers would be burying their children so young. Anyone who has experienced such a loss knows that this life event alters your life forever.

Another staggering set of statistics, just in the fifty years that one group, England’s Society for the Propagation of Gospel in Foreign Parts, was sending young men to South Carolina – of the total fifty young men (one per year), only 43% survived, and many resigned within five years of setting foot on South Carolina soil due to poor health from malaria. And, of course, it goes almost without saying the medical lack of knowledge as to what caused malaria back then, and how to treat it also was another gravestone upon many. It left much of the South a place to die rather than a place to live. Perhaps, no greater community suffered from the spread of malaria than those in and around South Carolina for more than a century (except those living in The Floridas and coastal Louisiana).

“More die of the practitioner than of the natural course of the disease.” – Dr. William Douglass

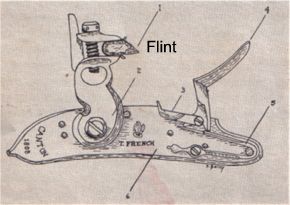

In Colonial days, the cause of malaria was unknown, and when people don’t know something they are scared of — they make up theories and stories as to why their loved one has departed from them. Different groups of people had different names for malaria. It was called ague; bilious fever, country fever, intermittent fever, remittent fever, tertian fever, and mal aira. Colonists believed that the fever, by whatever name, was caused by the methane gasses that could be seen arising from any nearby swamp, often referred to as “vapors” or miasmas” arising from the putrefaction in vegetation in the swamps from rotting plants and dead animals. People literally believed it came from bad air that attacked you somehow mysteriously in your sleep. Many of the folk tales of African slaves and the Acadians in Louisiana, had central themes tying folk monsters of the swamps such as the feux-folet of Cajun folklore being somehow connected to this disease.

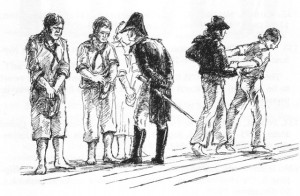

Additionally, deaths in Colonial America continued well into the early 1900s — when colonies became states, yet quackery, medical ignorance, poor hygiene, barbaric medical remedies such as blistering, phlebotomy, and purging all continually played a huge role in the malaria disease cycle. However, there was an obscure fact that is often ignored when it comes to malaria — and that is the role of the crops that early colonists and rural America chose to grow and how it contributed to the problem. In other words agriculture, plus temperate climate, plus natural terrain, all played a huge role in the spread of malaria. The female mosquito may have carried the disease, but we unwittingly invited her as a house guest when our early settlers decided to grow rice and indigo.

This was particularly true in the coastal regions of the Carolinas, Georgia and Louisiana, where the spread of malaria was quickened because rice and indigo cultivation. In order for both crops widely grown for commercial value, the necessary irrigation and pools of stagnant shallow water were important in making such places is a virtual mosquito growing nursery. Furthermore, the African slaves who worked the fields became the most likely first victims of malaria bearing mosquitoes. In turn, a mosquito biting a person with the malaria parasite spread the disease to rich and poor. The blood thirsty mosquito does not discriminate.

There are countless examples in history of this, one such Carolina example is that of a ten-year-old boy, the only son his parents would ever have. His father was the governor of South Carolina, his mother the daughter of a former U.S. Vice President, and yet no amount of money could protect him from malaria. Aaron Burr Alston, died from a mosquito bite, despite having a family rich enough to sleep under a “Pavilion of Catgut Gauze” the choice of the rich in terms of what we call mosquito nets today. Like countless others of unfortunate victims to malaria, the world will never know what this one little boy or his descendants could have accomplished — a common bond between every malaria victim.

The grave of Aaron Burr Alston who was another loss to history by malaria. His father, Joseph Alston was buried in the same grave.

Breeding sites for the female Anopheles mosquito were also naturally prolific between great thunder storms and annual hurricanes. Drainage especially around both agriculture and towns were another contributor to the huge problem. It was reported that mosquitoes were so thick that they could blacken an arm in sheer numbers at times and were documented in the deaths of killing cattle by suffocation of the nostrils. While malaria by itself, actually doesn’t kill the vast number of people who succumbed to it, malaria does weaken its victim’s resistance to other diseases they wouldn’t have normally been bothered by. Side effects after having had malaria are: anemia, fatigue, proneness to infections, pneumonia and a greatly weakened immune system. Once over the initial bout of malaria, victims were also likely to have reoccurring attacks of malaria and never really recover completely.

Malaria also preys on the defenseless, infants, small children, and the elderly were all groups that had high mortality rates. Women often contracted malaria during pregnancy were also prone to miscarriages, premature labor, and death. It was the leading cause of death for Colonial Southern women. More people would die in the Americas from it than all of the deaths from wars fought within our borders, especially during the War of 1812 and the Civil War.

Soon, it would become apparent that cinchona bark, similar to quinine was an effective cure, but the people of that those days still lacked the ability to understand the true cause and carrier of the disease. Others favored alternative remedies and ineffective healing attempts, such as St. John’s Wort, mustard plasters, wormwood, and foxglove. Prevention methods of the day were the burning tobacco to clean the air, mud baths, blood letting, and mercury pills – all equally ineffective at best. Even netting around beds for the lucky who had them was not connected in the minds of people to stopping malaria – only a way of keeping biting and itchy insects off them while they slept.

Fast forward to today, where malaria is still a plague but not longer a mystery, except to the puzzle as to why mankind has not eradicated the disease now that we know the cause. How many more people will die from the bite of a mosquito? Will history continue to be altered because of malaria? This one quote says it all:

There are more people dying of malaria than any specific cancer.” — Bill Gates

Recent Comments