New Orleans merchants, planters, and other citizens rushed the Planter’s Bank, Bank of Orleans and Louisiana Bank in panic in mid April 1814, desperate to exchange their paper bank notes for specie (mostly gold and silver Spanish coins), but nearly all were refused, with the banks locking their doors early to avoid the hostile crowds. There was no specie to be had. Pandemonium ensued_ were the bank notes worthless tender?

The Louisiana public already was edgy due to the continuing wartime embargo and to the British warship blockade of the Balize below New Orleans. The British ships successfully harassed shipping by most merchants heading to and from New Orleans, plus the trade traffic from the Gulf of Mexico to the upper Mississippi River.. Almost the only ones who could avoid the blockades consistently were the Laffite brothers’ Baratarian privateers. The smugglers brought captured prize goods in to sell at auction, often at the Temple site near New Orleans, attracting large crowds of eager buyers who were only too happy to pay in silver reales, pieces of eight, and gold doubloons for such items as German linen, exotic spices, glassware, wine and other trade goods. Thanks to the restrictions of the War of 1812, the Laffites’ smuggling operation had a virtual monopoly on imported goods which were cheap due to avoiding the customs duty and the fact that the Laffites got them for free from captured Spanish prize ships.

When the New Orleans banks ran out of specie, it was only natural for the public to immediately pin the blame on the smigglers, sure that they, and they alone, had drained the port city of all that gold and silver.

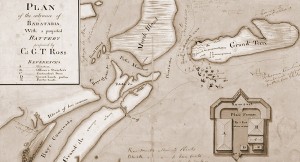

Stoking the fires of public animosity toward the Baratarians that spring of 1814 was none other than prominent New Orleans attorney Edward Livingston. At an address to a meeting of concerned citizenry at Tremoulett’s Coffee House on April 29, 1814, Livingston concurred with the generally held sentiment, accepted as fact by the populace, that the scarcity of specie could “be almost entirely ascribed to the encouragement shown to the Baratarian pirates.” When specie could be obtained earlier, “immense sums were daily carried away to purchase goods at Napoleonville, as Lafitte (sic) has not unaptly denominated the capital of his empire.” Many planters made trips to the Laffite base at Grande Terre to purchase slaves and other goods, and it was Grande Terre that was nicknamed “Napoleonville.”

It is particularly curious that Livingston agreed with the public at this meeting that the Laffites were to blame, since at almost the same time as the bank run, Livingston was named chairman of the secretive New Orleans Association, an expansionist group of the elite which had evolved from the previous Baratarian Association of the Laffites and their privateers. The Laffites were members of the New Orleans Association, so apparently Livingston was playing both sides against the middle. Interestingly, it was also during this time period that Livingston became the power broker for the some 21 members of the elite who controlled the ciy economically and politically.

Presidents of all three New Orleans banks agreed it was in the best interests of the community to suspend payments in specie and to accept each other’s bank notes as payment in kind. They assured their customers that nothing would be neglected “to preserve your properties their full value, and maintain the public credit at a moment when the want of specie may produce the ruin of various classes of the community.” The statement was published widely and signed by Thomas Urquhart, president of the Louisiana Bank; Dusuau De La Croix, for the president of the Planter’s Bank, and Benjamin Morgan, president of the Bank of Orleans.

A committee composed of merchants William Nott, Caizergnes, H. Landreaux and P.F. Dubourg and attorney Mazureau was formed to investigate the cause of the shock upon the public credit in New Orleans, a shock which contemporary newspapers said was “severely felt through all the ramifications of Society.” According to New Orleans merchant Vincent Nolte, this committee did find the true cause of the specie shortage to have been a personal vendetta between the two chief cashiers at the Planter’s Bank and Bank of Orleans, T. L. Harman and Joseph Saul (both British-born immigrants), but the committee chose not to inform the public of this fact. Instead, the specie shortage was blamed on the “accumulation of produce in our stores, for which there is no vent, and in the difficulty, not to say the impossibility, of receiving supplies through the usual channels.” In other words, they blamed the wartime embargo. The public dismissed this finding outright and continued to blame the Laffites and their men.

The species shortage continued throughout the summer with no relief, and animosity toward the Laffites simmered among the very merchants who had profited handsomely from their smuggled goods in happier times. Even some of the privateers’ French friends were getting hostile.

By early July 1814 things reached a boiling point and Pierre Laffite was arrested in the French Quarter on a charge of piracy and thrown into the Cabildo jail. A grand jury formed around the same time, and issued indictments for piracy among other Baratarians as well. Jean Laffite stayed around Grande Terre and avoided the authorities. He wrote a letter to the editor of the Louisiana Gazette and New Orleans Advertiser in which he tried to allay the public’s suspicions about the earlier specie disappearance from the banks. Jean wrote that several rich prizes had been brought into Barataria, and that the public could share in the profits of the trade, as specie was not the only payment accepted. He stressed bank note money of the banks of New Orleans also would be received for goods sold, pointedly saying this was proof of the “blind and stupid opinion of the late Grand Jury of this city, who stated that our trade contributed to drain the country of its specie.” He stressed, “We deal in specie instead of carrying it away.”

However, the die was cast in the public eye of not only the New Orleans area, but throughout the nation, as reports of the Baratarians’ actions draining specie made the newspapers throughout the country. The negative public relations would soon prove disastrous to the Laffites and their operations.

When the British ship Sophie and Captain Nicholas Lockyer visited Grande Terre the first week of September 1814 and tried to bribe Jean Laffite into siding with the British, Jean wasted no time in turning over the British letters to Louisiana Governor W.C.C. Claiborne via Jean Blanque, saying he wished to assist the American cause. This was the chance at redemption that the Laffites needed, but it was far too late. Pierre Laffite escaped from the Cabildo jail even as the governor and his council perused the letters, and naval Commander D.T. Patterson already had orders in place to blast Barataria to bits, confiscate ships and property there, and arrest whomever could be caught. The public was not made aware that the Laffites had offered to help in defence. The existence of the British letters was later made public, but it seems everyone thought those were among the papers found by Patterson during his raid on Barataria.

Patterson and his gunboats arrived at Grande Terre on Sept. 16 and met with no resistance from the privateers present, per Jean’s orders not to fire on Americans. Both Jean and Pierre Laffite escaped to friends along the the German coast above New Orleans. Second in charge Dominique Youx and several other Baratarians were taken prisoner and placed in jail in New Orleans to face possible hanging.

In late September, a ship finally arrived in New Orleans from Vera Cruz with much-needed specie on board. The specie was immediately deposited in the Planter’s Bank but was not exchanged for bank notes among the populace.

The Laffites were now fully aware of how dire their situation was. In early October, 1814, Jean Laffite wrote a letter of entreaty to Livingston, thanking him for earlier assistance and begging him for whatever help he could provide in rescuing him from his current troubles. Livingston, for his part, was telling the newly formed Committee for Public Safety of which he was chairman, that the Baratarians’ assistance could be helpful for the American cause. Meanwhile, the Grand Jury was continuing to hand down indictments to not only Baratarians, but also to some New Orleans merchants whose papers had been found in the raid on Grande Terre,

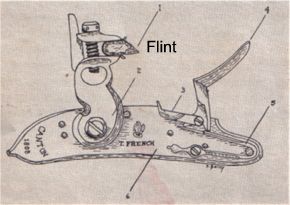

When Major General Andrew Jackson arrived at New Orleans in early December, Edward Livingston was probably the one who convinced him to accept the Baratarians’ assistance in defending the city from the British. By mid December, Dominique and the other jailed privateers were freed on a conditional pardon, and the Laffite brothers emerged from hiding. Jackson’s men were poorly armed and had no backup supplies. Jean Laffite and his men provided all the gun flints and powder that the Americans had through the ending battle of Jan. 8, 1815, according to Jackson’s later accounts. Jackson also praised the Laffites and their men for their assistance in winning the battle against the British.

In reflecting about how all this came about, and the available information about the political and economic condition of the city, it seems the Laffites were motivated to help the Americans to expunge the extremely negative aftermath of the bank run of April 1814. The damage to their social standing was already done, though, and could never be wiped clean.

One has to wonder what would have happened if, at the time of the bank run, the public had been made aware that the real reason for it was that cashier Joseph Saul of the Bank of Orleans wanted to attract the Planter’s Bank customers of cashier T.L. Harman to his own bank as they were mostly planters who allowed their deposits to lie longer than the merchants were accustomed to do. Saul had collected his rival’s bank notes until he had amassed a large group, then presented it to the Planter’s Bank on a day when he knew the amount of the notes far exceeded the silver held by that bank, Then Saul made sure everyone at the coffee house knew about the shortfall, and the run on the Planter’s Bank happened, but it didn’t end there. The public also rushed to the other two banks, demanding specie when there wasn’t specie to be had. So why didn’t the investigating committee tell the public the true reason for the bank run? Most likely, no one wanted to be called out to a duel by Saul, who was notorious for being a hothead and an expert boxer who thought nothing of beating someone up for irritating him.

People will always believe what they want to believe, so even if the truth of the matter had been stated at the time, perhaps the Baratarians would still have been blamed. Perhaps not.

Maybe, in a what if alternate ending, the Patterson raid would never have happened, and the Laffites would have moved away from New Orleans before the British invasion so they couldn’t have been said to have assisted the British; Jackson and his men would have had no flints or powder to fight the British when they advanced at Chalmette on that famous day of Jan. 8, 1815 and thus would have lost the battle. General Pakenham would have lived and declared a British victory. The Treaty at Ghent would be nullified, the US would have returned to British rule. Everything would have turned out differently, all due to a case of petty jealousy among two bank cashiers.

Recent Comments