The Aurora Editor Snipes at Britain, Post War of 1812

September 30, 2014 in American History, European History, general history, History, Louisiana History

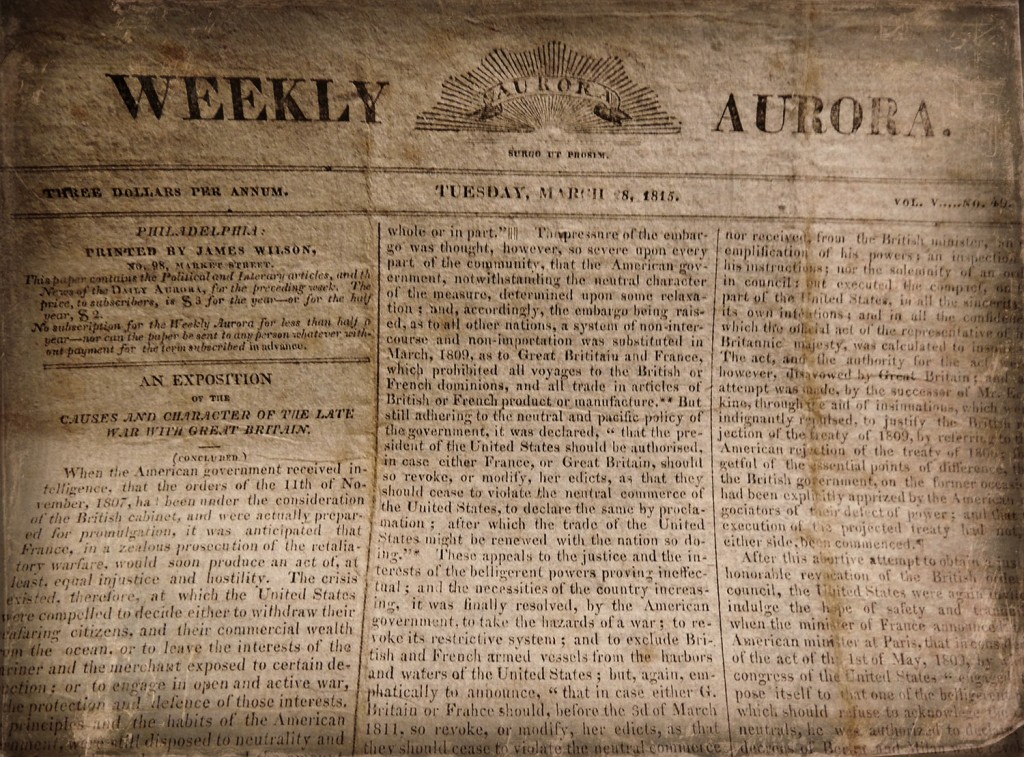

With one of those quill pens he so often had wielded to acidulously attack targets in his Weekly Aurora newspaper at Philadelphia, Editor William Duane reflected at length in March 1815 about the Causes and Character of the Late War with Great Britain, in an exposition that flowed like a river of tiny type and took up three weeks’ worth of issues of his Jeffersonian Democrat newspaper, a publication which was widely read by both his admirers and his Federalist and British detractors. Duane included the British visit and offer to Jean Laffite in a portion of this work, published March 28, 1815:

“Great Britain has violated the laws of humanity and honor, by seeking alliances, in the prosecution of war, with savages, pirates, and slaves.

…when the war was declared, the alliance of the British government with the Indians, was avowed, upon principles, the most novel, producing consequences the most dreadful_The savages were brought into the war, upon the ordinary footing of allies, without regard to the inhuman character of their warfare, which neither spares age nor sex, and which is more desperate towards the captive, at the stake, than even towards the combatant, in the field. It seemed to be a stipulation of the compact between the allies, that the British might imitate, but should not control the ferocity of the savages__While the British troops behold, without compunction, the tomahawk and the scalping knife, brandished against prisoners, old men and children, and even against pregnant women, and while they exultingly accept the bloody scalps of the slaughtered Americans; the Indian exploits in battle, are recounted and applauded by the British general orders. Rank and station are assigned to them, in the military movements of the Brtitish army, and the unhallowed league was ratified with appropriate emblems, by intertwining an American scalp with the decorations of the mace.

…the savage, who had never known the restraints of civilized life. and the pirate, who had broken the bonds of society, were alike the subjects of British conciliation and alliance, for the purposes of an unparalleled warfare. A horde of pirates and outlaws had formed a confederacy and establishment on the island of Barrataria, near the mouth of the river Mississippi. Will Europe believe, that the commander of the British forces, addressed the leader of the confederacy [Jean Laffite], from the neutral territory of Pensacola, “calling upon him, with his brave followers, to enter into the service of Great Britain, in which he should have the rank of captain; promising that lands should be given to them all, in proportion to their respective ranks, on a peace taking place; assuring them, that their property should be guaranteed, and their persons protected; and asking, in return, that they would cease all hostilities against Spain, or the allies of Great Britain, and place their ships and vessels, under the British commanding officer on the station, until the commander in chief’s pleasure should be known, with a guarantee of their fair value at all events?” There wanted only to exemplify the debasement of such an act, the occurrence, that the pirate should spurn the proffered alliance; and accordingily, Lafitte’s answer was indignantly given, by a delivery of the letter, containing the British proposition, to the American governor of Louisiana.

There were other sources, however, of support, which Great Britain was prompted by her vengeance to employ, in opposition to the plainest dictates of her own colonial policy. The events, which have extirpated, or dispersed, the white population of St. Domingo, are in the recollection of all men.Although British humanity might not shrink, from the infliction of similar calamities upon the southern states of America, the danger of that course, either as an incitement to a revolt, of the slaves in the British islands, or as a cause of retaliation, on the part of the United States, ought to have admonished her upon its adoption. Yet, in a formal proclamation issued by the commander in chief of his Brittanic majesty’s squadrons, upon the American station, the slaves of the American planters were invited to join the British standard, in a covert phraseology, that afforded but a slight veil for the real design. Thus, admiral Cochrane, reciting “that it had been represented to him, that many persons now resident in the United States, had expressed a desire to withdraw therefrom, with a view of entering into his majesty’s service, or of being received as free settlers into some of his majesty’s colonies,” proclaimed, that “all those who might be disposed to emigrate from the United States, would, with their families, be received on board his majesty’s ships or vessels of war, or at the military posts that might be established upon, or near, the coast of the United States, when they would have their choice of entering into his majesty’s sea or land forces, or of being sent as free settlers to the British possessions in North America, or the West Indies, where they would meet all due encouragement.” But even the negroes seem, in contempt, or disgust, to have resisted the solicitation: no rebellion, or massacre, ensued; and the allegation, often repeated, that in relation to those who were seduced, or forced, from the service of their masters, instances have occurred of some being afterwards transported to the British West India Islands, and there sold into slavery, for the benefit of the captors, remains without contradiction. So complicated an act of injustice, would demand the reprobation of mankind. And let the British government, which professes a just abhorrence of the African slave trade; which endeavors to impose, in that respect, restraints upon the domestic policy of France, Spain and Portugal, answer, if it can, the solemn charge, against their faith and their humanity.”

Duane took Great Britain to task for allying themselves with the “savage” Indians and their known depradations, then in having the lowness in character to try to associate with people some regarded as pirates, and, worst of all, trying to start a violent slave insurrection by promising the slaves their freedom for their help. For once, his exposition found friendly readers among most of the general public of the United States. Much of the lengthy opus was reprinted widely. The British, including his old arch-enemy journalist with a similar poison pen, William Cobbett, stayed silent on the matter. (By the spring of 1815, Duane and Cobbett had reconciled and become friends after a bitter battle in print that had lasted for over 15 years).

The Aurora, once a powerful publication that could help sway presidential elections (Jefferson claimed it helped him gain office), had declined in its political pull by the time the War of 1812 ended. By late 1815, Duane published a letter to the editor from the same “pirate” he had disparaged in his exposition earlier that year: the mercurial newspaperman’s favor was as capricious as the wind.

TO COME:

William Duane and “Peter Porcupine,” the Epic Battle of the Word-Dueling Journalists

Recent Comments