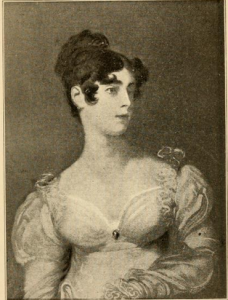

She was the daughter of the famous theologian, Jonathan Edwards, and the wife of the second President of Princeton University, but Esther Edwards Burr is best known today as the mother of Aaron Burr, Jr., the third Vice President of the United States. What did she have to say about her famous son? The only significant words she writes about him are these:

She was the daughter of the famous theologian, Jonathan Edwards, and the wife of the second President of Princeton University, but Esther Edwards Burr is best known today as the mother of Aaron Burr, Jr., the third Vice President of the United States. What did she have to say about her famous son? The only significant words she writes about him are these:

Aaron is a little, dirty, noisy boy, very different from Sally almost in everything. He begins to talk a little, is very sly, mischievous and has more sprightliness than Sally. I must say he is handsomer, though not so good tempered. He is very resolute and requires a good governor to bring him to terms.

That she had little more than this to say about her son results from the fact that Esther Edwards Burr died when Aaron was only two years old. That we know she said this much is because she kept a journal since she was nine.

Northampton, February 13, 1741.

This is my ninth birthday and Mrs. Edwards, my mother. has made me stitch these sundry sheets of paper into a book to make me a journal. Methinks, almost all this family keep journals: though they seldom show them. But Mrs. Edwards is to see mine, because she needs to know whether I improve in composing; also whether I am learning to keep my heart with all diligence, which we are all constrained to be engaged.

Born into a busy household of a famous evangelical preacher, Esther Edwards was given quite an education at home. Both her parents were as interested in her writing ability as they were in the purity of her soul. The journal she kept was subject to parental scrutiny, so we can be sure that she exercised self control and did not express all her thoughts and feelings. Still, considering all this, her personality does come through in her writing.

Northampton, December, 1741.

Mr. Samuel Hopkins, who has just been graduated from New Haven College, and who pleads to study divinity with Mr. Edwards, came to our house to-day. He looked to find father at home and is in some trouble of mind. …We girls, Jerusha, Mary and I, seeing his immense frame, his great honest face, and hearing his ponderous voice, have maliciously nicknamed him “Old Sincerity.”

Esther wrote about ordinary things that happened around her, but she also sometimes expressed original thoughts about serious topics in passing. Notice how the following passage starts with an ordinary domestic scene, but ends up making a commentary on slavery.

Northampton, June, 1743.

My mother has just come into the house with a bunch of sweet peas, and put them on the stand where my honored father is shaving, though his beard is very slight. We have abundance of flowers and a vegetable garden, which is early and thrifty. Our sweet corn is the first in town, and so are our green peas. My honored father of course has not time to give attention to the garden, and so Mrs. Edwards looks after everything there. Almost before the snow has left the hills, she has it plowed and spaded by Rose’s husband, who does all the hard work there. She is our colored cook. We hire her services from one of the prominent people in father’s parish, who owns both her and her husband. That word “own” sounds strangely about people.

Although the Edwards children were encouraged to read the Bible and engage in piety at all times, they were not kept in the dark about all forms of contemporary, non-religious culture. For instance, they were allowed to read novels, if their parents approved of their content.

Northampton.

We have just been permitted to read Richardson’s novel: “Sir Charles Grandison”. Our father and mother have first read it, and regard it as a wholly suitable book as to morals and character. Our honored father has gone so far as to express admiration for its literary style…

Jonathan Edwards was a strict father, and there were no parties till midnight for his children. But not everyone in town felt the same, and despite the dutiful adherence to the parental edicts, one senses a wistfulness when Esther reports on festivities that she was neither invited to attend, nor would have been allowed to go to in the event of an invitation.

Northampton, January.

Great excitement has been occasioned by a New Year’s sleigh-ride and ball for dancing, that has just occurred here. It was a gay party for young people, some of my more intimate friends among them, who drove to a hotel in Hadley and spent the hours till midnight in dancing the Old Year out and the New Year in. …To my honored father and mother it was a time of great grief. And when with morning light, the great sled-loads drove up through the streets, with their laughing, giddy freight, I saw the tears in the eyes of them both. I am only too glad that none of the children of this household were invited to go; or had they been, would have so far departed from the wishes of their parents…

You might think that with such impediments to socializing with the opposite sex as the Edwards household put up, Esther would have had to wait a long time before a beau materialized. Not so. She was just seventeen when she received her first and only marriage proposal.

Stockbridge, May, 1752.

This has just happened to me: Mr. Burr, President of New Jersey College, who has visited our house, both in Northampton and Stockbridge for many years — as a little girl I have romped with him and sat on his lap — rose this A. M. to take an early breakfast and start for home again, betimes on horseback for the Hudson. And it was my week to care for the table. I had spread the breakfast for him, no other member of the household having yet arisen. The cloth was as white as snow, for I had taken out a fresh one with its clean smell for the occasion, and there was not a crease in it; the room was full of the aroma of freshly made tea… The newly churned butter was as yellow as gold… Mr. Burr partook with the greatest relish, keeping up a current of gracious speech every moment; and finally fixing his flashing eyes on me, as I sat rapt and listening at the other end of the board, he abruptly said: “Esther Edwards, last night I made bold to ask your honored father, if I can gain your consent, that I might take you as Mrs. Burr to my Newark bachelor quarters and help convert them into a Christian home. What say you?” Of course, although from my early girlhood, Mr Burr had treated me with favor, I was wholly unprepared for this sudden speech, and blushed to my ears and looked down; and stammered out, as we are taught to say here: “If it please the Lord!” Though when we came to separate, I could not help playfully saying: “Was it the loaves and fishes, Mr. Burr?” He laughed and kissed me for the first time.

Today, we tend to think of women being less educated in times past, but when we read the journal of Esther Edwards Burr and compare her education with that of the average young woman of today, she comes off as rather a learned scholar. We are taught that one of the reasons young women should wait to marry later is so that they can complete their education. Even though she married young, Esther Burr’s education did not end upon her marriage. In fact, her husband saw to it that she learned things she might never have been taught in her father’s house.

Newark 1752

My husband, Mr. Burr, has persuaded me to take up Latin with him. I had learned it a little in our home in Northhampton, where there was much teaching of the classics. And last evening he read with me a letter of the Roman orator, Cicero. addressed in his exile ‘To his dear Terentia, his little Tullia and his darling Cicero.’ Mr. Burr believes it to be genuine. Mr. Burr was speaking of Cicero’s surprise that great calamity should have overtaken one, whose wife had so faithfully worshiped the gods, and who had himself been so serviceable to man…

Cicero was not the only orator quoted in the Burr household. nor were political events closer to home ignored.

Newark, January 1, 1755.

“A day set apart for fasting and prayer, on account of the late encroachment of the French and their designs against the British Colonies of America.” President Burr preached what was largely a historical discourse, giving the French progress from the time of Henry the IV. These were the closing paragraphs: “Shall we tamely suffer our delightful possessions to be taken from us? Become the dupes and slaves of a French tyrant? God forbid! Tis high time to awake, to call upon all the Briton within us, every spark of English valor, cheerfully to offer up our purses, our arms, and our lives to the defence of our country, our holy religion, our excellent constitution and invaluable liberties. For what is Life without Liberty? Tis not worth having….”

Reading this today, one is reminded of the wording “our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor.” The historical influences that contributed to the making of the American Revolution run deep, and in reading Esther Edwards, we realize that the British colonists were well rooted in a long, long tradition of honor and love of liberty. Modern day Americans, in comparison, are historically rootless, able to quote very few of their predecessors.

In time Esther Burr gave birth to a daughter and then a son. But she was not to have the privilege of raising her children, for she succumbed to the small pox when she was only twenty-three, following the death of her husband, leaving behind two little orphans. Although the life she led was short, Esther Edwards Burr packed a lot of living into those years and she left her mark on the literary history of Colonial America by means of her own writing.

Recent Comments