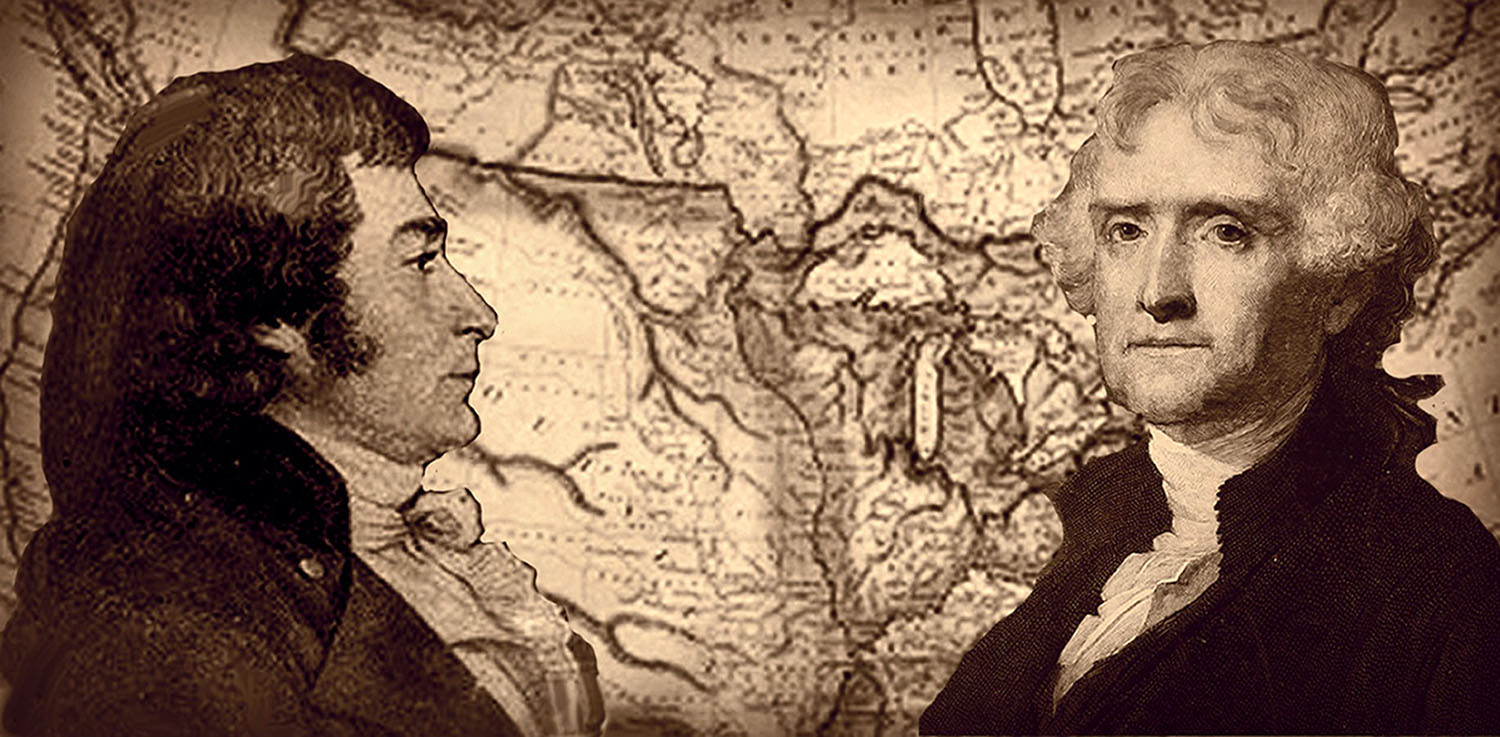

One Vote Made Thomas Jefferson President

May 18, 2016 in American History, general history, History, Legal History, Louisiana History

Astonishingly, only one vote from a very young Tennessee state representative handed Thomas Jefferson the presidency of the United States in the 1800 Election.

The 25-year-old who cast that ballot was William C. C. Claiborne, who as a direct result of his vote that spring of 1801 was appointed governor of the Territory of Mississippi a few months later by a grateful Jefferson. The Federalist governor in place, Winthrop Sargent, had faced heavy criticism for his authoritarian rule of the territory, and the residents there did not mourn his removal from office although Sargent bitterly complained in the press.

In the Presidential Election of 1800, the US Constitution had not required that electors should designate on their ballots the person they voted for as president, and the one voted for as vice president, but that the one having the highest number of votes should be president, and the one having the next highest should be vice president. This made the end vote of the Electoral College confusing, although the popular vote had given the Jefferson-Burr ticket a majority.

Incumbent President John Adams had lost the popular vote dramatically to candidates Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, which threw the final decision into the Electoral College. But the Electoral College gave Jefferson and Burr an equal number of votes, so the House of Representatives had to decide which of them should be president, the choice to be made by ballot, and each state would have but one vote.

According to a historian writing in 1830, “the contest was extremely animated, for on this occasion the great federal and republican parties came into violent conflict…when they were returned with an equal number of votes to the house of representatives, it was supposed of course that the public voice would be obeyed, and Jefferson made president. The federal party, however, determined to support Colonel Burr; they knew very well the political sentiments of every member of the house of representatives, and they early ascertained that the election depended on the vote of Mr. Claiborne, the sole representative from the state of Tennessee.”

Claiborne was thought to be especially vulnerable to being influenced as he was young with grand ambitions, plus the most important factor was he was poor. Members of the Federalist Party sent several delegations to the holder of the key vote to try to bribe him with various offers. Claiborne refused all of them, saying he thought it proper and honorable to obey the public voice on the matter.

The ballots began to be cast in eary 1801, and the states were equally divided on the first ballot; several other ballots took place, and the result was the same, when the House adjourned.

News of the tied vote spread like wildfire. The importance of Claiborne’s vote was so critical to the contest that when Congress began voting again, he went armed to the House, as no one could predict what violence might erupt. The public was barred from the proceedings as a safety precaution.

For several days and sometimes long into the nights, the votes were the same. All in all, a total of 36 ballots had been cast, with the same number of votes for Jefferson and Burr. On every vote, Claiborne had voted for Jefferson, and declared that he felt satisfied that Jefferson was the choice of the people, and that he intended to stick with that vote, no matter what the consequences.

On the last vote, the Vermont representative turned in a blank ballot, voting for no one, and Claiborne had the tie-breaking vote for Jefferson.

A native of Virginia born in 1775, Claiborne did not have the advantages of inherited wealth like some of his fellow Virginians in the late 1700s, but he made up for that by careful studies and through associations with benefactors who helped him attain important political positions while he was still a very young man.

He had attended Richmond Academy, and the College of William and Mary, then worked as a clerical assistant studying law in Congress at New York City, and then at Philadelphia. Among the prominent people at Philadelphia who noted Claiborne’s industriousness was Thomas Jefferson, who offered to lend him some books for his studies.

Claiborne returned to Richmond where he passed the bar, then at the request of his friend and later Tennessee governor General John Sevier, Claiborne moved to Sullivan County, Tennessee, where he soon was named one of the five members of the Tennessee delegation to form the newly-minted state’s constitution. Gov. Sevier made one of his first acts the appointment of Claiborne as a judge of the supreme court of law and equity of the state, citing his universally acknowledged merits despite the fact Claiborne had not quite turned 22 years old.

Even at that young age, Claiborne set his sights high, aiming to become district judge of Tennessee. He asked his influential friends in Virginia William Fleming and Edmund Randolph to recommend him to President George Washington for appointment in 1797. Fleming said in his letter to Washington that Claiborne’s “superior talents, great sobriety, and intense application to business distinguish him from the generality of young gentlemen of his age and should he be so fortunate as to succeed in his application, I am persuaded you will never have cause to regret the appointment.”

Claiborne did not get the district judge position as Tennessee Congressman Andrew Jackson told President Washington in his letter regarding the matter that “Mr. Claibourn (sic) is an amiable young Man, but perhaps not possessed of sufficient Experience to fill such an important office (district judge).”

Somewhat ironically, when Jackson vacated his representative seat to run for senator later in 1797, Claiborne successfully ran in the special election for Jackson’s former post in the House of Representatives, winning by a large majority over more seasoned and wealthier opponents. Only 22 years old, he was the youngest man who had ever appeared on the floor of Congress. He was re-elected to a full term in the House in 1798.

Jackson and Claiborne’s lives would intertwine more than a few times in subsequent years, and they never were on friendly terms. Jackson had been an enemy of Sevier, who was one of Claiborne’s mentors.

In 1803 at the transfer of Louisiana territory from France to the United States, President Jefferson furthered Claiborne’s prominence by naming him and General James Wilkinson to accept the transfer on the part of the US. From the outset, it was understood that Claiborne was tacit governor of the Territory of Orleans, and he moved from Natchez, Miss., to New Orleans.

In 1804, Jefferson officially appointed Claiborne governor of the Territory of Orleans, although he noted in his letter that Claiborne had not been his first choice for that honor. Jefferson had wanted his old friend, the Marquis de Lafayette, for the post, but Lafayette had turned him down. An earnest applicant for the governorship had been Andrew Jackson, who must have fumed that the young man he had considered inexperienced had won the job over him, in a large part due to that presidential vote.

When Louisiana became a state, in 1812, Claiborne had gained enough respect and admiration from the French and American citizens there that he easily became the first governor.

According to a biographical entry in “The National Portrait Gallergy of Distinguised Americans” when Louisiana was invaded by the British, Gov. Claiborne “voluntarily surrendered to General Jackson, when he arrived, the command of the militia of his state, and consented himself to receive his orders, a measure which he thought a just tribute to the military experience of General Jackson, and which he adopted, also, to avoid to his state all the expenses of the equipment and movements of her militia, which would have fallen upon her alone had he kept the command.”

Jackson made sure Claiborne and his select group of militia were nowhere near Chalmette, the main scene of the action which would culminate in the Battle of New Orleans on Jan. 8, 1815. On Dec. 23, 1814, Claiborne and his corps had received orders from Jackson to go to Gentilly to occupy the important pass of Chef Menteur as it was feared the British might try a diversion there. Claiborne and his group stayed there and fortified it, remaining at the spot through the whole contest and missing any action against the British.

Upon the expiration of his term as governor in 1817, Claiborne was elected to represent Louisiana in the Senate of the United States but before he could do so, he fell victim to liver disease on Nov 23, 1817, at the age of 42. He had lived a relatively brief life, but had left many legacies of his skill as both a statesman and patriot.

As a youth, Claiborne had written to President Washington that the “primary object of my life is to be useful to my Country,” and that “I shall labour to acquire the esteem of the present, and of after Ages for good and virtuous Actions.”

If Claiborne had been appointed district judge by Washington, he would not have been seated as a representative during the dramatic House vote of 1801. Burr, not Jefferson, may have won by a tie-breaking vote. The Louisiana Purchase may not have occurred. The Lewis and Clark Expedition would not have happened. Everything which evolved from Jefferson’s presidency would not have occurred, or would have happened differently. The value of one vote, and one man’s decision, in Claiborne’s case, was enormous.

Governor said on May 18, 2016

This is a very intriguing event in American history, and I enjoyed learning more about it from your article. I had not realized that Jackson even knew Claiborne personally prior to the Battle of New Orleans. As for who it was who really cast the deciding vote, it seems a rather difficult technical question. If the gentleman from Vermont doubly abstained from voting either for President or VP, then presumably the votes were tied once again. I suppose that if Claiborne was the last to cast his vote, and he abstained from voting for the VP while casting one vote for Jefferson, that is what put Jefferson one up over Burr. But it seems that even in such an event, it was the act of -not- voting for the VP which would have put Jefferson in as president, and not the act of voting for Jefferson per se. Because what seems to have led to the tie in the first place was that the Democratic-Republicans forgot to tell one of their members not to vote for a VP — and that’s how both Jefferson and Burr got the same number of votes.

Pam Keyes said on May 18, 2016

The details about what happened with the votes are quite complex, and not perfectly delineated anywhere in the archives. What is known for a surety is that Jefferson believed Claiborne cast the tie-breaker vote, and that he rewarded him accordingly. Jefferson gave no such favorable treatment to the representative from Vermont who cast the blank vote.